By PHUONG LE Associated Press

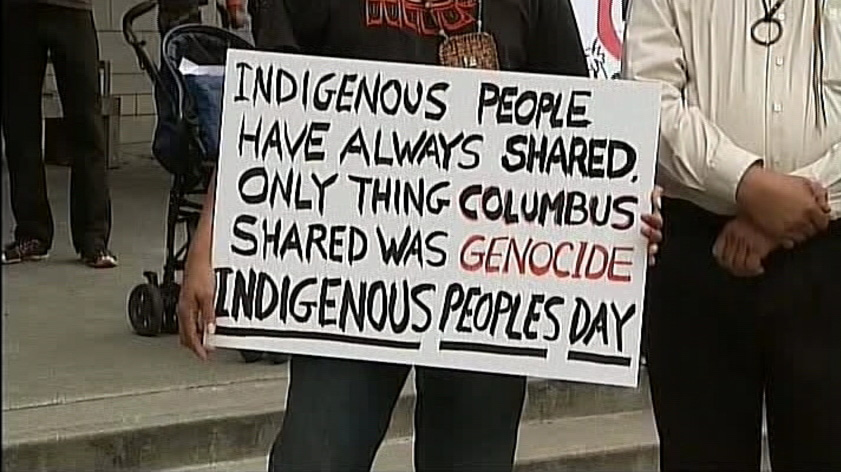

The Seattle City Council has voted to celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day on the same day as the federally recognized holiday, Columbus Day.

The resolution that passed unanimously Monday honors the contributions and culture of Native Americans and the indigenous community in Seattle. Indigenous Peoples’ Day will be celebrated on the second Monday in October.

Tribal members and other supporters say the move recognizes the rich history of people who have inhabited the area for centuries.

“This action will allow us to bring into current present day our valuable and rich history, and it’s there for future generations to learn,” said Fawn Sharp, president of the Quinault Indian Nation on the Olympic Peninsula. She is also president of the Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians.

“Nobody discovered Seattle, Washington,” she said to a round of applause.

Several Italian-Americans and others objected to the move, saying Indigenous Peoples’ Day honors one group while disregarding the Italian heritage of others.

Columbus Day is a federal holiday that commemorates the arrival of Christopher Columbus, who was Italian, in the Americas on Oct. 12, 1492. It’s not a legal state holiday in Washington.

“We don’t argue with the idea of Indigenous Peoples’ Day. We do have a big problem of it coming at the expense of what essentially is Italian Heritage Day,” said Ralph Fascitelli, an Italian-American who lives in Seattle, speaking outside the meeting.

“This is a big insult to those of us of Italian heritage. We feel disrespected,” Fascitelli said. He added, “America wouldn’t be America without Christopher Columbus.”

Seattle Mayor Ed Murray is expected to sign the resolution Oct. 13, his spokesman Jason Kelly said.

The Bellingham City Council also is concerned that Columbus Day offends some Native Americans. It will consider an ordinance Oct. 13 to recognize the second Monday in October as Coast Salish Day.

The Seattle School Board decided last week to have its schools observe Indigenous Peoples’ Day on the same day as Columbus Day. Earlier this year, Minneapolis also decided to designate that day as Indigenous Peoples’ Day. South Dakota, meanwhile, celebrates Native American Day.

Seattle councilmember Bruce Harrell said he understood the concerns from people in the Italian-American community, but he said, “I make no excuses for this legislation.” He said he co-sponsored the resolution because he believes the city won’t be successful in its social programs and outreach until “we fully recognize the evils of our past.”

Councilmember Nick Licata, who is Italian-American, said he didn’t see the legislation as taking something away, but rather allowing everyone to celebrate a new day where everyone’s strength is recognized.

David Bean, a member of the Puyallup Tribal Council, told councilmembers the resolution demonstrates that the city values tribal members’ history, culture, welfare and contributions to the community.