Category: Top Story

Federal appointment for Suquamish Tribe chairman

Suquamish Chairman Leonard Forsman … appointed by President Obama to the federal Advisory Council on Historic Preservation.

Source: North Kitsap Herald

SUQUAMISH — President Obama on Wednesday announced his intent to appoint Suquamish Tribe Chairman Leonard Forsman to the federal Advisory Council on Historic Preservation.

The announcement was made Wednesday by the White House Office of the Press Secretary. Forsman said the appointment will not affect his service as Suquamish chairman; the advisory council meets quarterly. It is not a paid position.

The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (www.achp.gov) is an independent federal agency that promotes “the preservation, enhancement, and productive use of our nation’s historic resources,” and advises the President and Congress on national historic preservation policy.

According to the agency’s website, “The goal of the National Historic Preservation Act, which established the ACHP in 1966, is to have federal agencies act as responsible stewards of our nation’s resources when their actions affect historic properties. The ACHP is the only entity with the legal responsibility to encourage federal agencies to factor historic preservation into federal project requirements.

“… the ACHP serves as the primary federal policy advisor to the President and Congress; recommends administrative and legislative improvements for protecting our nation’s heritage; advocates full consideration of historic values in federal decisionmaking; and reviews federal programs and policies to promote effectiveness, coordination, and consistency with national preservation policies.”

In a statement released by his press secretary, Obama said of Forsman and Margaret W. Burcham, who he intends to appoint to the Mississippi River Commission: “I am confident that these outstanding individuals will greatly serve the American people in their new roles and I look forward to working with them in the months and years to come.”

Forsman has been chairman of the Suquamish Tribe since 2005. He earned a bachelor of arts in anthropology from the University of Washington and a master of arts in historic preservation from Goucher College.

Forsman was director of the Suquamish Museum from 1984 to 1990, and has served on the museum Board of Directors since 2010. He was a research archaeologist for Larson Anthropological/Archaeological Services in Seattle from 1992 to 2003.

He has been a member of the Tribal Leaders Congress on Education since 2005, the Suquamish Tribal Cultural Cooperative Committee since 2006, the Washington State Historical Society board since 2007, and was vice president of the Washington Indian Gaming Association in 2010. He is also a member of the state Board on Geographic Names.

Forsman said, “I want to build on the advisory council’s efforts to recognize and protect those cultural resources that are important to Tribes — the cultural landscape and sacred places that have been neglected — and provide Tribes more resources to protect those places to the best of our ability.”

Hibulb Powwow honors Native American tradition

Source: The Herald

EVERETT — The 21st annual Hibulb Powwow is planned at Everett Community College on Saturday, featuring traditional American Indian dancing, drumming, singing and arts and crafts.

The theme for the event is “Keeping our Traditions Alive.” It is to be held at the college’s Fitness Center, 2206 Tower St. in Everett.

“The powwow honors cultural survival and the perseverance needed to celebrate and maintain Native identity into the 21st century,” according to a statement from Paula Three Stars, EvCC’s 1st Nations Club adviser.

The event is free. Everyone is invited.

This year’s head dancers are Reuben Twin, Jr., and EvCC student Christine Warner. The master of ceremonies will be Arnold Little Head. Tony Bluehorse will serve as the arena director. The host drums are Young Society and Eagle Warrior.

The Hibulb Powwow was founded in 1990 to honor American Indian ancestors who once lived near the mouth of the Snohomish River. Hibulb was the stronghold of the Snohomish peoples who thrived at the site just below Legion Park in Everett. Hibulb had an estimated population of 1,200 and was once the largest trading center in the Pacific Northwest.

Descendants of the people of Hibulb live today in the neighboring community of Tulalip, and on other nearby reservations representing many different tribal bands.

For more information, contact Three Stars at 425-388-9281 or Matt Remle at 360-657-0940.

Which Fish Get To Recolonize After Elwha’s Dams Are Gone?

May 9, 2013 | KUOW

CONTRIBUTED BY:Ashley Ahearn

This is the second in a two-part series..

From where Mike McHenry stands he can see several gray, torpedo-shaped bodies moving slowly through the brown water of this side channel of the Elwha River, not too far from the site of the largest dam removal project in U.S. history.

“You are looking at several wild winter steelhead. These are the native remnant stock of the Elwha River,” explains McHenry, the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe’s fisheries habitat biologist.

http://soundcloud.com/earthfix/hatchery-vs-wild-fish-in-elwha

These fish are some of the last wild steelhead in the Elwha – biologists estimate that there are between 200 and 300 left, and they’re here to spawn. But despite the fact that tearing down two dams has opened nearly 70 miles of pristine habitat on the upper Elwha River and its tributaries in the Olympic National Park, it’s made life rather difficult for fish in this river right now.

Millions of cubic yards of sediment and debris are flowing down from above the two dams, making this murky lower stretch of the river a bad place to spawn. But nevertheless, these few wild fish represent the prospect of a restored river, populated with thousands of salmon and steelhead – rivaling the numbers of fish that were here before the dams went in 100 years ago.

With that future in mind, McHenry and a team of field biologists and technicians are capturing, tagging and relocating these ready-to-spawn steelhead into a clear tributary of the Elwha, above the former site of the lower dam.

It’s a fascinating scene, filled with silvery flailing and splashing and men carrying fish from the pool up the hill to the waiting tanks to be anesthetized and tagged before the drive to the drop-off point upstream.

Then all that activity is brought to a halt by a slightly sleepy steelhead resting in a tank. It’s captured the attention of John McMillan, a contract biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“This is probably broodstock,” McMillan says.

Broodstock is another term for a fish that has spent time in a hatchery, even though its parents were wild.

This moment of discovery symbolizes a much larger debate playing out as different groups struggle over how best to rebuild the Elwha’s fish runs.

The Great Hatchery Debate

The 20th century wasn’t just an era of dam building in the Northwest. It’s also when hatcheries went up along the region’s rivers to supplement wild populations reduced by those dams, among other causes.

Some Native Americans support hatchery use as a way to restore fish runs that provided subsistence for earlier generations before the dams. But there are some who think hatcheries should not be used to speed up the return of wild, native fish.

It’s not just tribes that favor hatcheries on the Elwha as a way to provide a safe haven to keep native-origin steelhead alive in the tumultuous conditions that have accompanied dam removal.

“In this case what is very clear, crystal clear to us, is that the fish are in such bad shape and the conditions in the river are so unprecedented that any risk that the hatchery poses to these fish is more than outweighed by the benefits,” says Rob Jones, chief of production for inland fisheries with the National Marine Fisheries Service – one of the defendants in a lawsuit to stop the use of fish hatcheries on the Elwha.

Jones says wild steelhead numbers are dangerously low in the Elwha so the hatchery is necessary to steelhead survival. “The job is to help them hang on until these conditions improve enough and then, the strategy is, as we see that improvement that we start to phase out the hatchery.”

Jones says the hatcheries will be phased out when salmon and steelhead numbers increase, but the Elwha River Fish Restoration Plan does not give a set timeframe or hard date when the hatcheries will be removed.

Small-Brained Fish Or The JV Team?

Research has shown that when some types of salmon and steelhead are raised in hatcheries they can become domesticated. Other research suggests hatchery fish’s brains don’t grow as big and steelhead hatchery fish don’t produce as many offspring once they’re released. They’re also less likely to survive to adulthood than wild fish. But as the two hatcheries on the Elwha have demonstrated for years now, they’re a way to ensure that fish return to the river when conditions are hostile for wild, native fish.

The lawsuit over hatcheries in the Elwha recovery plan is a measure of how staunchly some groups oppose them.

“We believe that wild fish in the Elwha would recover better in the absence of hatchery influence,” says Jamie Glasgow, director of science and research for the Wild Fish Conservancy. “You cannot raise a fish in a hatchery without having a negative impact on it’s genetics and its behavior.”

The Wild Fish Conservancy is one of the non-profits that filed the lawsuit against the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, the National Marine Fisheries Service and several governmental agencies responsible for the Elwha restoration project.

The group says that hatcheries aren’t necessary for fish recovery in the Elwha, but if hatcheries are going to beallowed, it should only be for a limited time.

“From our perspective the plan lacks teeth,” says Glasgow. “It does not give us assurance and a real commitment to when hatchery production will be stopped.”

But keep in mind, the recovery process, underway on the Elwha right now, is unlike anything scientists have ever encountered. It is truly a grand experiment. No government or tribe has ever tried anything like this before – and no one knows exactly how it will play out.

Here’s the central question: with so few wild salmon and steelhead in the Elwha, should hatchery fish like be used as sort of junior varsity subs to boost the overall numbers of fish in this river as it recovers post-dam removal?

The science isn’t settled on how hatcheries impact wild fish, though there’s been a debate among fisheries managers on that for years.

Right now the Elwha is a difficult place to live if you’re a salmon or steelhead but it’s not impossible. Last year 500 wild Chinook made the journey above the lower dam to spawn on their own.

‘We Need To Make A Decision’

The debate over hatchery use in the Elwha recovery is playing out in real time as Mike McHenry stands over the tank and looks down at the fish with the nibbled dorsal fin that John McMillan has singled out as possibly coming from the nearby hatchery.

“Here’s where we need to make a decision,” he says, looking at McMillan.

Do the biologists bring these hatchery fish up into the pristine habitat above the dam? Or do they leave them here?

The team decides to bring two hatchery-raised fish upstream, along with six wild steelhead, to be released into the newly-available habitat above the former site of the lower dam.

McHenry leans down into the cold clear waters of this side creek and unzips a black bag. Two large steelhead slip slowly into the shadows along the bank nearby.

The biologists have DNA samples from all of the fish they’re releasing today – hatchery and wild. Mike McHenry and John McMillan say that will allow them to see who spawned with whom and which pairings led to more successful offspring.

“It’s a mixture, and that’s what we have,” McHenry says. McMillan nods his head in agreement.

“Yeah. It’s all we have to work with and you figure nature will sort it out ultimately. Nature sorts out who wins and who loses — and it will.”

For now anyway, nature is getting a little bit of help in the natural selection process.

Wednesday: Elwha River Recovery Proceeds Despite Sediment Setbacks.

New law targets how schools perform

By Jerry Cornfield, The Herald

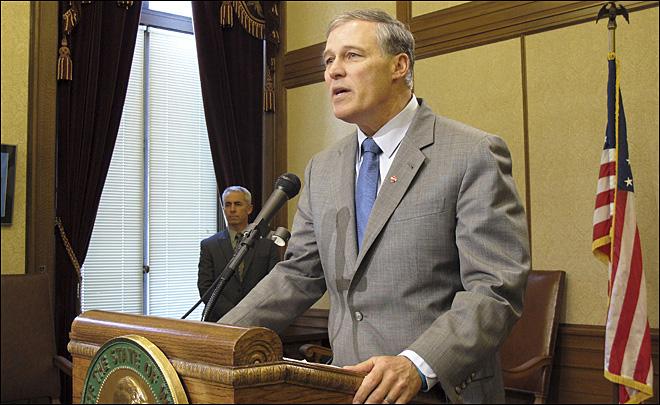

OLYMPIA — One of the first Republican-sponsored education reform bills became law Tuesday and will give the state more power to intercede in schools where student performance on basic skills tests is persistently poor.

Under the legislation signed by Gov. Jay Inslee, the superintendent of public instruction will provide technical assistance to schools where student scores on reading and math assessments are consistently poor for a period of years.

If the extra attention doesn’t improve student performance, the superintendent can impose a multi-year action plan on the school that prescribes such things as teaching methods and curriculum as well as how federal and state funds are spent on campus.

Superintendent of Public Instruction Randy Dorn said it is a “solid bill” which will enable the state to partner with targeted schools and shift to a leading role down the line if needed.

The prime sponsor of Senate Bill 5329 did not attend Tuesday’s signing but issued a statement calling it “a great step toward ensuring that all children are successful.”

“This was one of the important ways we can go about making sure our public-education system is serving all children and preparing them for the demands of an increasingly competitive job market and global economy,” said Sen. Steve Litzow, R-Mercer Island, who is chairman of the Senate Early Learning and K-12 Education Committee.

What Inslee signed is a far cry from the bill introduced by Litzow. That version required Dorn’s office to take over and manage poor performing schools starting in January 2014.

Pressure from House Democrats and the education establishment led to much revised language, which focuses on letting each school try to turn itself around before the state intervenes.

“We just don’t believe takeovers are a long-term solution to enacting real improvement in student achievement,” said Ben Rarick, executive director of the state Board of Education.

The final version sailed through the Senate on a 45-3 vote and passed the House on a comfortable 68-29 margin. The law takes effect in July.

In the House, opposition came from liberal Democrats, who thought it gave the state much power to intervene in local schools, and conservative Republicans who thought it did not go far enough.

Rep. John McCoy, D-Tulalip, voted to advance the bill out of the House Education Committee on which he serves then voted against it in the end.

He said it was being revised and improved from his perspective as it made its way through the House but did not reach the point where he could support it.

“We have overloaded schools with so many requirements, all in the name of accountability,” he said. “I am of the mindset that we need to give schools more leeway to get the job done. We have to give them the ability to teach.”

Meanwhile, Litzow and Senate Republicans are still pushing for action on a number of other education reform bills in special session.

One of those would evaluate the performance of every school using letter grades of A-F like on a report card. Student achievement is one of the measures that would be used in determining the grade.

Sen. Steve Hobbs, D-Lake Stevens, said the law signed Tuesday lays the foundation for such a system. “I think they complement one another,” he said. “In order to have a grading system that is meaningful you have to have clearly spelled out accountability standards.”

Inslee said the door is open for dialogue.

“I don’t think that this bill obviates the wisdom of continuing to look at some better ways to evaluate our schools,” he said. “I don’t think it’s the last of the discussion in that regard.”

North Dakota Visitor Center Honoring Sitting Bull Set to Open

Sitting Bull Visitor Center in North Dakota

Source: Indian Country Today Media Network

American Indian Alaska Native Tourism Association (AIANTA) Member Standing Rock Sioux Tribe will partner with Sitting Bull College for the ribbon cutting and open house of the highly anticipated Sitting Bull Visitor Center on May 15 from 11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m./MST at the Sitting Bull College Campus in Fort Yates, North Dakota.

Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairman Charles Murphy and Sitting Bull College President Dr. Laurel Vermillion will conduct the ribbon cutting ceremony at the Visitor Center’s Medicine Wheel Park, with a musical performance by flutist Kevin Locke, a National Endowment for the Arts Master Traditional Artist.

“This was a joint project of the Standing Rock Native American National Scenic Byway, Sitting Bull College and the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe,” said LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, AIANTA Board Member at Large and Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s Director of Tourism. “The new Sitting Bull Visitor Center and Medicine Wheel Park is a dream come true for us.”

The Sitting Bull Visitor Information Center, operated by Sitting Bull College, will offer travelers information regarding local and special events, places to visit, a gift shop that will sell a variety of authentic Native American arts and crafts, and more. The Visitor Center is also the new home to the Standing Rock Tribal Tourism Office operated by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. The Tourism Office provides Tatanka Okitika Historic Tours offering individualized tours on a first come first serve basis and reservations are recommended. Narrated tours are given along the Scenic Byway in both North Dakota and South Dakota. Stops include the Sitting Bull Burial Site, Standing Rock Monument, Standing Rock Tribal Administration Building, Sitting Bull Visitor Center and other points of interest.

Allard added, “We look to Native tourism to help our nation become sustainable for the future of our culture and people. We honor our great leader Sitting Bull with a center that will bring healing to our nation.”

“AIANTA is excited for our member the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and AIANTA Board Member LaDonna Brave Bull Allard,” said AIANTA Executive Director Camille Ferguson. “This is an example of how tribes are helping define, introduce, grow and sustain American Indian and Alaska Native Tourism.”

For more information about the Open House or to schedule a tour please contact LaDonna Brave Bull Allard at 701-854-3698 or lallard@standingrock.org.

AIANTA is a 501(c)(3) national nonprofit association of Native American tribes and tribal businesses that was incorporated in 2002 to advance Indian Country tourism. The association is made up of member tribes from six regions: Alaska, Eastern, Midwest, Pacific, Plains and the Southwest. AIANTA’s mission is to define, introduce, grow and sustain American Indian and Alaska Native tourism that honors and preserves tribal traditions and values.

The purpose of AIANTA is to provide our constituents with the voice and tools needed to advance tourism while helping tribes, tribal organizations and tribal members create infrastructure and capacity through technical assistance, training and educational resources. AIANTA serves as the liaison between Indian Country, governmental and private entities for the development, growth, and sustenance of Indian Country tourism. By developing and implementing programs and providing economic development opportunities, AIANTA helps tribes build for their future while sustaining and strengthening their cultural legacy.

Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe starts Washington Harbor restoration

Source: Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

The Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe is restoring salmon habitat in the 118-acre Washington Harbor by replacing a roadway and two culverts with a 600-foot-long bridge.

The 600-foot-long road and the two 6-foot-wide culverts restrict tidal flow to a 37-acre estuary within the harbor adjacent to Sequim Bay, blocking fish access and harming salmon habitat.

The Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe seined Washington Harbor to develop a baseline of fish populations in the harbor. The harbor’s roadway and two culverts will be replaced by a bridge later this summer. More photos can be found at NWIFC’s Flickr page by clicking on the photo.

The tribe seined the harbor in April to take stock of current fish populations before construction begins this summer. Chum and chinook and pink salmon, as well as coastal cutthroat, all use the estuary. Young salmon come from a number of streams, including nearby Jimmycomelately Creek at the head of Sequim Bay.

Historically, the area had quality tidal marsh and eelgrass habitat until the roadway and culverts were installed about 50 years ago, said Randy Johnson, Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe habitat program manager.

“The roadway and culverts appear to have severely degraded this habitat, with evidence showing that the estuary marsh has been deprived of sediment and is eroding,” he said. “The structures restrict access for fish and for high quality habitat to develop.”

Swinomish Tribe seeds beach for subsistence manila clam harvest

Source: Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

The Swinomish Tribe is developing a subsistence manila clam fishery on Lone Tree Point.

“We’re using habitat we already have to increase opportunities for our tribal members to gather shellfish,” said Lorraine Loomis, fisheries manager for the tribe. “Shellfish always have been part of our traditional diet and culture.”

In 2011, shellfish biologist Julie Barber seeded five test plots totaling 1,000 square feet with good survival results. Last summer, tribal members and staff seeded an entire acre of varied beach habitat north of the lone tree that gives the beach its name.

“This beach includes areas of desirable habitat such as sand and gravel, as well as areas of mud and fine silt, which is poor manila clam habitat,” said shellfish biologist Julie Barber. “Because the tribe will not be enhancing the poor substrate with gravel, as many commercial growers do, we avoided seeding these areas. Since the 2012 seeding, we have been monitoring survival and growth throughout the seeded area to determine how survival differs along the beach by location and elevation.”

Manila clams are a staple of many tribal shellfish programs because they survive at higher elevations in the intertidal zone than native littleneck clams, and are found in a shallower depth, so they are easier to dig. They reach a harvestable size two or three years after planting.

So far, survival seems to be better on the southern part of the beach, so the tribe plans to concentrate its efforts there. Some of the clams from the 2011 test plots could be harvested as soon as next summer.

Standing up for Religious Rights

Steve Robinson, Water4fish.org

AHOLAH, WA (4/30/13)– The government of the Quinault Indian Nation (QIN) is calling on the United Nations to undertake a special investigation into the treatment of American Indians in US prisons in connection with their right to exercise traditional religious practices.

In a letter sent recently to S. James Anaya, UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Geneva, Switzerland, Quinault President Fawn Sharp called for the United Nations representative to open immediate investigations with particular attention to prisons in the United States administered by the states of California, Texas, Montana, South Dakota and Washington.

The Quinault government joined the efforts of the Seattle-based non-governmental organization, Huy, pronounced “Hoyt” in the Coast Salish Indian Lushootseed language and meaning “See you again/we never say goodbye.”

In separate correspondence, Huy called for “an investigation into the pervasive pattern in the United States of increasing restrictions on the religious freedoms of indigenous persons who have been deprived of their liberty, particularly by American state corrections agencies and officers.”

“Indigenous peoples in the United States have the highest incarceration rate of any racial or ethnic group—38 percent higher than the national rate,” said Sharp, quoting a 1999 Bureau of Justice Statistics report. As of 2011, 29,700 indigenous persons were incarcerated in the United States—per capita the largest percentage of any ethnic group.

“But statistics aside, we cannot lose sight of the fact that these men and women are individual human beings and that, even as prisoners, there are certain rights they do retain, legally and morally. No government possesses the right to violate the laws of man or God in carrying out their punishment,” said Sharp.

The United States government is a party to international agreements that prohibit the violation of indigenous peoples’ religious rights. The Quinault government seeks to secure a United Nations sanctioned investigation to ensure that the United States will comply with human rights laws and agreements established over the last 60 years to fully protect American Indian, Alaskan Native and Hawaiian religious rights.

“Taking away the ability for these men and women to exercise their traditional spiritual practices is the same as saying rehabilitation is not important. It is a mindless, bullying tactic that contributes to recidivism,” she said.

“These actions go way beyond any reasonable level of punitive action and are more accurately described as anti-Indian activities,” said Sharp. “They constitute cruel and unusual punishment, and thus cross the line in terms of U.S. constitutional legality,” she said.

In 2010, the Washington Department of Corrections barred almost all American indigenous prisoners’ religious practices, banned tobacco, reclassified sacred medicines such as sage and sweet grass as non-religious, prohibited foods for traditional meals such as fry bread and buffalo, disallowed native children from attending summer prison powwows, and altered regulations so certain religious items could no longer be securely stored.

“Occasionally, the government-to-government relationship we have worked so hard to implement in Washington State does work,” said Sharp. “Ten tribes petitioned Governor Gregoire, and the Department of Corrections reversed course, consulting with tribal leaders about reforms and reaching an accommodation to restore American indigenous prisoners’ religious rights,” she said.

“But the fact that those bans could take place, even in this state—where we do have a working intergovernmental relationship—did illustrate both the larger pattern of rising restrictions on indigenous prisoners’ rights in this country as well as the importance of consultation with our tribal governments concerning administrative measures that affect our people. Another important thing this all points out is that, even in Washington, we have to remain ever-vigilant in the protection of all of our traditional values and rights. The state-tribal consultation and reform effort that resulted from this recent transgression by the state gave rise to Huy. We will support its efforts,” said Sharp.

“In the overall picture, we have to conclude that the United States is failing to fulfill its duty to protect the religious freedoms of American indigenous prisoners. There is a pervasive pattern of human rights abuses currently occurring in the United States in violation of both domestic and international law,” said Sharp. “We will oppose it.”

Legal Background

The U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples affirms that indigenous peoples have the right to “manifest, practice, develop and teach their spiritual and religious traditions, customs and ceremonies; the right to maintain, protect, and have access in privacy to their religious and cultural sites and the right to the use and control of their ceremonial objects. Other components of this same declaration further guarantee the protection of native tradition and cultural heritage, freedom from discrimination and provide that “States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative measures that may affect them.” The United States has signed on to this declaration.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights protects the right to freedom of religion, including the “freedom, either individually or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in worship, observance, practice and teaching.” That covenant further states that ethnic and religious minorities “shall not be denied the right, in community with other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, or to profess and practice their own religion.” It also provides that “freedom to manifest one’s religion or belief may be subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.” Human Rights Committee General Comment No. 22, para. 8 further clarifies that “persons already subject to certain legitimate constraints, such as prisoners, continue to enjoy their right to manifest their religion or belief to the fullest extent compatible with the specific nature of the restraint.”

Domestically, the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution enshrines the right to the free exercise of religion. The U.S. policy, as articulated in the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 is to “protect and preserve for American Indians their inherent right of freedom to believe, express, and exercise the traditional religions” of indigenous communities. With respect to prisoners, the federal Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act prohibits prison authorities from substantially burdening an inmate’s religious exercise unless in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest and accomplished by the least restrictive means. As the United States Supreme Court has recognized, prisoners “do not forfeit all constitutional protections by reason of their conviction and confinement in prison.” Bell v. Wolfish, 441 U.S. 520, 545 (1979).

Energy Department Announces $7 Million to Promote Clean Energy in Tribal Communities

Source: US Department of Energy

The Energy Department today announced up to $7 million to deploy clean energy projects in tribal communities, reducing reliance on fossil fuels and promoting economic development on tribal lands. The Energy Department’s Tribal Energy Program, in cooperation with the Office of Indian Energy, will help Native American communities, tribal energy resource development organizations, and tribal consortia to install community- or facility-scale clean energy projects.

Tribal lands comprise nearly 2% of U.S. land, but contain about 5% of the country’s renewable energy resources. With more than 9 million megawatts of potential installed renewable energy capacity on tribal lands, these communities are well positioned to capitalize on our domestic renewable energy resources—thereby enhancing U.S. energy security and protecting our air and water.

Through the “Community-Scale Clean Energy Projects in Indian Country” funding opportunity, the Energy Department will make up to $4.5 million available, subject to congressional appropriations, for projects installing clean energy systems that reduce fossil fuel use by at least 15% in either new or existing tribal buildings. Renewable energy systems for power generation only must be a minimum of 50 kilowatts and use commercial-warrantied equipment.

Through the “Tribal Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Deployment Assistance” funding opportunity, the Department will make up to $2.5 million available, subject to congressional appropriations, for projects installing renewable energy and energy efficiency that reduce fossil fuel use in existing tribal buildings by at least 30%. These projects must use commercial-warrantied equipment with renewable energy systems for power generation only of at least 10 kilowatts. Leveraging state or utility incentive programs is encouraged.

The full funding announcements are also available through the Department’s Tribal Energy Program website.

The Energy Department’s Office of Indian Energy and the Tribal Energy Program promote tribal energy sufficiency and foster economic development and employment on tribal lands through the development of renewable energy and energy efficiency technologies.

The Department has invested $41.8 million in 175 tribal clean energy projects over the years, and provides financial and technical assistance to tribes for the evaluation and development of their renewable energy resources, implementation of energy efficiency to reduce energy use, and education and training to help build the knowledge and skills essential for sustainable energy projects.