Crow & Lummi, Dirty Coal & Clean Fishing

“The tide is out and the table is set…” Justin Finklebonner gestures to the straits on the edge of the Lummi reservation. This is the place where the Lummi people have gathered their food for a millennium. It is a fragile and bountiful ecosystem, part of the Salish Sea, newly corrected in it’s naming by cartographers. When the tide goes out, the Lummi fishing people go to their boats—one of the largest fishing fleets in any Indigenous community. They feed their families, and they fish for their economy.

This is also the place where corporations fill their tankers and ships to travel into the Pacific and beyond. It is one of only a few deep water ports in the region, and there are plans to build a coal terminal here. That plan is being pushed by a few big corporations, and one Indian nation—the Crow Nation, which needs someplace to sell the coal it would like to mine, in a new deal with Cloud Peak Energy. The deal is a big one: 1.4 billion tons of coal to be sold overseas. There have been no new coal plants in the United States for 30 years, so Cloud Peak and the Crow hope to find their fortunes in China. The mine is called Big Metal, named after a Crow legendary hero.

The place they want to put a port for huge oil tankers and coal barges is called Cherry Point, or XweChiexen. It is sacred to the Lummi. There is a 3,500-year-old village site here. The Hereditary Chief of the Lummi Nation, tsilixw (Bill James), describes it as the “home of the Ancient Ones.” It was the first site in Washington State to be listed on the Washington Heritage Register.

Coal interests hope to construct North America’s largest coal export terminal on this “home of the Ancient Ones.” Once there, coal would be loaded onto some of the largest bulk carriers in the world to China. The Lummi nation is saying Kwel hoy’: We draw the line. The sacred must be protected.

So it is that the Crow Nation needs a friend among the Lummi and is having a hard time finding one. In the meantime, a 40-year old coal mining strategy is being challenged by Crow people, because culture is tied to land, and all of that may change if they starting mining for coal. And, the Crow tribal government is asked by some tribal members why renewable energy is not an option.

The stakes are high, and the choices made by sovereign Native nations will impact the future of not only two First Nations, but all of us.

How it Happens

It was a long time ago that the Crow People came from Spirit Lake. They emerged to the surface of this earth from deep in the waters. They emerged, known as the Hidatsa people, and lived for a millennia or more on the banks of the Missouri River. The most complex agriculture and trade system in the northern hemisphere, came from their creativity and their diligence. Hundreds of varieties of corn, pumpkins, squash, tobacco, berries—all gifts to a people. And then the buffalo—50 million or so—graced the region. The land was good, as was the life. Ecosystems, species and cultures collide and change. The horse transformed people and culture. And so it did for the Hidatsa and Crow people, the horse changed how the people were able to hunt—from buffalo jumps, from which carefully crafted hunt could provide food for months, to the quick and agile movement of a horse culture, the Crow transformed. They left their life on the Missouri, moving west to the Big Horn Mountains. They escaped some of what was to come to the Hidatsas, the plagues of smallpox and later the plagues of agricultural dams which flooded a people and a history- the Garrison project, but the Crow, if any, are adept at adaptation. The Absaalooka are the People of the big beaked black bird —that is how they got their name, the Crow. The River Crow and the Mountain Crow, all of them came to live in the Big Horns, made by the land, made by the horse, and made by the Creator.

A Good Country

“The Crow country is a good country. The Great Spirit has put it exactly in the right place; while you are in it you fare well; whenever you go out of it, whichever way you travel, you will fare worse… The Crow country is exactly in the right place.”

–Arapooish Crow leader, to Robert Campbell, Rocky Mountain Fur Company, c.1830

The Absaalooka were not born coal miners. That’s what happens when things are stolen from you—your land, reserved under treaty, more than 30 million acres of the best land in the northern plains, the heart of their territory. This is what happens with historic trauma, and your people and ancestors disappear – “1740 was the first contact with the Crow,” Sharon Peregoy, a Crow Senator in the Montana State legislature, explains. “It was estimated… to be 40,000 Crows, with a 100 million acres to defend. Then we had three bouts of smallpox, and by l900, we were greatly reduced to about l,750 Crows.”

“The 1825 Treaty allowed the settlers to pass through the territory.” The Crow were pragmatic. “We became an ally with the U.S. government. We did it as a political move, that’s for sure.” That didn’t work out. The 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty identified 38 million acres as reserved, while the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty greatly reduced the reservation to 8 million acres. A series of unilateral congressional acts further cut down the Crow land base, until only 2.3 million acres remained.

“The l920 Crow Act’s intent was to preserve Crow land to ensure Crow tribal allottees who were ranchers and farmers have the opportunity to utilize their land,” Peregoy explains.

Into the heart of this came the Yellowtail Dam. That project split the Crow people and remains, like other dams flooding Indigenous territories, a source of grief, for not only is the center of their ecosystem, but it benefits largely non-Native landowners and agricultural interests, many of whom farm Crow territory. And, the dam provides little financial returns for the tribe. The dam was a source of division, says Peregoy.“We were solid until the vote on the Yellowtail Dam in l959.”

In economic terms, essentially, the Crow are watching as their assets are taken to benefit others, and their ecology and economy decline. “Even the city of Billings was built on the grass of the Crows,“ Peregoy says.

Everything Broken Down

“Our people had an economy and we were prosperous in what we did. Then with the reservation, everything we had was broken down and we were forced into a welfare state.”

–Lane Simpson, Professor, Little Big Horn College

One could say the Crow know how to make lemonade out of lemons. They are renowned horse people and ranchers, and the individual landowners, whose land now makes up the vast majority of the reservation, have tried hard to continue that lifestyle. Because of history of land-loss, the Crow tribe owns some l0 percent of the reservation.

The Crow have a short history of coal strip mining—maybe 50 years. Not so long in Crow history, but a long time in an inefficient fossil fuel economy. Westmoreland Resource’s Absaloka mine opened in 1974. It produces about 6 million tons of coal a year and employs about 80 people. That deal is for around 17 cents a ton.

Westmoreland has been the Crow Nation’s most significant private partner for over 39 years, and the tribe has received almost 50 percent of its general operating income from this mine. Tribal members receive a per-capita payment from the royalties, which, in the hardship of a cash economy, pays many bills.

Then there is Colstrip, the power plant complex on the border of Crow—that produces around 2,800 mw of power for largely west coast utilities and also employs some Crows. Some 50 percent of the adult population is still listed as unemployed, and the Crow need an economy that will support their people and the generations ahead. It is possible that the Crow may have become cornered into an economic future which, it turns out, will affect far more than just them.

Enter Cloud Peak

In 2013, the Crow Nation signed an agreement with Cloud Peak to develop 1.4 billion tons in the Big Metal Mine, named after a legendary Crow. The company says it could take five years to develop a mine that would produce up to 10 million tons of coal annually, and other mines are possible in the leased areas. Cloud Peak has paid the tribe $3.75 million so far.

The Crow nation may earn copy0 million over those first five years. The Big Metal Mine, however may not be a big money-maker. Coal is not as lucrative as it once was, largely because it is a dirty fuel. According to the Energy Information Administration, l75 coal plants will be shut down in the next few years in the U.S.

So the target is China. Cloud Peak has pending agreements to ship more than 20 million tons of coal annually through two proposed ports on the West Coast.

Back to the Lummi

The Gateway Pacific Coal terminal would be the largest such terminal on Turtle Island’s west coast. This is what large means: an l,l00 acre terminal, moving up to 54 million metric tons of coal per year, using cargo ships up to l,000 feet long. Those ships would weigh maybe 250,000 tons and carry up to 500,000 gallons of oil. Each tanker would take up to six miles to stop.

All of that would cross Lummi shellfish areas, the most productive shellfish territory in the region. “It would significantly degrade an already fragile and vulnerable crab, herring and salmon fishery, dealing a devastating blow to the economy of the fisher community,” the tribe said in a statement.

The Lummi community has been outspoken in its opposition, and taken their concerns back to the Powder River basin, although not yet to the Crow Tribe. Jewell Praying Wolf James is a tribal leader and master carver of the Lummi Nation. “There’s gonna be a lot of mercury and arsenic blowing off those coal trains,” James says. “That is going to go into a lot of communities and all the rivers between here and the Powder River Basin.”

Is there a Way Out?

Is tribal sovereignty a carte blanche to do whatever you want? The Crow Tribe’s coal reserves are estimated at around 9 billion tons of coal. If all the Crow coal came onto the market and was sold and burned, according to a paper by Avery Old Coyote, it could produce an equivalent of 44.9 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide.

That’s a lot of carbon during a time of climate challenge.

Then there are the coal-fired power plants. They employ another 380 people, some of them Crow, and generating some 2,094 mw of electricity. The plants are the second largest coal generating facilities west of the Mississippi. PSE’s coal plant is the dirtiest coal-burning power plant in the Western states, and the eighth dirtiest nationwide. The amount of carbon pollution that spews from Colstrip’s smokestacks is almost equal to two eruptions at Mt. St. Helen’s every year.

Coal is dirty. That’s just the way it is. Coal plant operators are planning to retire 175 coal-fired generators, or 8.5 percent of the total coal-fired capacity in the U.S., according to the Energy Information Administration. A record number of generators were shut down in 2012. Massive energy development in PRB contributes more than 14 percent of the total U.S. carbon pollution, and the Powder River Basin is some of the largest reserves in the world. According to the United States Energy Information Administration, the world emits 32.5 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide each year. The Crow Tribe will effectively contribute more than a year and a half of the entire world’s production of carbon dioxide.

There, is, unfortunately, no bubble over China, so all that carbon will end up in the atmosphere.

The Crow Nation chairman, Darrin Old Coyote, says coal was a gift to his community that goes back to the tribe’s creation story. “Coal is life,” he says. “It feeds families and pays the bills…. [We] will continue to work with everyone and respect tribal treaty rights, sacred sights, and local concerns. However, I strongly feel that non-governmental organizations cannot and should not tell me to keep Crow coal in the ground. I was elected to provide basic services and jobs to my citizens and I will steadfastly and responsibly pursue Crow coal development to achieve my vision for the Crow people.”

In 2009, 1,133 people were employed by the coal industry in Montana. U.S. coal sales have been on the decline in recent years, and plans to export coal to Asia will prop up this industry a while longer. By contrast, Montana had 2,155 “green” jobs in 2007 – nearly twice as many as in the coal industry. Montana ranks fifth in the nation for wind-energy potential. Even China has been dramatically increasing its use of renewables and recently called for the closing of thousands of small coal mines by 2015. Perhaps most telling, Goldman Sachs recently stated that investment in coal infrastructure is “a risky bet and could create stranded assets.”

The Answer May Be Blowing in the Wind

The Crow nation has possibly l5,000-megawatts of wind power potential, or six times as much power as is presently being generated by Colstrip. Michaelynn Hawk and Peregoy have an idea: a wind project owned by Crow Tribal members that could help diversify Crow income. Michaelynn says “the price of coal has gone down. It’s not going to sustain us. We need to look as landowners at other economic development to sustain us as a tribe. Coal development was way before I was born. From the time I can remember, we got per capita from the mining of coal. Now that I’m older, and getting into my elder age, I feel that we need to start gearing towards green energy.”

Imagine there were buffalo, wind turbines and revenue from the Yellowtail Dam to feed the growing Crow community. What if the Crow replaced some of that 500 megawatts of Colstrip Power, with some of the l5,000 possible megawatts of power from wind energy? And then there is the dam on the Big Horn River. “We have the opportunity right now to take back the Yellowtail Dam,” Peragoy says. “Relicensing and lease negotiations will come up in two years for the Crow Tribe, and that represents a potentially significant source of income – $600 million. That’s for 20 years, $30 million a year.”

That would be better than dirty coal money for the Crow, for the Lummi, for all of us.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/01/15/crow-lummi-dirty-coal-clean-fishing-153086

Daybreak Star Cultural Center Faces Debt, Takes to Indiegogo

Source: Indian Country Today Media Network

The Daybreak Star Indian Cultural Center in Seattle, Washington is facing debt of $280,000 and has taken to the Internet for help.

“It is a really urgent situation. We really have to pay attention and get our bills paid for,” Jeff Smith, board chairman of the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation, which operates the facility, told KING 5 News.

Smith also said the center was going to close in September, but since then staff has been cut and the budget has been balanced. The center has six months to pay back half of the debt.

That’s why the nonprofit started an Indiegogo campaign to raise $25,000.

“We’re motivated to work really hard to raise money so it doesn’t go out of business,” Smith told KING 5 News.

“Not having Daybreak Star, not having United Indians would really negatively impact tens of thousands of people,” says Lynette Jordan, Colville/Ojibwe, family services director at the center, in the video on the Indiegogo page.

The center was built in 1974 and opened in 1977—seven years after about 100 Native Americans scaled the fence at what was then Fort Lawson. Those activists were ensuring Natives got a piece of the decommissioned Fort, which they did.

“They felt that we needed a place for the urban Indian population,” Chrissy Harris, Haida/Katzie, says in the video. She is administrative coordinator at the center.

The center provides a number of services to Natives in the Puget Sound area including giving elders a space to gather, providing foster care programs, outreach for urban Indians, programs for inmates, a youth home for homeless adolescents and a workforce program.

To help save Daybreak Star, visit Indiegogo. The center has until February to finish raising the money.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/01/13/daybreak-star-cultural-center-faces-debt-takes-indiegogo-153095

West Virginia Chemical Spill Ruins Water Supply for Thousands of Natives

American Indians were mobilizing this week to help more than 4,000 Natives who are among the 300,000 people without potable water in the wake of a January 9 chemical spill that rendered tap water undrinkable in several counties.

The no-use advisory was lifted on Tuesday January 14 for at least 100,000 of those affected, but problems remained.

“My sister has good water at their house, so they have been carrying water to those who don’t, making arrangements for water delivery to shut-ins and friends with disabilities and traveling extensively in the problem areas,” said Chief Wayne Gray Owl Appleton of the state-recognized Appalachian American Indians of West Virginia. As a senior chemist and emergency response specialist, he was among those working to resolve the issue.

The clear, colorless liquid known as 4-Methylcyclohexanol methanol seeped from a tank at Freedom Industries, which manufactures chemicals for the mining, steel and cement industries. The compound, which reportedly smells like black-licorice or cherry cough syrup, is a foaming agent used in the coal industry, according to CBS News. About 5,000 gallons of it escaped from a 40,000-gallon tank, state Department of Environmental Protection spokesman Tom Aluise said.

The affected members of the Appalachian American Indians of West Virginia live in all or parts of the counties of Kanawha, Boone, Cabell, Clay, Jackson, Lincoln, Logan, Putnam and Roane. State Department of Education spokeswoman Liza Cordeiro said schools in at least five of the counties would be closed.

A good 2,000 more indigenous people who belong to the 6,000-member Native American Indian Federation Inc. of Huntington, West Virginia, were also affected, said Chief David Cremeans.

Immediately after the spill, the federal government and the state of West Virginia declared nine counties as disaster areas, sparking a run on stores for bottled water. Shelves were stripped bare, and many West Virginians had no access to water. Residents who did not learn of the warnings in time and thus drank or bathed in the water suffered rashes and nausea. Others went to local with symptoms they said came from the water contamination.

Tension was palpable outside the contaminated area, with reports of price gouging and even fistfights.

“Nobody could find water,” said LaVerna Vickers, the tribal secretary of the Appalachian American Indians of West Virginia. “My husband and I looked to see if we were affected by the spill, and thankfully we live in Jackson County just outside of the West Virginia Water System Supply District.”

Vickers said it wasn’t until she got into the affected areas that she saw just how bad it was.

“We stopped outside of a store and a truck had already come and had cleared it out. We also heard from our friends that people were charging large amounts of money for water—people were selling five-gallon water bottles for one hundred dollars,” she said.

“Places like Wal-Mart weren’t putting the water on sale either. We couldn’t even find jugs to fill in the stores,” said Vickers. “You can also really feel the tension in Charleston. There have been fistfights and other altercations over water. Everyone is really tense.”

Vickers, who lives about 50 miles from the spill, said the past few days have been devastating. Further, she added, although officials said the spill occurred on Thursday, a reputable member of her community who lives just a few miles from the spill smelled the black licorice odor as early as Tuesday January 7. The effects were immediate, and visceral, Vickers said in describing the plight of a friend whom she was helping supply with water.

“I also have another friend who is deaf and lives a few miles from the spill,” Vickers said. “She had no water and couldn’t even go outside her door. When she tried to go outside she vomited.”

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/01/14/west-virginia-chemical-spill-ruins-water-supply-thousands-natives-153114

Snoqualmie Indian Tribe Announces Donations Focusing on Environmental Education

SNOQUALMIE, Wash., Jan. 15, 2014 /PRNewswire/ — The Snoqualmie Indian Tribe recently donated $15,000 to the Mercer Slough Education Center, run by the Pacific Science Center. “The partnership with the Snoqualmie Tribe helps us to provide memorable and exciting encounters with environmental science, reaching 10,000 students, parents, and teachers a year,” says Dana Fialdini. “The Pacific Science Center is grateful for the support we have received.”

Another recent donation of $25,000 to the Burke Museum is supporting the exhibit Elwha: A River Reborn, which focuses on the removal of the Elwha Dams. Julie Stein, Executive Director for the Burke, says the museum is “delighted to partner with the Snoqualmie Tribe” and that the sponsorship helps the Museum and others “celebrate and share the historic and transformational story with tens of thousands of people in our community, across the state, and far beyond.”

The Tribe also made donations to Sightline Institute and the Seattle Aquarium for $6,000 and $40,000, respectively. “We are honored to support these worthwhile organizations that focus on educating the community on important conservation and environmental matters,” said Tribal Secretary Alisa Burley.

These most recent donations are part of the Snoqualmie Indian Tribe’s long-standing commitment to investing in various nonprofit initiatives in the Snoqualmie area and statewide. Since 2010, the Tribe has donated over $3.5 million to hundreds of Washington State nonprofit organizations, including the Woodland Park Zoo, the Swedish Hospital, Seattle International Film Festival, Pike Place Market Foundation, and the Seattle Art Museum.

“We are truly humbled by the amazing work these local non-profits are doing in our communities and are proud to partner with them in their endeavors,” said Tribal Chairwoman Carolyn Lubenau. “We look forward to what the future may bring for the Tribe and its community partners.”

To qualify for a donation from the Snoqualmie Indian Tribe, an organization must be located within Washington State and a 501c3 non-profit organization. Applications are available online at www.snoqualmietribe.us with the next application cycle deadline set as Friday, January 31st.

The Snoqualmie Indian Tribe is a federally recognized tribe in the Puget Sound region of Washington State. Known as the People of the Moon, Snoqualmie Tribal members were signatories of the Treaty of Point Elliott with the Washington territory in 1855. The Tribe owns and operates the Snoqualmie Casino in Snoqualmie, WA.

Oregon Proposes Removing Hatchery Fish From Wild Fish Areas

By Cassandra Profita, OPB

Hatchery-reared fish would get the heave ho from certain rivers along the Oregon Coast under the latest strategy to help Oregon’s wild salmon and steelhead.

The new management plan proposed by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife would designate several coastal rivers as “wild fish emphasis areas,” while increasing the number of hatchery fish planted in other coastal rivers to expand fishing opportunities in those waters.

The idea is to improve the way six species of wild salmon and steelhead are managed without shortchanging those people who count on hatcheries to produce enough fish for them to catch.

To find the right balance, the agency convened several stakeholder committees with members from sportfishing, commercial fishing and conservation groups. Stakeholders spent months debating which rivers should get more hatchery fish and which ones should get less.

ODFW’s Coastal Multi-Species Conservation and Management Plan aims to conserve six species in 20 different river basins along the Oregon coast. None of the species are listed under the Endangered Species Act, and the state wants to make sure it stays that way.

The fish face threats from habitat loss, predators and overfishing. And also from their own hatchery-raised relatives. Studies show hatchery fish can compete with wild fish for habitat, and they can impact genetics through interbreeding. Several lawsuits are targeting hatcheries in the Northwest as scientists continue to document conservation risks to wild fish from hatchery releases.

Of course, hatcheries also serve an important role in coastal communities.

“They provide fish for people to catch,” ODFW program manager Tom Stahl says. “We’re trying to balance the hatchery program in terms of providing that fishing opportunity and also conserving wild fish populations.”

The state plan, which is currently in draft form and open to public comment, wouldn’t reduce the overall number of hatchery fish being released into coastal rivers. In fact, it would increase that number slightly from 6 million to 6.3 million per year. But it would reduce the number hatchery fish being released in some rivers such as the Kilchis, Siletz, and the Elk.

The plan has sparked outcry from both sportfishing and conservation groups. Some fishermen prefer to catch fish on rivers that would have fewer hatchery fish under the plan, and some conservation groups have put a lot of effort into improving wild fish runs on rivers that would get more hatchery fish.

After sitting on one of the committees, Alan Moore of the conservation group Trout Unlimited says it will be impossible to make everyone happy.

“The Kilchis River will be a wild fish emphasis area, and hatchery production will be moved to Nestucca River,” Moore says. “Trout Unlimited is planning a bunch of habitat conservation work on the Nestucca. We’re wondering: Should we be thinking about moving it to a different river where it stands a better chance of helping wild fish?”

Meanwhile, fishermen who rely hatcheries to ensure enough fish to catch are counting to make sure that the hatchery fish proposed to be removed from the Kilchis are actually going to be released somewhere else.

“Everybody’s counting fish,” Moore says.

The plan would also put more effort into preventing hatchery fish from interacting with wild fish overall, Stahl says, and it proposes a sliding scale for fishing seasons that would allow more fishing in years with higher predicted runs of fish.

“The plan really is trying to be proactive in increasing conservation as well as increasing fishing opportunity,” he says. “We’re threading that needle.”

ODFW is holding six meetings this month to collect public comments on the plan. The first meeting is from 6 to 9 pm Thursday at ODFW Headquarters, 4034 Fairview Industrial Drive SE, in Salem.

Other meetings will be held from 6 to 9 pm:

- Jan. 21 at the TIllamook County Library Meeting Room, 1716 3rd St., in Tillamook;

- Jan. 23 at the Best Western Plus Agate Beach Inn, 3019 N. Coast Highway, in Newport;

- Jan. 27 at Douglas County Library Meeting Room, 1409 NE Diamond Lake Blvd., in Roseburg;

- Jan 28 at North Bend Community Center, 2222 Broadway St., in North Bend; and

- Jan. 29 at Reedsport Community Center, 451 Winchester Ave., in Reedsport.

NW Native Art Show, July 19-20, 2014

The NW Native Art Show is now accepting vendor application, see here

Bill would clear convictions during 60s fish-ins

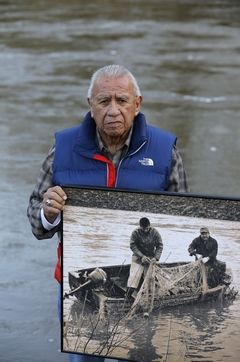

Billy Frank Jr., a Nisqually tribal elder who was arrested dozens of times while trying to assert his native fishing rights during the Fish Wars of the 1960s and ‘70s, holds a late-1960s photo of himself Monday (left) fishing with Don McCloud, near Frank’s Landing on the Nisqually River. Several state lawmakers are pushing to give people arrested during the Fish Wars a chance to expunge their convictions from the record.

By PHUONG LE, The Associated Press

SEATTLE — Decades after American Indians were arrested for exercising treaty-protected fishing rights during a nationally watched confrontation with authorities, a proposal in the state Legislature would give those who were jailed a chance to clear their convictions from the record.

Tribal members and others were roughed up, harassed and arrested while asserting their right to fish for salmon off-reservation under treaties signed with the federal government more than a century prior. The Northwest fish-ins, which were known as the “Fish Wars” and modeled after sit-ins of the civil rights movement, were part of larger demonstrations to assert American Indian rights nationwide.

The fishing acts, however, violated state regulations at the time, and prompted raids by police and state game wardens and clashes between Indian activists and police.

Demonstrations staged across the Northwest attracted national attention, and the fishing-rights cause was taken up by celebrities such as the actor Marlon Brando, who was arrested with others in 1964 for illegal fishing from an Indian canoe on the Puyallup River. Brando was later released.

“We as a state have a very dark past, and we need to own up to our mistakes,” said Rep. David Sawyer, D-Tacoma, prime sponsor of House Bill 2080. “We made a mistake, and we should allow people to live their lives without these criminal charges on their record.”

Lawmakers in the House Community Development, Housing and Tribal Affairs Committee are hearing public testimony on the bill Tuesday afternoon.

Sawyer said he’s not sure exactly how many people would be affected by the proposal. “Even if there’s a handful it’s worth doing,” he added.

Sawyer said he took up the proposal after hearing about a tribal member who couldn’t travel to Canada because of a fishing-related felony, and about another tribal grandparent who couldn’t adopt because of a similar conviction.

Under the measure, tribal members who were arrested before 1975 could apply to the sentencing court to expunge their misdemeanor, gross misdemeanor or felony convictions if they were exercising their treaty fishing rights. The court has the discretion to vacate the conviction, unless certain conditions apply, such as if the person was convicted for a violent crime or crime against a person, has new charges pending or other factors.

“It’s a start,” said Billy Frank Jr., a Nisqually tribal elder who figured prominently during the Fish Wars. He was arrested dozens of times. “I never kept count,” he said of his arrests.

Frank’s Landing, his family’s home along the Nisqually River north of Olympia, became a focal point for fish-ins. Frank and others continued to put their fishing nets in the river in defiance of state fishing regulations, even as game wardens watched on and cameras rolled. Documentary footage from that time shows game wardens pulling their boats to shore and confiscating nets.

One of the more dramatic raids of the time occurred on Sept. 9, 1970, when police used tear gas and clubs to arrest 60 protesters, including juveniles, who had set up an encampment that summer along the Puyallup River south of Seattle.

The demonstrations preceded the landmark federal court decision in 1974, when U.S. District Judge George Boldt reaffirmed tribal treaty rights to an equal share of harvestable catch of salmon and steelhead and established the state and tribes as co-managers of the resource. The U.S. Supreme Court later upheld the decision.

Hank Adams, a well-known longtime Indian activist who fought alongside Frank, said the bill doesn’t cover many convictions, which were civil contempt charges for violating an injunction brought against three tribes in a separate court case. He said he hoped those convictions could be included.

“We need to make certain those are covered,” said Adams, who was shot in the stomach while demonstrating and at one time spent 20 days in Thurston County Jail.

He also said he wanted to ensure that there was a process for convicted fishermen to clear their records posthumously, among other potential changes.

But Sid Mills, who was arrested during the Fish Wars, questioned the bill’s purpose.

“What good would it do to me who was arrested, sentenced and convicted? They’re trying to make themselves feel good,” he said.

“They call it fishing wars for a reason. We were fighting for our lives,” said Mills, who now lives in Yelm. “We were exercising our rights to survive as Indians and fish our traditional ways. And all of a sudden the state of Washington came down and (did) whatever they could short of shooting us.”

Governor to seek $200M more for schools

By Jerry Cornfield, The Herald

OLYMPIA – Gov. Jay Inslee surprised lawmakers Tuesday with a call to give public schools $200 million in new funding, with a portion earmarked for the first cost-of-living increase for teachers in five years.

Inslee, who’s been saying he would seek a major investment in education, changed course after the state Supreme Court recently scolded lawmakers for moving too slowly to fully fund basic education as required by the state constitution.

“Promises don’t educate our children. Promises don’t build our economy and promises don’t satisfy our constitutional and moral obligations,” Inslee said in prepared remarks to a joint session of both chambers of the Legislature.

“We need to stop downplaying the significance of this court action. Education is the one paramount duty inscribed in our constitution,” Inslee said during his noontime State of the State Address.

Also Tuesday, Inslee pressed lawmakers to pass a transportation package and increase the state’s minimum wage by as much as $2.50 an hour. Today the minimum wage in Washington is $9.32 per hour.

Regarding education funding, the first-term Democratic governor will propose closing tax breaks to generate the revenue, a change he sought without much success last year. He didn’t spell out which tax breaks he will seek to close.

“You can expect that again I will bring forward tax exemptions that I think fall short when weighed against the needs of our schools,” according to the remarks provided in advance of his speech.

On transportation, Inslee urged lawmakers to find common ground in time to reach agreement before this year’s 60-day session ends in March. The House is controlled by Democrats and the Senate is controlled by Republicans.

“If education is the heart of our economy, then transportation is the backbone. That’s why we need a transportation investment package,” he said. “The goal cannot be for everyone to get everything they want. Instead, we must get agreement on what our state needs.”

And he said he wasn’t sure how much the minimum wage should climb but knows it needs to be higher than it is today.

“I don’t have the exact number today for what our minimum wage should be. It won’t be a number that remedies 50 years of income inequality,” he said. “But I believe that an increase in the range of $1.50 to $2.50 an hour is a step toward closing the widening economic gap.”

The governor also called for reform that would ensure businesses pay no business-and-occupation tax if they earn less than $50,000 in revenue in a year.

Houser sculptures to be installed at Okla. Capitol

By Sean Murphy, Associated Press

OKLAHOMA CITY — Statues, paintings and other artwork by the late Chiricahua Apache artist Allan Houser will be on display across the state this year to honor the 100th year of his birth, including five monumental-sized sculptures that are being installed at the state Capitol this week.

Installation of the five bronze statues will begin Wednesday at the Capitol’s east entrance, where two large sculptures entitled “Morning Prayer” and “Singing Heart” will be erected. Two more will be installed at the west entrance, along with a fifth piece that will be placed on the north plaza. All five will be on display through December.

Additional Houser exhibits are planned throughout 2014 in Duncan, Norman, Oklahoma City, Stillwater and Tulsa.

Houser, who died in 1994, was a renowned Native American artist and among the most influential of the 20th century. Oklahoma’s license plate depicts Houser’s “Sacred Rain Arrow” and his sculptures greet visitors to the Oklahoma Capitol, the University of Oklahoma in Norman and the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa.

Born to Apache parents who were brought to Fort Sill as prisoners of war, Houser, born Allan Haozous, was symbolic of the first generation of American Indians forced to make a transition into the white culture, said Bob Blackburn, director of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

“He changed Indian art in America,” Blackburn said. “He’s the pivot point from advocating Indian art as a way to make a living to an expression of their own imagination and observations.

“He really gives many Indian artists their ability to express themselves in their own individual way.”

Houser’s nephew, Jeff Haozous, the chairman of the Fort Sill Apache Tribe, said his uncle was a talented and productive artist who also spent decades teaching art to younger generations of artists.

“He’s an inspiration based on what he was able to achieve,” Haozous said. “As a nephew and a tribal member, it’s something I’m really proud to see his art getting such recognition.”

Haozous said 2014 is significant for the tribe because it marks the centennial of the tribe’s freedom following the imprisonment of its members, who were among the last to engage in battles with the U.S. Army.

“They had been living on Fort Sill as POWs, and now they were free Apaches,” Haozous said. “That is of huge significance to us, and as a tribal leader, that is the most significant thing to happen this year.”

—

Online:

Allan Houser: Oklahoma perspective: www.okhouser.org