The thing I like about state of unions – the national kind, the NCAI kind, and the tribal kind – is that it’s a to do list. Leaders see this as a list of “action items” while I see this as a list of fascinating issues that are worth exploring in future columns.

I want to start with an idea raised by President Barack Obama in his State of the Union message: “Let’s make this a year of action. That’s what most Americans want – for all of us in this chamber to focus on their lives, their hopes, their aspirations.”

What would a “year of action” look like in Indian country? And, more important, how do we get there?

National Congress of American Indians President Brian Cladoosby began this year’s State of Indian Nations by talking about so many of the success stories from Indian country. “Tribal leaders and advocates have never been more optimistic about the future of Native people,” he said. But that sense of possibility is “threatened by the federal government’s ability to deliver its promises.”

President Cladoosby released NCAI’s budget request for the coming fiscal year. That document calls for funding treaty obligations with the “fundamental goal” of parity for Indian country with “similarly situated governments.” As a moral case, and cause, this is exactly right. This is an aspirational document, as it should be.

But in a year of action there needs to be another route forward. This Congress is incapable of honoring treaties. Even in a more friendly era, members of Congress proudly called Indian health a “treaty right” only to appropriate less than what was required. This year’s federal budget essentially is flat (which means less program dollars because Indian country’s population is growing). NCAI puts it this way: “However, the trend in funding for Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior does not reflect Indian self-determination as a priority in the federal budget.”

But it’s not the Interior Department. It’s all of government and especially the Congress.

To my way of thinking, this particular moment in history is especially important. The demographics of Indian country – a young, growing population – exactly matches the greater need of the nation as a whole (a nation that is rapidly aging). Cladoosby said in the past 30 years the number of American Indian and Alaska Natives in college has more than double.

Cladoosby, who is chairman of the Swinomish Indian Community, said that his tribe is providing scholarships for their young people to the colleges of their choice. That’s smart. I wish more tribes could afford that approach. But there are other ways that this can happen, too.

So here is one idea: What if President Obama, when he visits Indian country this year, partners with tribal leaders to raise private money for tribal colleges? How much is possible, a new billion dollar endowment? Why not?

Or what about expanding efforts to forgive student debt? Too many young Native Americans are burdened by loans. If tribal members choose to be teachers or serve tribal governments, erase what they owe. (And expand similar programs for young people who choose health care careers.)

Two other items in the State of Indian Nations that are important and exciting are tribes building international partnerships, President Cladoosby mentioned Turkey, as well as tax reform so that tribes can raise their own funds. He said tribes should get at least the same tax treatment as states. This could be new money. Action dollars.

In a year of action, it seems to me, the most lucrative funding routes do not involve Congress or appropriations.

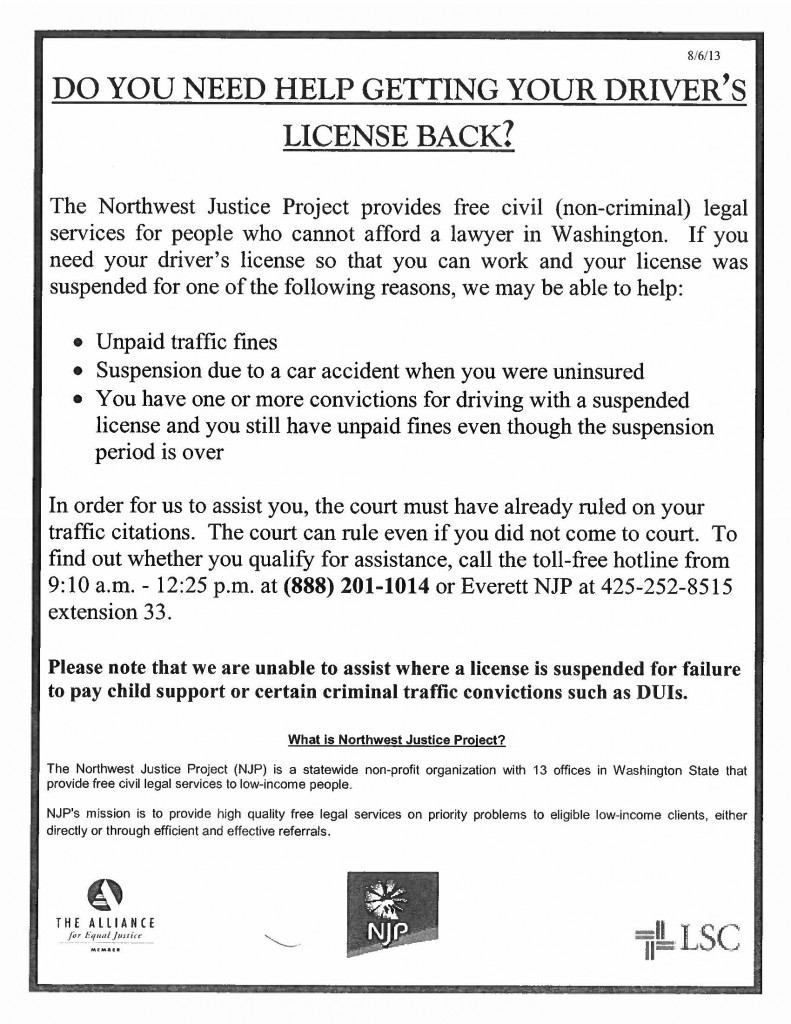

In his congressional response, Montana Sen. Jon Tester hit on a couple of billion dollars just waiting to be picked up, and that’s the Affordable Care Act. Congress is not going to fully fund Indian Health Service. But that full-funding could happen if every eligible American Indian and Alaska Native signed up for tribal insurance, Medicaid, or purchased a free or subsidized policy through an exchange. This is money that Congress does not have to appropriate.

A couple billion dollars? Just waiting for a year of action.

Mark Trahant is the 20th Atwood Chair at the University of Alaska Anchorage. He is a journalist, speaker and Twitter poet and is a member of The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes. Comment on Facebook at: www.facebook.com/TrahantReports.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/01/30/year-action-indian-country-153346