By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

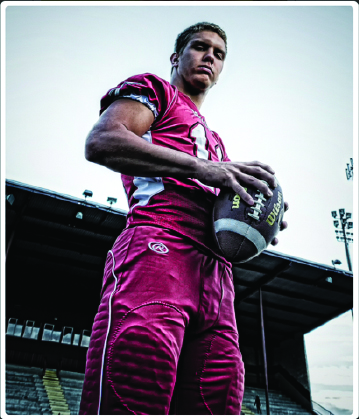

Many know Drew Hatch from his record-breaking athletic accomplishments on the football field and wrestling mat. For football, he was honored as the Everett Herald Defensive Player of the Year and earned 3A second-team honors on the 2014 Associated Press all-state football teams. For wrestling, he broke record after record on his way to becoming the most winning wrestler in Tomahawk history.

Yet, others know Drew from being a member of the Tulalip Canoe Family. He honors his Tulalip heritage by drumming and singing at community events. Many don’t know that Drew was one of five Marysville Pilchuck students honored with the Moyer Foundation’s annual Kids Helping Kids Award.

He has been an active member in his high school community, while remaining true to his roots as a Tulalip tribal member. Following his graduation from Marysville Pilchuck High School, the time has finally come for Drew to try his talents as both a student and an athlete at the next level, college. In order to do that he will be leaving the confines of the only home he has ever known. He is both prepared and excited to being his next journey.

When you look back at your high school years, what are some of your favorite memories?

“Most of them will definitely be sports related. Being able to play football and participate in wrestling with my friends and having fun being a part of that brotherhood. Both sports I enjoyed doing, they are what I’m most passionate about.”

You opted to attend Marysville Pilchuck High School (MP) instead of Heritage High School, were there any specific reasons as to why?

“My dad has been a wrestling coach at MP since I was in 5th grade. I practiced with their wresting team from 5th grade to 8th grade, so I had an established relationship with the wrestling coaches and football coaches long before I was high school age. One of my counselors at Totem Middle School was Brian McCutchen. He was also a football coach at MP and was one of my favorite people, so he also had a big influence on me to attend MP and be under his coaching.”

Following the MP shooting you really stepped up and took more of a leadership role at school, on your teams, and in the community. What made you step up like that?

“I saw how many people, friends, family and community members were down about everything. I knew that my whole football team had lost friends or relatives, I did too, but being a captain on the football team I’m responsible for holding that position. I wanted to be the person who had a hand out to help people in any way I could. Whether it was bringing someone to practice or just putting a smile on someone’s face, it’s all part of the healing process.”

What are your immediate plans following high school?

“I’ll be attending Oregon State University to play football and hope to receive a degree in Business Management.”

I’m sure you received a few different offers from colleges. Why did you choose Oregon State?

“I chose Oregon State because it felt the most like home. Corvallis is a small town where everyone knows each other but still offers everything that’s appealing about going to a university. It’s a good fit for me.”

Did you receive a football scholarship from Oregon State?

“I did not receive an official scholarship to play football, but I can earn one though. I’m on the football team as an outside linebacker and will be playing Pac-12 football, just not on a scholarship.”

Do you plan on wrestling at the collegiate level?

“I don’t plan on it. I might step in the room a little bit, but I won’t be committing to wrestling. Between the two sports, football is the one I’m more passionate about. Plus my focus is going to be split already between my studies and football.”

Being a student-athlete, you’ve been able to successfully carry that title. Most people know you from your success as an athlete, but you have remained dedicated to your studies as a student to the point you were recognized as the Male Student of the Year at the 2015 graduation banquet. How were you able to manage school with sports?

“It not easy that’s for sure. I struggled with my grades the first two years of high school. I was too focused on things away from school, like video games and hanging out with friends. As I matured, I realized I could still do those things but they’d have to come second to doing homework and studying. Once I realized that and made homework the priority and then did everything else after, things got easier. My study habits got better, which made taking tests and completing homework not as challenging.”

Are there any counselors or tribal liaisons who helped you stay the course, keep you motivated, or help you along the way?

“Matt Remle and Ricky B. played huge roles in me succeeding in and out of school. They were always checking on me and making sure I was keeping up my grades. They were always there to keep me in line and help me in any way they could, both academically and sports wise. They opened up doors that I didn’t even know were there, like with learning about tribal funding and tutors. They did a lot for me my entire high school career.”

Photo: Micheal Rios

You’ve recognized already that there will be huge differences from the high school level to the college level. What’s more important, playing college football or getting a degree?

“It’s been a lifelong goal of mine to play a college sport and I hope to accomplish that early on after my first OSU game. Being on that football field for the first time as an OSU Beaver will mean so much to me, but at the same time I know that sports aren’t the world. A degree is far more important because the likelihood of going pro in a sport is really low, but I know if I work hard and keep up my focus I can receive my Business degree and then use that accomplish more goals as an adult.”

Unfortunately, for many Tulalip tribal members their formal education stops at the high school level. You’ve chosen to take advantage of the Tribes ability to pay for your college education. What would be your message to those high school graduates of this year and in years to come in regards to taking full advantage of education after high school?

“I would say the Rez will always be here, your family will always be here. I’m not advocating going away forever, but go experience the world and achieve your goals as an independent adult. Then, when you have achieved your goals and experience life outside of Tulalip, you can come back with the knowledge and brain power to start your life back here. A high school diploma can only get you so far today. Getting an A.A. or B.A. will open so many more doors to you and give you options that wouldn’t otherwise be there.”