Source: HuffPost Canada Music | By Jason MacNeil

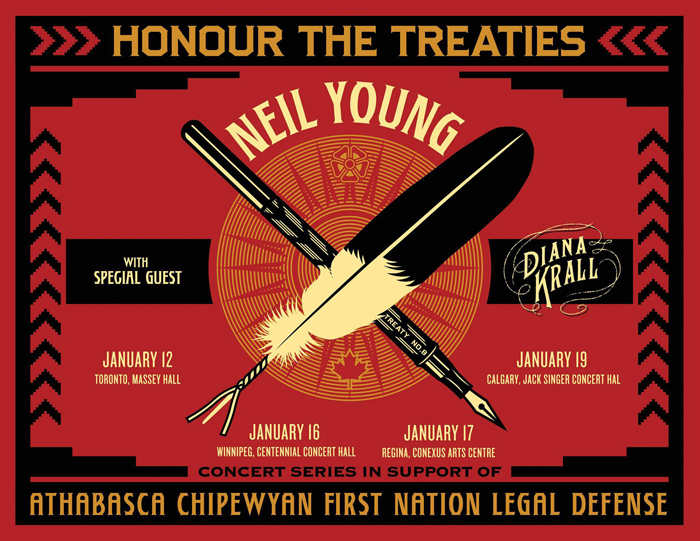

Neil Young has announced four intimate benefit shows as part of a week-long Canadian mini-tour dubbed “Honor The Treaties” to assist the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation (ACFN) Legal Defence Fund.

The four-city tour will include special guest Diana Krall as well and commences at Toronto’s Massey Hall on Jan. 12. Additional dates include Winnipeg’s Centennial Concert Hall (Jan. 16), Regina’s Conexus Arts Centre (Jan. 17) and concluding at Calgary’s Jack Singer Concert Hall on Jan. 19. Tickets for all four benefit gigs go on sale tomorrow (Dec. 10). Ticket prices have yet to be announced. The Canadian dates follow four scheduled concert Young has at New York City’s Carnegie Hall starting Jan. 6.

The ACFN “challenges against oil companies and government that are obstructing their traditional lands and rights.” The announcement adds the legal challenges will ensure “the protection of their traditional lands, eco-systems and unique rights guaranteed by Treaty 8, the last and largest of the nineteenth century land agreements made between First Nations and the Government of Canada, are upheld for the benefit of future generations.”

According to the ACFN’s page, the treaty was the last but largest agreement between the two parties, encompassing more than 840,000 square kilometers. “From that point in time up to the present, the federal government has claimed that the Cree, Dene, Metis and other various First Nations peoples living within the Treaty 8 boundaries had surrendered any claim to title to all but the lands set aside as reserves.”

The tour comes following Young’s description earlier this year of Fort McMurray and neighboring oilsands projects in Alberta, comparing Fort McMurray to “Hiroshima.” “People are sick,” he said during a speech in Washington, D.C. “People are dying of cancer because of this. All the First Nations people up there are threatened by this.”

Earlier in 2013, a series of Idle No More benefit concerts took place in various Canadian cities raising awareness about the issues facing First Nations. Guitarist Derk Miller organized such a gig in Ottawa in January, 2013 while other concerts took place from coast to coast.

Also in early January, 2013 dozens of Canadian musicians penned a letter supporting the Idle No More movement. According to a Facebook post, the letter demanded “Canadians honour and fulfill indigenous sovereignty, repair violations against land and water, and live the intent and spirit of our Treaty relationship.”

The letter was signed by artists such as John K. Samson, Gord Downie, Feist, Sarah Harmer, Steven Page, The Sadies, Justin Rutledge, Blue Rodeo’s Greg Keelor Jim Cuddy and Broken Social Scene’s Kevin Drew and Brendan Canning among others.

Although initial reports indicated tickets go on sale Tuesday (Dec. 10), a Ticketmaster link to the Winnipeg concert says tickets for that particular show go on sale Friday (Dec. 13). The link for the Winnipeg show also indicates the price range is from $59.50 on the low end up to $260.25 on the high end. Meanwhile, the Massey Hall link for the Toronto concert says tickets (ranging from $95 to $250) go on sale Friday morning at 10:30am local time.

Derrick on December 10th 2013

Derrick on December 10th 2013

A new venture, Enterprise Beverage Group LLC, has been established to produce, distribute and market the Hard Rock Energy drinks. The Seminole Tribe of Florida Inc. is the majority owner of Enterprise Beverage Group, which is based in Hollywood, Fla.

A new venture, Enterprise Beverage Group LLC, has been established to produce, distribute and market the Hard Rock Energy drinks. The Seminole Tribe of Florida Inc. is the majority owner of Enterprise Beverage Group, which is based in Hollywood, Fla.