By Kalvin Valdillez, Tulalip News

“At this time, we remember and acknowledge our ancestors who signed the treaty,” said Tulalip Elder, Inez Bill. “We reflect on the importance of that treaty – who we are as a people and how to continue our way of life – a commemoration of the signing of the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott that affected the coastal tribes.”

January 22nd marks 167 years since tribal leaders across the northern Puget Sound region gathered at the location that is presently known as Mukilteo. A historic day in which representatives from various tribes, bands and villages, including the people of Snohomish, Lummi, Swinomish and Suquamish, met with Washington Territory Governor Issac Stevens to negotiate and sign a document that would become known as the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott. Close to 5,000 Coast Salish people were in attendance, and the negations required two translators – one translating English to Chinook Jargon and the other interpreter translated the Chinook Jargon into the traditional languages of the various tribes.

“We honor the good intentions our ancestors had for us in negotiating and signing the treaty,” stated Lena Jones, Tulalip Elder and Education Curator of the Hibulb Cultural Center. “I encourage young folks to listen to their elders when they talk about the treaty and our sovereignty. Understanding the treaty will help you understand the influence it has in every aspect of our lifeways.”

With their future generations in mind, the tribal leaders ceded upwards of 5 million acres of ancestral land to the United States government for white settlement. Today, that enormous amount of land currently makes up Washington’s King, Snohomish, Skagit and Whatcom counties. The treaty established the Tulalip, Port Madison, Swinomish and Lummi reservations, and thereby acknowledged each tribe as a sovereign nation. In exchange for ceding such large portions of land, the tribes reserved the right to fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations, as well as the right to hunt and gather on open and unclaimed lands.

“Treaty rights are an inherent right,” explained Ryan Miller, Tulalip Tribes Director of Treaty Rights and Governmental Affairs. “Treaty rights were not given to tribes. It’s a common misconception that the government gives Native Peoples special rights. That’s the exact opposite of how it works. Tribes are sovereign nations, they give up rights and they retain rights. Treaty rights are rights that are not given up by tribes, and they’re upheld by the federal government as part of their trust relationship with the treaty tribes. The tribes’ right to self-govern is the supreme law of the land. It’s woven into the U.S. constitution as well as many legal decisions and legislative articles. The constitution says Congress has the power to make treaties with sovereign nations, and that treaties are the supreme law of the land.”

Tulalip Fisherman, Brian Green, expressed, “The treaty is literally my livelihood. We fight for our rights every day – fighting to keep our treaty rights. I want my kid’s kids to come out here and be able to exercise their treaty rights. Not everyone has to be a fisherman, but it should be there if they want to exercise it.”

Tribal communities faced difficult years after the signing of the treaty, including the boarding school era. Fifty years after the signing of the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott, the Tulalip Indian Boarding School opened, one of many Indian boarding schools throughout the country. During this dark era of American history, Native children were forcibly removed from their families and had to attend these schools and learn how to live the new colonized lifestyle.

The institutions were established to ‘civilize’ the Indigenous population. But while at these boarding schools, the kids were often punished, physically and mentally, for speaking their traditional language and practicing their spiritual and cultural teachings. Many children died as a result of the abuse, while the ones who made it through these atrocities often, and unknowingly, passed on their traumas to the next generations, causing vicious cycles of abuse and destructive coping mechanisms to deal with that abuse, throughout the years.

During this era, the U.S. Government also outlawed traditional practices and spiritual ceremonies that took place on these lands since time immemorial. Coast Salish tribal members could not sing their songs, perform their dances or speak their ancestral languages, and therefore could not pass those teachings to the next generations. Longhouses were demolished and modern-day houses were erected on the reservations. The people who inhabited, lived-off and cared for this land for ages were to learn the ways of agriculture and become farmers.

The descendants of the signatories of the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott were in the middle of experiencing the horrors of forced assimilation when the last hereditary chief of the Snohomish, William Shelton, stepped in to save his people’s heritage, culture and way of life. In 1912, persistence paid off when he convinced the Tulalip Superintendent and the U.S. Secretary of Interior to build a longhouse along the shores of Tulalip Bay.

William created a way for the tribes to practice their traditional lifeways every winter by informing U.S. Government officials that the people would be celebrating and commemorating the anniversary of the treaty once a year at the longhouse. This allowed tribal elders and wisdom keepers the opportunity to teach the younger generations about their culture, which seemed to be slipping away at an alarming rate due to colonized efforts. The annual gathering became known as Treaty Days, a yearly potlatch that often extends into the early morning of the following day.

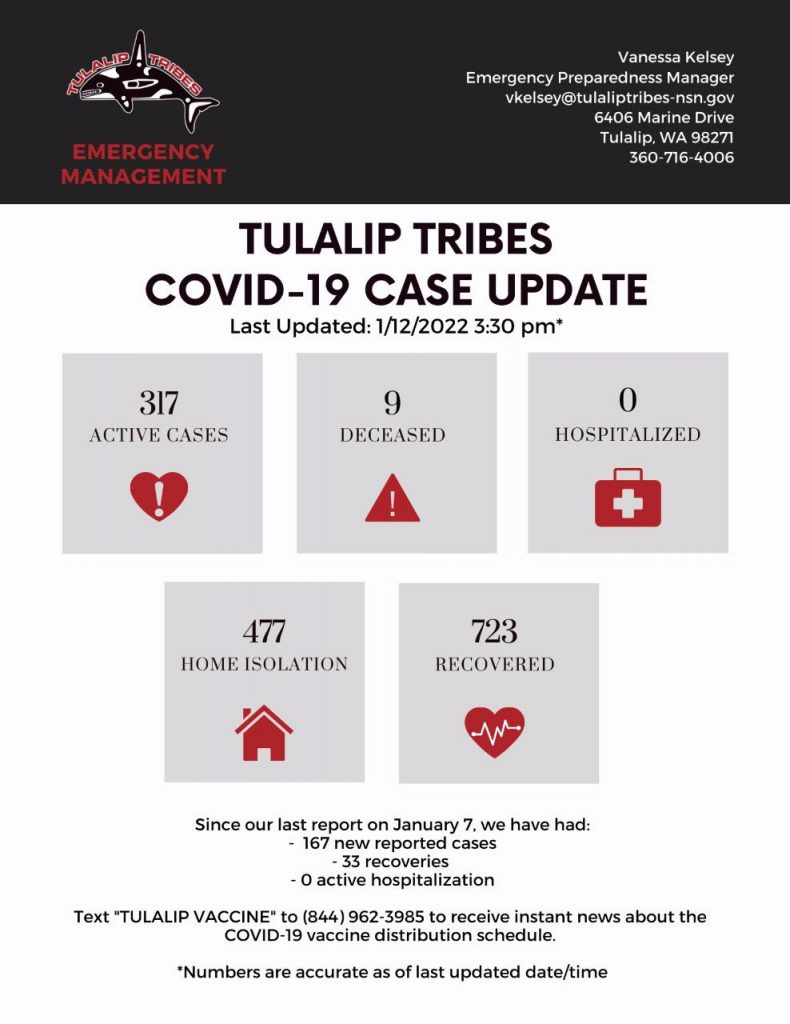

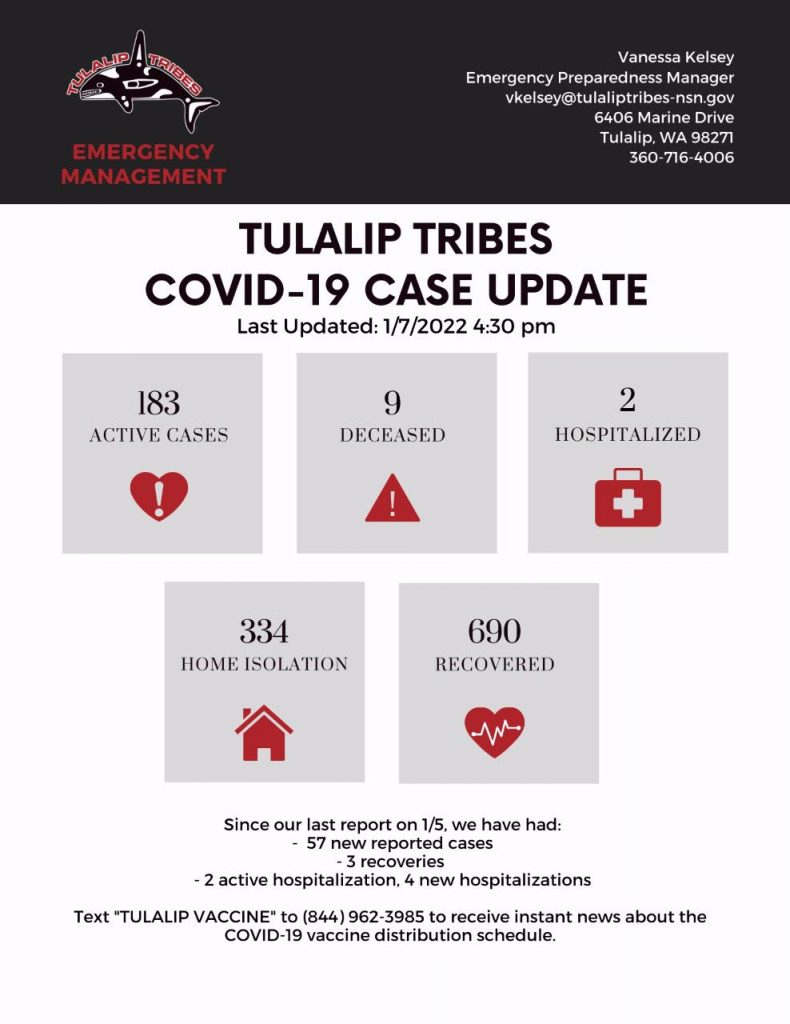

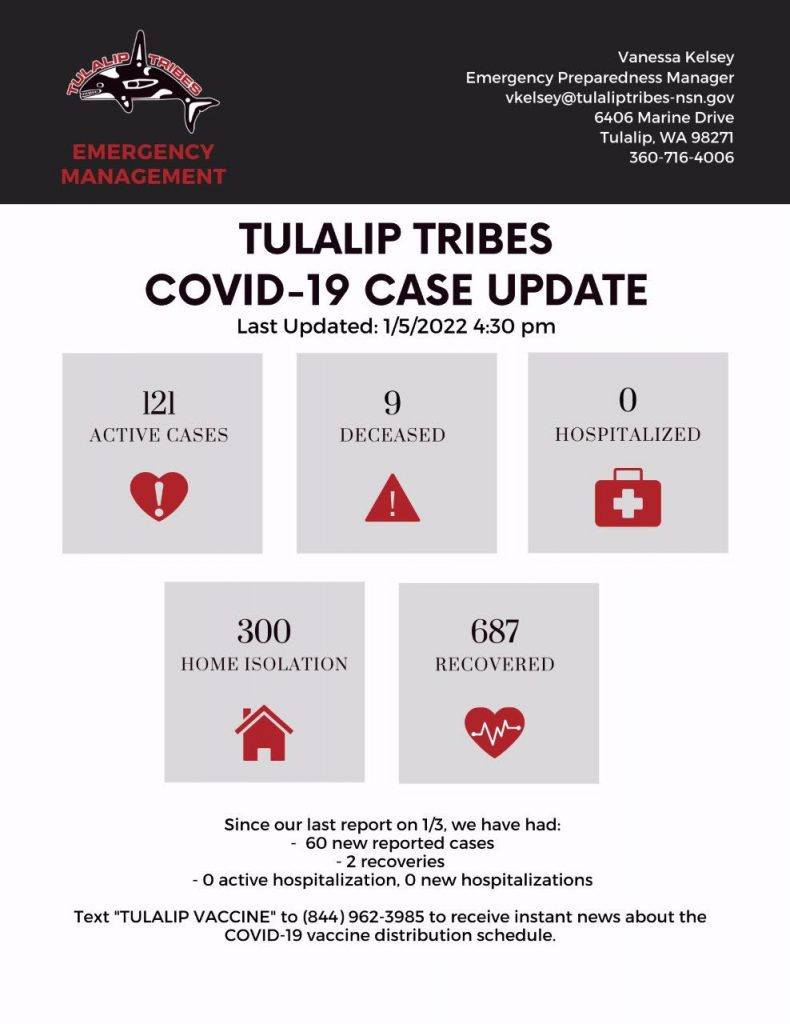

Treaty Days is an event that tribal members across the region look forward to every year. Although the original longhouse, which Shelton convinced the government to build, was replaced in the sixties, people met at the historical location every January 22nd for over 100 years after the first Treaty Days ceremony took place. Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, tribal members have not been able to gather to commemorate the treaty for the past three years. However, many tribal families still take the time to honor, reflect, study and pass on the knowledge of the treaty to the next generations at home, until it is safe to convene once more in large numbers at the smokehouse.

“I think that we have the responsibility to revisit the treaty all the time, so we know we are keeping our younger people abreast and informed as much as possible,” said Ray Fryberg, Tulalip Elder and Hibulb Cultural Center Tribal Research Historian. “We gave up a lot in the treaty to keep our sovereignty – to be able to determine our own future and our own direction in our tribal path. And also just living on the reservation, and protecting those rights that were reserved for us, as well as the spiritual and cultural way of life.”

Added Lena, “The treaty accepts the fact that our people have the right to organize themselves, protect our way of life, and care for our resources. Our tribes have significant control of, and rights to, important natural resources such as fishing. As our language and culture become stronger, we are able to help others understand how to take care of the earth and one another.”

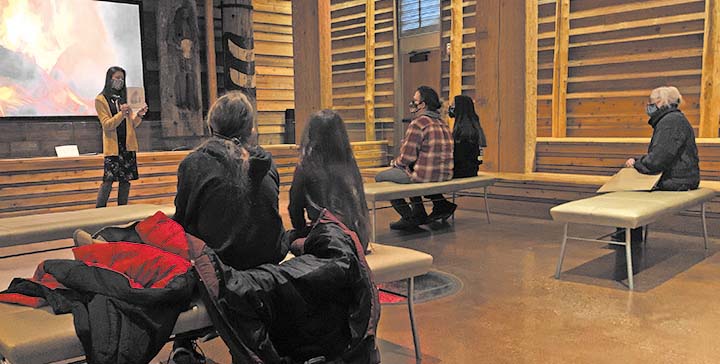

The 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott is currently on display at the Hibulb Cultural Center as a part of their The Power of Words: A History of Tulalip Literacy exhibit. For more information, including the most up-to-date COVID guidelines and restrictions, please contact the museum at (360) 716-2600 or visit the Hibulb Cultural Center’s Facebook page.