Barrett Newkirk and Ian James

Originally posted by The Desert Sun | 10:40 p.m. PDT May 13, 2014

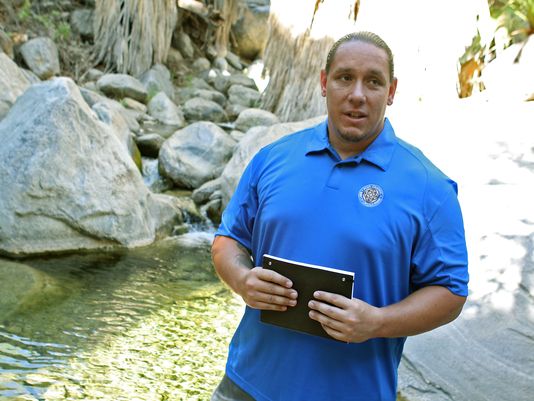

(Photo: Jay Calderon/The Desert Sun )

The U.S. Justice Department on Tuesday weighed in to support the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians in its lawsuit against two water districts, backing the tribe’s claims that the local agencies are infringing upon its rights by over-pumping groundwater from the Coachella Valley’s aquifer.

In the motion filed in U.S. District Court, attorneys for the Justice Department are seeking approval to join the lawsuit, saying the government has a significant interest in ensuring water rights for the tribe.

“Here, the United States shares the Tribe’s interest in protecting its water,” the motion states. “The United States recognizes that water is the ‘lifeblood’ of the Tribe’s desert homeland.”

In the motion, government lawyers said the U.S. government has an interest “in protecting the federal reserved rights to groundwater” associated with the tribe’s reservation. They said the tribe notified the federal government of the lawsuit and requested that it intervene.

In a separate complaint, the government’s attorneys asked that the court quantify the tribe’s right to groundwater “necessary to satisfy the purposes of the Reservation,” and noted that for decades, more water has been pumped from the Coachella Valley’s aquifer than has flowed back in — a condition known as “overdraft.” They said the water agencies’ use of groundwater “infringes upon the senior reserved rights of the Tribe.”

The federal government asked the court for an injunction to protect the tribe’s rights to groundwater and prevent the water districts from “injuring the Tribe … by overdrafting the groundwater.”

The tribe filed its lawsuit in May 2013 against the Desert Water Agency and the Coachella Valley Water District, the two largest water suppliers in the Coachella Valley.

“This action comes as no surprise to us as the federal government holds land in trust for the Tribe,” DWA Board President Craig Ewing said in an emailed statement. “DWA and CVWD, since their inception, have worked to ensure a safe, reliable drinking water supply for all of the residents of the Coachella Valley. We will continue to work to protect our customers as we have for decades.”

A spokeswoman for Coachella Valley Water District said the agency’s general manager and board members had not had time to review the motion and could not comment.

Robert Anderson, a professor at the University of Washington School of Law with experience in tribal water cases, called the government’s motion a significant development.

“It’s huge for tribal interests involved in the case that they’ve got the U.S. on their side now,” Anderson said.

The U.S. government will routinely get involved in lawsuits like this, Anderson said, but only when officials believe a tribe’s case has merit.

Anderson said he has no doubts the court will support the government’s request to intervene in the case. The added expertise and legal experience the federal government brings to the arguments could end up helping the tribe’s case, Anderson said.

In a statement, Jeff Grubbe, chairman of the Agua Caliente tribe, called the motion “a significant step in our fight to protect the future of Coachella Valley’s water supply.”

“For more than 20 years, the Tribe and the United States have raised concerns about the overdraft of the valley’s aquifer and degradation of the drinking water,” Grubbe said in the statement. “We are working to ensure the valley has a clean, abundant drinking water supply for generations. This move by the United States further proves the value and importance of our case against the water districts.”

A Desert Sun analysis of groundwater data determined that water levels in wells across the Coachella Valley declined by an average of 55 feet between 1970 and 2013. Those declines have been especially pronounced in the middle of the valley, with drops of more than 100 feet since the 1950s in some areas of Palm Desert and Rancho Mirage.

Water agency officials have said the tribe’s lawsuit seems to be an attempt to take away the public’s water rights, and have also suggested the tribe could be trying to make money off the water rights. The tribe has denied those accusations.

The Agua Caliente tribe has a reservation stretching across parts of Palm Springs, Cathedral City and Rancho Mirage, and owns two casinos and hotels. The tribe is preparing to develop a 577-acre piece of vacant land near its Agua Caliente Casino Resort Spa in Rancho Mirage into a 55-and-over residential community.

Leaders of the tribe have raised concerns about declining water levels in the aquifer and about worsening water quality due to inflows of imported water from the Colorado River with higher salinity levels. Water agency officials have stressed that the imported water is well within drinking water standards, and have said that treating the Colorado River water would lead to substantial rate increases for customers.

In February, lawyers for the water agencies and tribes appeared in federal court in Riverside, and District Judge Jesus Bernal set a timetable for pretrial procedures and motions, as well as a trial date of Feb. 3, 2015.

Attorneys for the Justice Department said in their motion that the government should be permitted to intervene in the case partly because “the United States asserts interests on behalf of all federally recognized tribes and all federal lands” relating to water.

A judge is scheduled to consider the government’s request at a hearing in Riverside on June 16.

Reach Barrett Newkirk at (760)778-4767, or by email at barrett.newkirk@desertsun.com