Tribal Leaders Meet with Vice President Biden who Addresses Efforts to End Violence Against Women Attorney General Holder Announces Initiative on Indian Child Welfare Act

syəcəb

By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

The Tulalip Lady Hawks (0-5) hosted the Orcas Christian Saints (2-1) on December 16, 2014. Coming off a narrow defeat to archrival Lummi in a previous game, the Lady Hawks were looking to rebound with their first win of the season.

Coach Cyrus “Bubba” Fryberg and his Lady Hawks would have their work cut out for them as they would be playing with only 5 eligible players, meaning no bench and no substitutions for the already thin roster.

The 1st quarter got off to a rough start for the Lady Hawks as the Orcas Christian Saints played a full court press defensively the first several possessions that resulted in consecutive turnovers by the home team. To make matters worse, the Lady Hawks looked slow and lethargic while not hustling to rebounds. Because of the lack of energy the Saints collected 5 offensive rebounds on one possession. With 3:00 remaining in the opening quarter the Lady Hawks found there hustle and looked like they were ready to play for real. There was an offensive focus to get the ball to the Lady Hawk bigs Nina Fryberg and Jaylin Rivera. Both were able to get into good offensive position and get off clean shots, but they didn’t fall. The 1st quarter ended with the Lady Hawks trailing 0-11.

Following the lackluster 1st quarter showing, Coach Fryberg urged his players to push the tempo offensively and for the guards, Michelle Iukes and Myrna Redleaf, to be more aggressive while looking for their shots. After giving up a quick bucket to go down 0-13, the Lady Hawks buckled in defensively to force back-to-back turnovers. Michelle Iukes showed her coach the aggression he was looking for by pulling down an offensive board and getting fouled on the put-back attempt. Michelle went one for two at the free throw line to put the Lady Hawks on the board 1-13. On the very next possession Myrna found a wide open Michelle who swished in a 3-pointer. Moments later Myrna forced a Saints turnover and Coach Fryberg called a timeout. He drew up a play that was executed to perfection and resulted in Michelle hitting another 3-pointer. The Lady Hawks were on a 7-0 run and brought the score to 7-13. The Saints responded by hitting a 3-pointer of their own, followed by a Nina Fryberg free throw and a baseline jumper by Michelle. With the score now 10-16 the Saints called a timeout.

Coming out of their timeout, the Saints ran a defense that this basketball enthusiast hadn’t seen before. Later I learned it was called the diamond press or 1-2-1-1 full court press. It’s a trapping man-to-man defense that only works if you have quick guards who can “heat up the ball” in a one-on-one situation. This means getting the ball handler out of control and blinding him from the impending trap, which comes from a secondary defender who’s lurking near half-court. For the remainder of the 2nd quarter, the Saints remained in their diamond press defense and the Lady Hawks committed eight turnovers while not scoring another point. At halftime the Lady Hawks trailed 10-24.

The Saints’ diamond press defense continued to stifle the Lady Hawks in the 3rd quarter. Following back to back turnovers, Myrna found an open Michelle who shot and made her third 3-pointer of the game to make the score 13-26. Over the remainder of the 3rd quarter the Lady Hawks would only score two more points, scored by Jaylin Rivera, as the Saints defense continued to slow down the visibly frustrated Lady Hawks. Meanwhile the Saints were getting easy buckets off of 14 forced turnovers. Going into the 4th quarter the Lady Hawks trailed 15-41.

After getting the short break to rest before the start of the 4th quarter the Lady Hawks came out hustling. They were running back on defense and not letting the Saints take uncontested shots. On offense the shots weren’t following until Michelle inbounded to an open Jaylen who made an elbow jumper to make the score 17-41. Unfortunately for the Lady Hawks that would be their last basket of the game as Jaylin soon after fouled out. Having no bench players for this game meant the Lady Hawks would play the rest of the game 4-on-5. This added challenge made it difficult to get any offense going. The game ended 17-49 in favor of the Orcas Christian Saints.

Following the game Lady Hawk Michelle Iukes was very upbeat about the team’s development. “We’ve gotten a lot better at beating the press. We didn’t panic or anything. But we have to look middle more because they [Jaylin and Nina] are open. I think everyone has improved and we are able to look inside more, down low more and not just high post.”

The Lady Hawks remain positive and are determined to get their first win on the season in the coming weeks.

Micheal Rios, mrios@tulaliptribes-nsn.gov

By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

The 2-1 Heritage Hawks hosted the 1-2 Orcas Christian Saints on December 16, 2014. The Hawks were looking to rebound from their first loss of the season, falling to Lummi Nation 55-79. Senior guard Ayrik Miranda was making his home debut vs the Saints and inserted into the starting lineup.

The 1st quarter got off to a rocky start as the Hawks failed to connect on their first four shots, while the Saints started off 3-3 from the field to take an early 7-0 lead. Two minutes into the opening quarter Center Robert Miles was fouled while shooting and subsequently made a free throw to put the Hawks on the board, 1-7. The Saints responded by converting two free throws of their own to take a 9-1 lead. That would be the largest lead of the game by the Saints as the Hawks got their offense going. The Hawks spread the floor offensively and focused on moving the ball from player to player. Over the next 3:00 of game play the Hawks stellar ball movement resulted in an 8-0 run to tie the game at 9-9. The Saints responded with a 7-0 run of their own, taking advantage of offensive rebounds on four straight possessions, to take a 16-9 lead. In the Hawks closed the quarter on a 4-0, scoring two straight transition buckets. At the end of 1 the Hawks trailed 13-16.

The Hawks carried their momentum into the 2nd quarter by scoring two quick buckets to take their first lead of the game, 17-16. Making his home debut in fashion, Ayrik was in the midst of scoring 10 straight Hawk points. Both teams traded baskets until the Hawks called a timeout with 5:16 remaining in the half, with the Hawks trailing 24-25. Ayrik and Trevor Fryberg hit back-to-back 3-pointers and Willy Enick hit an elbow jumper to put the Hawks up 31-29, leading to a Saints’ timeout. Following the timeout Aryik hit another 3-pointer to give the Hawks their largest lead of the game, 34-29. To this point Ayrik was on fire having scored 14 points in the quarter and 18 of the last 25 points scored by the Hawks. The initial defense of Hawks was forcing the Saints to take contested jumpers, but because the Hawks weren’t boxing out the Saints’ bigs were getting easy putback baskets. The offense continued to flow regardless, and Jesse Louie found his range hitting a 3-pointer and Willy Enick hit an elbow jumper to extend the Hawks lead to 44-36 at halftime.

Coach Cyrus “Bubba” Fryberg used the halftime intermission to motivate his Hawk players to improve their defense play. “Defensively we are being outhustled. They have gotten way too many rebounds and they are scrapping to go get the ball. Why? Because we are playing lazy. We have to play harder, box out more, and hustle after the ball,” Fryberg told his players.

With the defensive intensity turned up, the Hawks came up with two steals during a 7-0 run to open the 2nd half to push their lead to 51-36. Both teams would alternate scoring baskets over the next several minutes, all the while the Hawks maintaining a double digit lead. That is until they committed four turnovers in the final 1:30 of the 3rd quarter. The turnovers proved costly as the Saints converted them into buckets, closing the quarter on a 6-2 run. Going into the final quarter the Hawks lead was down to 8 points, 59-51.

The Hawks began the 4th quarter with the same defensive mindset their coach instilled in them at halftime. They forced six straight Saints turnovers to hold the Saints scoreless three minutes into the final quarter. Capitalizing on their defense and getting timely offensive rebounds and putback layups by Enick the Hawks were on a 6-0 that pushed their lead to 65-51 with 5:06 left to play. Seeing enough of his team committing turnovers the Saints coach called a timeout to have his team regroup. Following the timeout the Saints put their offense in the hands of their point guard Michael Harris. He drove to the basket aggressively on the next six Saints possessions, scoring two buckets and coming away with four made free throws. On the other end, the Hawks continued to move the ball well and were scoring at the rim. With 3:00 to go the Hawks led 70-59. Saints’ Michael Harris again drove to the rim scoring another bucket; he had scored the last 10 Saints’ points. The Hawks continued to score off their offense sets and adjusted defensively by packing the paint to stop the Saints’ point guard from driving to the hoop. When the game was over the Hawks were now 4-1 on the season as they beat the Saints 76-63.

Micheal Rios, mrios@tulaliptribes-nsn.gov

by Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

When you think of the holiday season, what do you think of? Is it time off from work? Is it family? Or is it about the gifts you still have to buy? For most of us it’s probably a combination of those answers, with the emphasis on the stuff you still have to buy. Our holiday season has become overshadowed by the materialism and appetite for consumerism that invades modern times. Not only are we buying stuff to give to people, buying holiday foods to eat, but we are also buying stuff to decorate our houses. For those who attended the 3rd annual Wreath Making Class, offered at the Tulalip Hibulb Cultural Center on December 10, they were able to celebrate the holiday season the traditional way; honoring the cause by creating a holiday wreath with family and friends that they chose to enjoy their time with.

In its third year, the wreath making event was coordinated by Inez Bill, Rediscovery Coordinator for the Hibulb Culture Center, Joy Lacy, Historic Records Curator, and Virginia Jones, Cultural Resources Secretary. They harvested resources such as cedar boughs, salal plants, holly, and ferns from the Tulalip woods that were used to make the holiday wreaths. Of having to go into the woods to harvest Joy Lacy said, “You forget about the little things in life until you get out in the woods and start gathering. It felt good being out in the woods. When you get back there you know what you are missing.”

Attendees of this year’s wreath making class were treated to a festive, communal gathering of Tulalip tribal members, tribal employees, and invited guests who came together with the common purpose of hand making a holiday wreath. “It’s my way of giving to the people. It’s an opportunity for people to make something, enjoy themselves, and to have something they’ve made by hand,” Inez Bill says of the wreath making class.

There was a variety of supplies on hand, so that each person could make their own unique wreath while creating connections with those around them. Even the creative novice would not have difficulty creating something to be proud of, as there was plenty of help and ideas to be offered by the event coordinators. The experience of creating something by hand, in such a welcoming, cheerful environment, makes the end result of having a wreath to giveaway as a gift or hang as a decoration so much more meaningful, something one simply can’t purchase from a retail store.

Among the attendees were three University of Washington students from the international and prestigious Restoration Ecology Network. They came to experience the ethnobotanical influence that the local environment has on traditional Tulalip activities. Inez Bill described the ethnobotancial influence of the wreath making class as being one of healing and keeping our connection to nature thriving.

“To me, I think anything you do working with your hands can be healing. Here, at Hibulb Cultural Center, we follow the teaching and values when we harvest anything. We only take what we need. We move area to area while harvesting. That way we aren’t wiping out one area. We value those traditional values and teachings. I think a lot of the plants that we harvest have medicinal values and other uses but at this time we are using them for wreaths. Cedar boughs have always been important to our people. You can brush yourself off with it. Some of the other plants, like salal, we use the berries from it. These plants we are familiar with. To go into nature and harvest them and have them here, we are hoping to keep that connection with nature in doing events like this for our people.”

Also in attendance were five members of the local Tulalip movement Unity in the Community. They spent approximately four hours in the wreath making class creating holiday wreaths to give to Tulalip elders. “We are community members that have the ability to respond and so we want to do what we can. Utilizing resources that are already given seemed like the easiest place to start,” remarked Tulalip tribal member Bibianna Anchetta.

Offered to all those who participated in the wreath making festivity was a complimentary lunch comprised of traditional Tulalip cuisine. Inez Bill used her own elk meat to cook up an elk stew with nettles, Terri Bagley made a huge batch of fry bread, and Virginia Jones provided blackberry nettle lemonade and blackberry pudding. The blackberry used was the wild ground blackberry native to Tulalip. The stinging nettle used in both the stew and lemonade was harvested this past spring. “It’s a plant and fiber source that our people have used for a lot of different things. It has a lot of nutritional value and is one of the strongest fibers that anyone can use. It is nice to be able to offer our people some of these local, traditional foods when we come together,” Bill says of the stinging nettle and blackberry ingredients.

The holiday season is supposed to be about being around people you care about and showing them you care about them. For Inez Bill and the staff of the Hibulb’s Rediscovery Program, not only did they offer a wreath making class that allowed community members and guests to come together, but they showed their class attendees how much they care for them by preparing a traditional Tulalip lunch. It’s all part of adhering to traditional Tulalip values and traditions, Bill explains.

“Respect and caring. That’s what we try to share with our people when we work with them. A lot of people have forgotten those values. We are here to share that with our tribal membership. Something that was taught a long time ago by aunties and grandmothers and grandfathers we teach here, those teachings and values. Here we can keep that connection and share that connection to nature with our people. This is a living culture.”

by Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

Despite growing awareness, men usually take a back seat approach to maintaining their health. We will shy away from seeking advice, delaying possible treatment and/or waiting until symptoms become so bad we have no other option but to seek medical attention. To make matters worse, we refuse to participate in the simple and harmless pursuit of undergoing annual screenings.

Enter the Annual Men’s Health Fair held at the Tulalip Health Clinic on December 12. This year’s health fair provided us men the opportunity to become more aware of our own health. With various health screenings being offered for the low, low price of FREE we were able to get in the driver’s seat and take charge of our own health. Cholesterol screening, prostate screening, diabetes screening, and dental screening were among the options for men to participate in. Along with all the preventative health benefits of participating in these screenings, as if that was not reason enough, they gave out prizes and a complimentary lunch to every man who showed up.

At 16.1 percent, American Indians have the highest age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes among all U.S. racial and ethnic groups. Also, American Indians are 2.2 times more likelyto have diabetes compared with non-Hispanic whites (per Diabetes.org). Clearly we are at a greater risk when it comes to diabetes, making it all the more crucial to have glucose testing and diabetes screenings performed on an annual basis. For those men who attended the health fair, they were able to quickly have their glucose (blood sugar) tested with just a prick of the finger.

“The blood glucose test is a random check. Random is good, but doesn’t give you all the information which is why we do the A1C testing. It’s just nice to know if you are walking around with high blood sugar. This is a good way of saying ‘Hey, you need to go see your doctor.’ It’s not a definitive diagnosis,” said Nurse Anneliese Means of the blood sugar test.

Taking diabetes awareness one step further, an A1C test was available, by way of a blood draw that would also be used to test for high cholesterol.

“A1C is a diabetes screen. A1C is more of a long term indicator of glucose control as opposed to a regular blood glucose screening, which is here and now. A1C tells you what your blood glucose has been doing for the past 3 to 4 months,” states lab technician Brenda Norton.

How often should we have a diabetes screening performed? “Everyone should be checked once a year,” Norton said.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), heart disease is the first and stroke the sixth leading cause of death among American Indians. High blood pressure is a precursor to possible heart disease and stroke. High blood pressure is also very easily detected by having routine checks of your blood pressure taken periodically.

Nurse Tiffany Lee-Meditz states, “Measuring your blood pressure basically gives us a non-invasive look at your heart health. It can tell us if your heart is too large, if its beating too fast, if its pumping enough blood for the flow to get to all of your tissue and organs, and it can tell us if we need to look further. It can also tell us the health of your vasculature or your vessels, and if we need to look further into that.”

Along with the various health screenings being offered there were information booths available that ranged from alternative health care options in the local area, ways to have cleaner air in your home, and methods to change eating habits as to live a heathier life. There was a booth where we could have our grip tested, a method used for assessing joint and muscle fatigue. Another booth offered us the opportunity to have our BMI (body mass index) and body fat percentage measured. Wondering if you need to cut back on those weekend treats? Or if you need to start leading a more active lifestyle? Well if that BMI was too high and you didn’t like what your body fat percentage was, now you know the answer.

Face it, as we get older, we all need to become more aware of the inevitable health concerns that may one day affect us. The possibility of having to deal with high cholesterol, high blood pressure, diabetes, or the possibility of prostate cancer looms over us all. The only way to avoid such health concerns to heighten our awareness of these preventable conditions. Health educators empower us to be more proactive about our health by getting annual screenings, detecting issues early, as well as seeking medical treatment before a simple, treatable issue becomes life altering.

To all of the men who attended the Men’s Health Fair, Jennie Fryberg, front desk supervisor for the Tulalip Health clinic, issued the following statement, “Again thanks for all the men that came out today. Thanks for taking care of your health, and thanks for the staff that helped me today and made today a huge success for our men. Thanks again.”

Click the highlighted link below to download the December 24, 2014 Tulalip See-Yaht-Sub

Click here to download Dec 24 SYS

Lady Hawk #3 Myrna Redleaf

By Brandi N. Montreuil, Tulalip News

TULALIP – Fifteen-year-old Myrna Redleaf can easily be described as the most athletic player on the Lady Hawks team, evidenced by her strong baseline drives and her speed. Although a dual athlete playing both volleyball and basketball, winning isn’t what she is about. Sure she loves the glory that comes with winning, but she’s about being there for her team.

When asked why she chooses to play both sports she said, “I like both sports. I like to switch on and off.”

Redleaf has been playing basketball since 8th grade. Now in 10th grade at Heritage High School, she is in her second season as a Lady Hawk. In the 2013-2014 basketball season, Redleaf started as a point guard. That season her team would have an incredible record 22 wins and 4 losses, only meeting their toughest opponent during the trip-district championship games in the Neah Bay Red Devils. This year, Redleaf is one of few returning players and considered a veteran on the team.

Redleaf says she is still getting used to the switch of playing style between the two sports. “I get nervous when a lot of girls come at me. It is hard.” Unlike volleyball where physical contact isn’t part of the sport, basketball can have a lot of physical contact. When players make a drive down the court during an offensive play to go up to make a shot, a lot of contact can occur.

This season is off to a rough start as the Lady Hawks adjust to building the team camaraderie that it had last year. Many of the players on last season’s team graduated or switched schools. Redleaf explains the loss of key players, such as Katia Brown, Adiya Jones and Kalea Tyler, can be felt, but she is hopeful that this season will be great.

Despite feeling nervous to step in the spotlight and test her skills as a leader, Redleaf credits the mentoring style of coaching she receives with new Lady Hawks head coach, Cyrus “Bubba” Fryberg. “Last year there were a lot of good girls on the team so we didn’t go over as many drills as we are this year. I think more one-on-one is helping me.”

Dedicated and focused on and off the court, Redleaf, who’s favorite subject in school is math, says playing basketball has helped her focus and build confidence on the court as well as in school. “It helps me work as a team and communicate my thoughts.”

Her goal this season? Play hard and get a lot of shots in. As a scoring point guard, her main goal is to distribute the ball and get the players involved while also having to score, which means she has to have a good long shot, something she practices daily. “I practice a lot! I am still working on my long shots.” Her concerns are, “mainly shooting and handling the ball.” Despite playing one of the toughest games this season against Grace Academy, where the Lady Hawks were only able to score four points to Grace’s 49 and had over 20 turnovers, Redleaf is looking forward to meeting them on the court again.

“Grace was a tough game. There is a lot of stuff that we need to work on but other than that, we hustled pretty well during that game. I am looking forward to playing them again, or Highland Christian,” said Redleaf with her signature smile. “You just keep going. This is probably rock bottom and the only place we can go from here is up.”

Redleaf plans to attend college after high school to study business. She hopes to work in the human services field with the Tulalip Tribes.

Brandi N. Montreuil: 360-913-5402; bmontreuil@tulalipnews.com

By Brandi N. Montreuil, Tulalip News

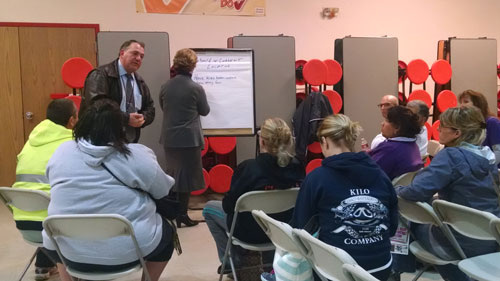

MARYSVILLE – “Our community has been shaken, shaken very hard by the events of October 24,” said new Recovery Directory Mary Schoenfeldt for the Marysville School District during a community meeting held on December 11, at Cedarcrest Middle School.

The meeting featured two topic agendas. For the first hour parents learned how to help their children process grief during the holidays. The remainder of the meeting focused on the future of the Marysville-Pilchuck High School cafeteria. Parents were able to voice their opinions during mini breakout sessions on what the school district should do to move forward.

The cafeteria was the location where 15-year-old Tulalip tribal member, Jaylen Fryberg, shot six students, killing five including himself. Since the October 24 incident the cafeteria has remained closed out of respect for students and the victims of the shooting. Now the school district is holding surveys asking the Marysville/Tulalip communities what they would like the future of the cafeteria to entail.

Before the breakout sessions, Schoenfeldt spoke to parents about depression and warning signs to look for in their children as the process of grief continues. “Your children will have a loss of concentration leading to short tempers or quick tempers. Watch for signs of grieving and depression in your children as suicide can become an issue.”

Schoenfeldt explained that students might have a hard time coping with the range of emotions that they are experiencing and may not know how to begin a conversation about how they are feeling. Many parents discussed the apprehension their children feel while at the school and trying to settle back into a routine. One mother expressed that her daughter texts frequently throughout the day as a way to cope and that she does not want to eat lunch at the school.

“Acknowledge that you are also having a hard time coping with your feelings. Acknowledging it with your child helps to make it a topic for discussion. Be available emotionally to your kids to listen to them,” said Schoenfeldt.

Following a brief Q&A with Schoenfeldt, parents were then invited to share their thoughts regarding the status of the cafeteria, which was built in 1970. The school district is seeking state funding to help rebuild the cafeteria.

Students temporarily are eating in the gym. “Right now we are just talking, where do we want the kids to eat? It can’t keep being at the gym forever,” said Dr. Becky Berg, Marysville School District Superintendent.

To decide if the cafeteria should be completely torn down or remodeled, the district had the community participate in a Thoughtexchange survey on the district’s website. “The intent is to get all our voice to the table and also include the students’ voices,” said Berg. The survey, which closed December 12, will be presented to the board.

“The intent of tonight, at this point, is to use these breakout sessions for those who haven’t been online yet and discuss possibilities that we haven’t considered,” said Berg.

Many participants expressed they would like to see the cafeteria radically changed in appearance so it would not be such a visible reminder of the October 24 event. Other suggestions included building in a new location, building in a contingency area or simply tearing it down.

The district is currently reviewing the surveys and waiting for funding approval. Berg remarked that while changes will take some time, it is being fast tracked for the students. “This will not be an overnight process. We are all first timers at this and hopefully last timers at this. Let’s keep talking and supporting each other.”

Brandi N. Montreuil: 360-913-5402; bmontreuil@tulalipnews.com