The grassroots Idle No More movement was already planning a national day of action across Canada for January 28 to teach people about the First Nations Education Act, which most Indigenous Peoples oppose. Now the organizers are exhorting everyone to dress for the occasion—in a “Got Land? Thank an Indian” t-shirt or sweatshirt.

RELATED: First Nations Call Federal Education Act a Bust

Idle No More has scooped up 13-year-old Tenelle Starr, the eighth-grade student from Star Blanket First Nation who persuaded school officials to let her wear a hoodie with the words “Got Land?” on the front and “Thank an Indian” on the back.

RELATED: First Nation Student Wins Right to Wear ‘Got Land?’ Hoodie After School Ban

Since that day, the shirt’s maker in Canada, Jeff Menard, has been swamped with orders. But now he might want to add another phone line. Idle No More is calling on everyone across Canada to don the slogan, which Menard sells on t-shirts and bibs in all sizes, in addition to hooded and non-hooded sweatshirts.

RELATED: ‘Got Land?’ Hoodie Orders Flood in After School Controversy

Menard has set up a website, Thank An Indian, to field and fulfill orders. The shirts, bibs and other items that he said are forthcoming are also showcased on his Facebook page of the same name. A portion of the proceeds will go to help the homeless.

Those wishing to buy the slogan south of the 49th Parallel can order at its U.S. source. The White Earth Land Recovery Project, part of the Native Harvest product line that is run by Ojibwe activist and author Winona LaDuke, has sold hoodies and t-shirts bearing the slogan for years. Menard has said he got the idea after seeing friends from the U.S. wearing similar shirts.

The message and the lesson have taken on new urgency as racist comments proliferated on Tenelle’s Facebook page to such a degree that it had to be taken down. But that has only solidified the teen’s determination to make a difference and to educate Canadians, which she said was her intial goal in wearing the shirt to school.

She received support, too, from Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation in Alberta, which invited her to the Neil Young concert in support of its efforts to quell development in the oil sands of the province. She attended the Saturday January 18 performance as an honorary guest, according to Idle No More’s website. Young is doing a series of concerts to raise funds for the Athabasca Chipewyan’s legal fight against industrial activity in the sands.

RELATED: Neil Young: Blood of First Nations People Is on Canada’s Hands

Tenelle “is now calling, along with the Idle No More movement, for people everywhere to don the shirt as an act of truth-telling and protest,” Idle No More said in a statement on January 17. “Now and up to a January 28 Day of Action, Tenelle and Idle No More and Defenders of the Land are encouraging people across the country to make the shirt and wear them to their schools, workplaces, or neighborhoods to spark conversations about Canada’s true record on Indigenous rights.”

CBC News reported that Tenelle’s Facebook page was shut down at the suggestion of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), which briefly investigated some intensely negative and racist comments that were posted on the girl’s page after the school ruling.

“It was racist remarks with attempts to shadow it in opinion, but they were pretty forceful, pretty racist,” Sheldon Poitras, a member of the band council for the Star Blanket First Nation, and a friend of the family, said to CBC News. “The family was concerned about Tenelle’s safety.”

The family deactivated Tenelle’s Facebook account “on advice from RCMP,” CBC News reported, and the RCMP confirmed that it was investigating.

The message is a quip laden with historical accuracy that refers to the 1874 document known as Treaty 4, which Star Blanket First Nation is part of, in which 13 signatory nations of Saulteaux and Cree deeded the land to the settlers of what would become modern-day Canada.

Nevertheless, many continue to view the message as racist. Idle No More aims to debunk that notion as well as clarify the historical record. Tenelle has participated in Idle No More rallies with her mother as well, the group said.

“Everyone can wear the shirt,” said Tenelle in the Idle No More statement. “I think of it as a teaching tool that can help bring awareness to our treaty and land rights. The truth about Canada’s bad treatment of First Nations may make some people uncomfortable, but understanding it is the only way Canada will change and start respecting First Nations.”

Although Menard said that support has been streaming in from chiefs and others throughout Canada for both him and Tenelle, there has been negative feedback that shows there’s still a lot of misinformation to be dispelled, he told ICTMN.

“I’ve been getting hate messages, Tenelle has been getting hate messages,” Menard said in a phone interview on January 21, but reiterated that the slogan merely reflects historical fact. “If anybody learns their history they see that the Indians were here first.”

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/01/21/got-land-t-shirts-teach-ins-idle-no-more-calls-day-action-153185

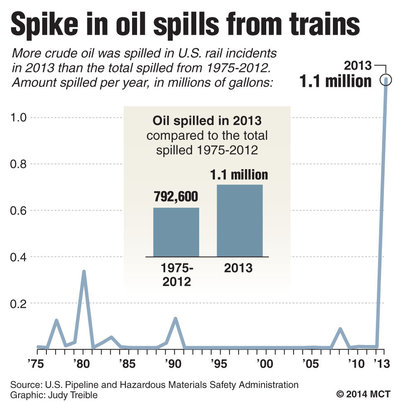

But until just a few years ago, railroads weren’t carrying crude oil in 80- to 100-car trains. In eight of the years between 1975 and 2009, railroads reported no spills of crude oil. In five of those years, they reported spills of one gallon or less.

But until just a few years ago, railroads weren’t carrying crude oil in 80- to 100-car trains. In eight of the years between 1975 and 2009, railroads reported no spills of crude oil. In five of those years, they reported spills of one gallon or less.