By Katie Campbell, OPB

MUKILTEO, Wash. — Near the ferry docks on Puget Sound, a group of scientists and volunteer divers shimmy into suits and double-check their air tanks.

They move with the urgency of a group on a mission. And they are. They’re trying to solve a marine mystery.

“We need to collect sick ones as well as individuals that appear healthy,” Ben Miner tells the divers as they head into the water.

Miner is a biology professor at Western Washington University. He studies how environmental changes affect marine life. He’s conducting experiments in hopes of figuring out how and why starfish — or sea stars, as scientists prefer to call the echinoderms — are wasting away by the tens of thousands up and down North America’s Pacific shores.

Watch the video report:

Scientists first started noticing sick and dying sea stars last summer at a place called Starfish Point on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. Then reports came from the Vancouver Aquarium in British Columbia, where diver biologists discovered sea stars in Vancouver Harbour and Howe Sound dying by the thousands.

It’s been coined “sea star wasting syndrome” because of how quickly the stars deteriorate. Reports have since surfaced from Alaska to as far south as San Diego, raising questions of whether this die-off is an indicator of a larger problem.

“It certainly suggests that those ecosystems are not healthy,” Miner said. “To have diseases that can affect that many species, that widespread is, I think is just scary.”

At first only a certain subtidal species, Pycnopodia helianthoides, also known as the sunflower star, seemed to be affected. Within a day or two of showing symptoms, the fat, multi-armed stars melted into piles of mush.

Then it hit another species, Pisaster ochraceus, or the common, intertidal ochre star. Then another. In all, about a dozen species of sea stars are dying along the West Coast. Sea star wasting has also been reported at sites off the coast of Rhode Island and North Carolina. But researchers say until they’ve identified the cause of the West Coast die-offs, they can’t confirm any connection between these outbreaks.

Scene From A Horror Film

Scuba diver Laura James was one of the first to notice and alert scientists when the morning sun star, Solaster dawsoni, and the striped sun star, Solaster stimpsoni, began washing up on the shores of Puget Sound near her home in West Seattle.

“I thought, ‘This is just getting a little too close for comfort, I need to go see what’s going on. And I need to document it,’” said James, an underwater videographer.

She decided to take her camera to a popular West Seattle dive spot, a place she knew to be a home to a rainbow of starfish. Underwater James discovered a scene from a horror film.

“There were just bodies everywhere,” James said. “There were just splats. It looked like somebody had taken a laser gun and just zapped them and they just vaporized.”

She returned the site weekly, tracking the body count. At first, young stars seemed to be hanging on, a sign of hope that the next generation might be spared, but then even the smallest succumbed.

James has been diving in Puget Sound for more than two decades and says she’s never seen anything like it.

“People always ask me, ‘Do you see any big difference between now and when you started?’” she said. “I’ve seen some subtle differences, but this is the change of my lifetime.”

Reports from recreational divers like James have made it possible for scientists to track the ebb and flow of the syndrome. That’s what led Miner and his dive team to Mukilteo — a place where sea stars showing initial symptoms could be gathered.

“It turns out that you just need a lot of people out looking to be able to detect the spread,” Miner said.

Miner’s team surfaced, laden with 20 giant orange sunflower stars. They gathered stars that appeared healthy and others that had lesions and weren’t acting normal -— unnaturally twisting their arms into knots.

Miner trucked the stars to an aquarium-filled lab and placed one sickly star in with one healthy looking star. He also set up tanks containing only healthy-looking stars for comparison.

Then he watched to see what would happen.

Within a few hours, the sick stars started ripping themselves apart. The arms crawled in opposite directions tearing away from the body. While starfish have the ability to lose their arms as a form of defense, these starfish were too sick to regenerate their arms. Their innards spilled out and they died within 24 hours.

As for the healthy looking stars, Miner said they didn’t show symptoms anymore rapidly by being in the same tank with sickly stars.

A few weeks later divers returned to Mukilteo to find that most of the sea stars there have died. Miner concluded that all of the stars his team had collected were likely already infected just experiencing varying stages of illness. His team has since continued other infectiousness experiments collecting stars from other areas of Puget Sound where the disease hadn’t yet surfaced.

One such place was San Juan Island, part of an archipelago in the marine waters of Washington and British Columbia.

An Opportunity For Science

“We’re holding steady here and we’re not sure why,” said Drew Harvell, a marine epidemiologist from Cornell University who has studied marine diseases for 20 years. She teaches an infectious marine disease course at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Labs on San Juan Island and was at the labs when the disease broke.

Harvell immediately recognized the die-offs as an important opportunity for science. Marine organisms are often plagued by disease outbreaks, she explained, but seldom are scientists able to identify the exact cause.

“We have a problem of surveillance for disease in the ocean because they’re out of sight and out of mind,” Harvell said.

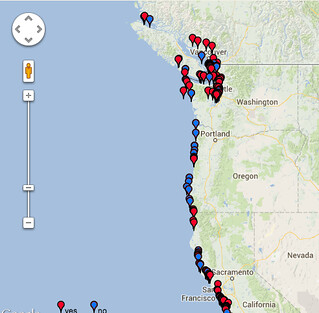

For the past few months, Harvell has been coordinating a network of scientists on both coasts who received rapid response funding from the National Science Foundation to investigate the die-offs. The team has established a website and map run by Pete Raimondi from the University of California Santa Cruz. It’s one of the fastest-ever mobilizations of research around a marine epidemic.

“This is an opportunity for understanding more about the transmission and rates of disease in the ocean, so it’s important that we gather the right kinds of data,” Harvell said.

In her lab, Harvell anesthetizes a healthy sea star before cutting off one of its arms and slipping it into a sterile bag. She’s sending samples to Cornell where her colleague Ian Hewson, a microbial biologist, will compare them with samples of sick sea stars from along the West Coast.

Using cutting-edge DNA sequencing and metagenomics, Hewson is analyzing the samples for viruses as well as bacteria and other protozoa in order to pinpoint the infectious agent among countless possibilities.

“It’s like the matrix,” Hewson said. “We have to be very careful that we’re not identifying something that’s associated with the disease but not the cause.”

Ruling Out Possible Culprits

In the search for what’s causing this sea star die-off, it’s important for scientists to rule things out. Some have suggested that these die-offs could be linked to low oxygen levels in the water and environmental toxins entering the water through local runoff. Yet this seems unlikely, they say, because these conditions would normally impact a wider array of animals, not just sea stars.

Others have pointed out that marine die-offs in the past have been linked to larger environmental factors like climate change and ocean acidification. Warming waters and changing pH levels can weaken the immune systems of marine organisms including sea stars, making them more susceptible to infection.

Some have asked whether radiation or tsunami debris associated with the Fukushima disaster could be behind this die-off. But scientists now see Fukushima as an unlikely culprit because the die-offs are patchy, popping up in certain places like Seattle and Santa Barbara and not in others, such as coastal Oregon, where wasting has only been reported at one location.

Others have wondered if a pathogen from the other side of the world may have hitched a ride in the ballast water of ocean-going ships. Scientists say this fits with the fact that many of the hot spots have appeared along major shipping routes. However, the starfish in quiet Monterey Bay, Calif. have been hit hard, whereas San Francisco’s starfish are holding strong.

But at this point, there’s no evidence to entirely confirm or entirely rule out these hypotheses.

A Sea Without Stars

Sea stars are voracious predators, like lions on the seafloor. They gobble up mussels, clams, sea cucumbers, crab and even other starfish. That’s why they’re called a keystone species, meaning they have a disproportionate impact on an ecosystem, shaping the biodiversity of the seascape.

“These are ecologically important species,” Harvell said. “To remove them changes the entire dynamics of the marine ecosystem. When you lose this many sea stars it will certainly change the seascape underneath our waters.”

Because the die-offs are patchy, scientists aren’t concerned that sea stars will be wiped out entirely. But there’s no end in sight and the disease continues to spread.

“We may still be at the very early stages of this. We don’t really know,” Harvell said. “But it’s as important as ever right now, that we’re monitoring to know where the disease hasn’t been yet and when it first hits.”

New experiments in Washington state started this week to test possible infectious agents. The network of scientists collaborating on this project hope to make an announcement in a few months.