By Clayton Thomas-Muller, climate-connections.org

Years ago I was working for a well-known Indigenous environmental and economic justice organization known as the Indigenous Environmental Network (IEN). During my time with this organization I had the privilege of working with hundreds of Indigenous communities across the planet who had seen a sharp increase in the targeting of Native lands for mega-extractive and other toxic industries. The largest of these conflicts, of course, was the overrepresentation by big oil who work— often in cahoots with state, provincial First Nations, Tribal and federal governments both in the USA and Canada—to gain access to the valuable resources located in our territories. IEN hired me to work in a very abstract setting, under impossible conditions, with little or no resources to support Grassroots peoples fighting oil companies, who had become, in the era of free market economics, the most powerful and well-resourced entities of our time. My mission was to fight and protect the sacredness of Mother Earth from toxic contamination and corporate exploration, to support our Peoples to build sustainable local economies rooted in the sacred fire of our traditions.

My work took me to the Great Plains reservation, Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold to support a collective of mothers and grandmothers fighting a proposed oil refinery, which if built would process crude oil shipped in from a place called the tar sands in northern Canada. I spent time in Oklahoma working with Sac and Fox Tribal EPA under the tutelage of the late environmental justice warrior Jan Stevens, to learn about the legacy of 100 years of oil and gas on America’s Indian Country—Oklahoma being one of the end up points of the shameful indian relocation era. I joined grassroots on the Bay of Fundy, in an epic battle against the state of Maine and a liquidified natural gas (LNG) producer who wanted to build a massive LNG terminal on their community’s sacred site known as Split Rock. The plant, had it been built, would have provided natural gas to the City of New York for their power plants.

I worked extensively with youth on the Navajo reservation, in America’s Southwest, who were fighting the Peabody Coal mining company, to stop the mining of Black Mesa, a source of water and a known sacred site in the Navajo Nation. On the western side of the Navajo Nation, I worked to support Dine/Navajo that were fighting the lifting of the Navajo Nation ban on uranium mining, which would have seen the introduction of a dangerous form of uranium mining called in situ or “in place” extraction that would poison precious ground water resources in the desert region. Uranium had already left a devastating legacy on the Dine/Navajo from operations in the ’40s and ’50s. I worked in the Great Lakes region in the community of Walpole Island (Bkejwanong First Nation) to stop a oil company from drilling for oil in their fragile—a place where First Nations peoples harvest for wild rice, muskrat and fowl gains. It had also become a place of local economic importance as ecotourism from American duck hunters also providing income to the community. Walpole Island was already dealing with the impacts of 60 petrol-chemical facilities within 60 km of their nation. I worked to support groups in Montana’s Northern Cheyenne and Crow Indian reservations who were fighting massive expansion of Coal Bed Methane in their region. The encroachment was decimating local ground water resources. I worked in Alaska and was a co-founder of the powerful oil busting network known as Resisting Environmental Destruction on Indigenous Lands (REDOIL) which was created to take on the corrupt Alaska Native Corporations and big oil which had been running roughshod trying to start development in fragile places like the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). I worked with groups in British Colombia’s Northeast, where natural gas companies were ripping apart the landscape with massive gas developments in the region. I worked in dozens and dozens of other territories and places across the globe, many not mentioned in this story.

During my time as an IEN Indigenous oil campaigner for over five years (2001–2006) I observed that these fights were all life and death situations, not just for local communities, but for the bio-sphere; that organizing in Indian Country called for a very different strategic and tactical play than conventional campaigning; that our grassroots movement for energy and climate justice was being lead by our Native woman and, as such, our movement was just as much about fighting patriarchy and asserting as a core of our struggle the sacred feminine creative principal; and that a large part of the work of movement building was about defending the sacredness of our Mother Earth and helping our peoples decolonize our notions of government, land management, business and social relation by going thru a process of re-evaluating our connection to the sacred.

In the early years I often struggled with the arms of the non-profit industrial complex and its inner workings, which were heavily fortified with systems of power that reinforced racism, classism and gender discrimination at the highest levels of both non-profit organizations and foundations (funders). It was difficult to measure success of environmental and economic justice organizing using the western terms of quantitative versus qualitative analysis. Sure, our work had successfully kept many highly-polluting fossil fuel projects at bay, but the attempts to take our land by agents of the fossil fuel industry—with their lobbyist’s pushing legislation loop holes and repackaging strategies—continued to pressure our uninformed and/or economically desperate Tribal Governments to grant access to our lands.

The most high profile victory came during the twilight of the first Bush/Cheney administration when our network collaborated with beltway groups like the Natural Resources Defense Council and effectively killed a harmful US energy bill that contain provision in it that would kick open the back door to fossil fuel companies allowing access into our lands. The Indian Energy Title V campaign identified that if the energy bill passed, US tribes would be able to, under the guise of tribal sovereignty, administer their own environmental impact assessments and fast track development in their lands. Now this sounds like a good thing, right? Well, maybe for Tribal governments that had the legal and scientific capacity to do so, but for the hundreds of US Tribes without the resources, it set up a highly imbalanced playing field that would give the advantage to corporations to exploit economically disadvantaged nations to enter into the industrialization game.

Through a massive education campaign and highly-negotiated and coordinated collaborative effort of grassroot, beltway and international eNGOs—as well as multiple lobby visits to Washington DC lead by both elected and grassroots Tribal leaders—we gained the support of the National Congress of American Indians who agreed to write a letter opposing the energy bill to some of our champions in the US Senate most notably the late Daniel Akaka who was Hawaii’s first Native Senator. Under the guidance of America’s oldest Indian Advocacy group he would lead a vote to kill the energy bill in the Senate. This was my first view into the power of the Native rights-based strategic and tactical framework and how it could bring the most powerful government on Earth (and the big oil lobby) to their knees. Of course upon the reelection of the Bush/Cheney administration we lost the second reincarnations of the energy bill and the title V was passed.

What I learned in those battles was that because of the unique priority rights, the fiduciary obligation governments have to Native Americans—defined by the our sacred treaties and trust relationship and other unique legal instruments—we have an important tool as Native American and First Nations peoples. We are the keystones in a hemispheric social movement strategy that could end the era of big oil and eventually usher in another paradigm from this current destructive time of free market economics.

The challenge would be to get people with power, both real and falsely perceived, to understand this reality. It is a task not easily accomplished. For example with the passing of the US energy bill under the second US Bush/Cheney administration the US climate movement began to ramp up its attempts to have the administration pass a domestic climate bill. A massive investment by Washington DC focused on strategies developed by the foundations and individual donors, most of it was earmarked to policymakers instead of building an inclusive movement for climate justice that would take into account this environmental and economic justice frame in the struggle to force the US to lead the world in emissions reductions.

This movement saw the rise of mega-labour/eNGO coalitions like the Blue/Green Alliance, Apollo Alliance and mega-eNGO groups like 1sky and 350.org. Citizen groups like the US Public Interest Research Group (US PIRG) received millions of dollars to try and organize people to put pressure on President Bush and later President Obama to adopt some form of climate policy. However, the strategy screamed that age-old saying “what goes around comes around”…again. There would be no climate bill under Bush and, surprisingly to the people who voted for him, no climate bill under Obama (yet).

The groups that ended up receiving resources from a limited pot of climate funding did what they did best, which was to invest in top-heavy policy campaigns which did not focus on mobilizing the masses to get out in the streets; to target and stop local climate criminals and build up a bona fide social movement rooted in an anti-colonial, anti-racist, anti-oppressive foundation to combat the climate crisis. Instead it kept the discourse focussed on voluntary technological and market-based approaches to mitigating climate change, like carbon trading and carbon capture and storage. I would argue that this frame is what kept this issue from bringing millions of Americans into the streets to stop the greenhouse gangsters from wrecking Mother Earth. Groups like the Indigenous Environmental Network, Southwest Workers Union and others fought tooth-and-nail to try and carve out pieces of these resources to go towards what we saw as the real carbon killers, which were local campaigns being lead by Indigenous Nations and communities of colour to stop coal mining, coal fired power and big oil (including gas).

During the early hours of the Obama administration there was a massive effort to “green” the economic stimulus, this was a package of job creation funding that was to be doled out by the Obama administration to counter the Great recession, which had crippled the US economy. I had the opportunity to sit with some of the leaders of some of the biggest NGOs and foundations at a New York City roundtable, including members of the Obama White House team—high profile individuals like former Green Jobs Csar, Van Jones, and Energy Action/Mosaic Solar founder Billy Parish were also in attendance. At this table I told a story.

In the ’80s and ’90s America was in the grips of a recession, groups rose up from all sectors to create a strategy to combat the crisis. Alliances were formed between the trade unionists and the NGOs and social justice groups. When the negotiated target of funding was in sight and congress was about to write a check, groups became divided, and what was plentiful turned to scarcity and in the end AmeriCorp was born. Unions, NGOs and social justice groups, and more importantly, the unity they had created, was shattered. The political games and divisive tactics used by those in power who used race, class and gender politics to divided a movement. I said that we were in the exact same moment in time, that we were seeing big oil ram through an energy bill loaded with corporate welfare for the 1% during the collapse of Americas middle-class and the stalling of a US climate bill, would impact the most vulnerable to our rapidly destabilizing climate—poor communities of colour and Native American communities.

America’s wealth, and more directly, America’s energy infrastructure was built on our backs. Efforts should be made to invest locally first—from training green jobs workers locally to using local building materials to producing energy locally— which would close the financial loop will help revitalize Native America’s strangled economies, making them less vulnerable to volatile external costs while maximizing the positive impact of the new green revolution.

A green jobs economy and a new, forward-thinking energy and climate policy would transform tribal and other rural economies, and provide the basis for an economic recovery in the United States. In order to make this possible we had to encourage the Obama Administration to provide incentives and assistance to actualize renewable energy development by tribes and Native organizations and our allies.

I made the argument that we could use the attributes of a predatory economic paradigm, that had disproportionately targeted our communities, to flip the script on our enemies and that Native Americans, with our unique rights-based and trust relationship with the US government. It could be a strategic and tactical asset to a diverse social movement trying to lobby for an economic stimulus bill that would actually help empower the most vulnerable while not exacerbating an ecological crisis. For this to work we would have to make moral agreements and not, under any circumstances, be denied. On the table was $750 million earmarked for green jobs and the task at hand was to determine how to equitably share the pot. In the media, the numbers of jobs created versus the amount of workers unemployed went from one million to five million and then back to one million and again. Once we got to the point where congress was ready to write a check, we saw the downfall of mega groups like the Apollo Alliance and the absorption of the 1SKY by 350.org. Many groups who started off at the table fell, one by one, with the first being groups representing racialized constituencies. Meanwhile in Indian Country, tribes saw congressional allocations from this economic stimulus packaged in the billions (rightfully so) and kept on keeping on.

The point of the story was that if we could truly understand the aspects of our struggle that kept us united, and more importantly, understand what our unique contributions to a successful social movement paradigm, we could effectively expanded the pot from 750 million dollars to billions. By converging struggles in a solidarity framework rooted in anti-racism, anti-oppression and anti-colonialism and by creating economic and political initiatives uniting urban and rural centres, we could wield a power never seen by our oppressors and actually gain economic independence and community self-determination. We could develop economies that didn’t force people to have to choose between clean air, water and earth, or putting food on the table. I did not attend this meeting to ask for handouts, but rather as an ambassador of a strategic framework that I had come to know as the Native rights-based approach, which could be used to bring to an end what Native American activist, author and Vice Presidential candidate, Winona LaDuke described as “predator economics” and what activist and author, Naomi Klein rightfully describes as “shock doctrine” economics.

Little did I know that all of these experiences were preparing me for what would be one of the biggest battles of my life. During the IEN Protecting Mother Earth Summit in 2006 in Northern Minnesota, three woman from a small, mostly native, village called Fort Chipewyan, Alberta came to share their Dene peoples struggle—years later it would be known as the most destructive industrial project on the face of the earth, the tar sands mega-project. These three woman were related to each other and represented three generations of one prominent family in Fort Chip known as the Deranger clan. They listened to the dozens of stories told in the energy and climate group about the injustices happening because of oil companies and complicit governments across Turtle. They told us about a project so large, so devastating that you had to see it to believe it. They spoke of a wild west of sorts, one of the last bastions of Earth were big oil was ramping up, and they spoke of the deaths in their community from rare cancers, auto-immune diseases and boomtown economics that were plaguing their people who lived downstream from these tar sands. They said was that we needed to go up to Fort Chipewyan and help.

During this time I was taking time off from organizing and living in Ottawa with my wife and newly born son, Felix. My lifetime mentor and friend Tom Goldtooth, Executive director of the Indigenous Environmental Network took this invitation from the Deranger matriarch Rose Desjarlais very seriously. IEN immediately organized a fact-finding mission in the Athabasca region of the tar sands with our Native energy and climate director, Jihan Gearon, and Rainforest Action Network campaigner, Jocelyn Cheechoo, from the James Bay Cree in Northern Quebec. I was invited because of my experience in fighting big oil across Turtle Island.

When we flew into Fort McMurray, the boomtown in the heart of the tar sands, I was immediately struck by how much it reminded me of Anchorage, Alaska. That was the only other city I had ever been to that also reeked of oil money. The town had an infrastructure to support 35,000 people but was literally busting at the seams with a population of 75,000. Most were men between the ages of 18–60 and all working directly or indirectly for the tar sands sector. We took a tour of the infamous Hwy 63 loop to Fort McKay Cree Nation that carves thru man-made desert tailings ponds so big you could see them from outer space. We marvelled at the 24-hour life of the city and the incredible traffic jams at shift change. I think what struck me most was the level of homelessness in a town were there was six-figure salary for anyone who wanted it. To see the tar sands themselves was devastating, to fly over endless clear cuts, open-pit mines and smoke stacks surrounded by pristine Cree and Dene peoples homelands was gut wrenching. When we drove through and walked in the tar sands the smell of bitumen filled our noses and lent to the trauma that locals live with every day.

We got on a bush plane at the Fort McMurray airport and flew to Fort Chipewyan, we flew the route of the Athabasca River—a critical life path of the people of that land, a source of water, fish and transportation and a spiritual connection to a past. We were told of how the river had changed, become poisoned, was no longer safe and how every year the water levels became lower due to industry use. When we got to Fort Chip we were well taken care of, and we met many elders, the elected leadership and youth who all told the same stories of hardship, the untimely sickness and death, and the destruction of a subsistence way of life—all by the tar sands. We heard about the history of the peoples going out into the Athabasca Delta and on to Lake Athabasca for food and medicine and how that was becoming impossible due to the massive regional contamination by industry. Again we were told that we needed to help local grassroots people magnify this scandal to the world by amplifying their voices as the face of the issue.

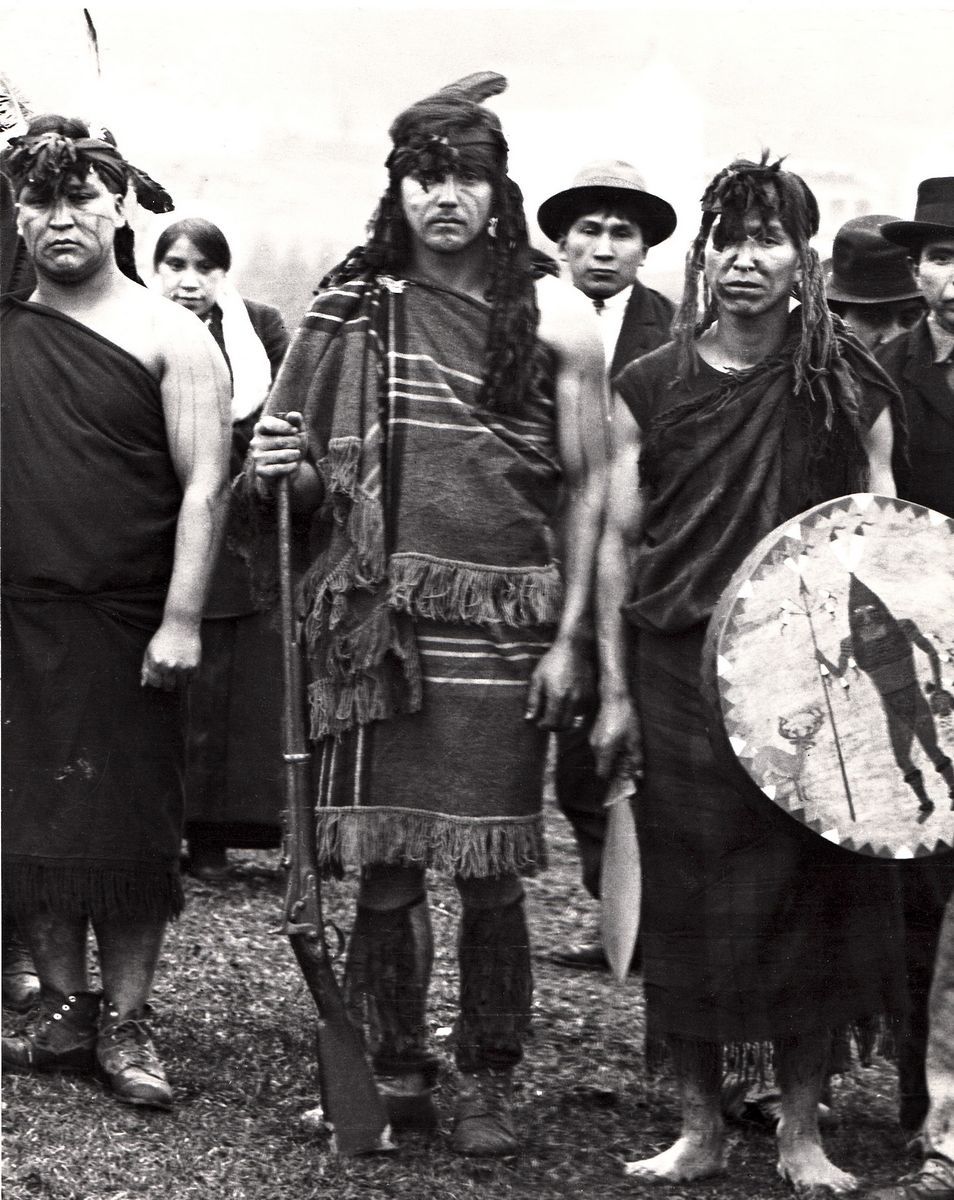

After we took in the horrifying science fiction of the tar sands—and more importantly the power, beauty and resiliency of the people of this land they call Athabasca—Tom Goldtooth asked me to build the Canadian Indigenous Tar Sands Campaign. The first thing we did was raise funds for an action camp in Fort Chip where we could do a proper power mapping and skill share with community members who were leading local campaigns and wanted to scale them up. Our first action camp had around 15 community members, including tar sands warriors and climate movement folk hero’s like former Mikisew Cree Nation Chief George Poitras, local Dene activists Mike Mercredi and Lionel Lepine, Melina Lubicon Massimo, a Lubicon Cree activist, and Eriel Deranger, a Dene woman also of Fort Chipewyan.

We brought in resource people from the NGO sector. With the direction of local Indigenous leaders we organized a series of workshops on Aboriginal Law, organizing, campaign planning, power mapping and the Native rights-based approach. The outcome of the camp formed directives to launch a Native-lead campaign to stop the expansion of the tar sands; to utilize a treaty and Aboriginal rights-based framework; to ensure that Indigenous peoples on the front line were the face of the campaign; to raise the human health impacts as a moral issue; to follow the money financing the tar sands and to target those controlling it. Also, we were to advocate in the non-profit industrial complex that a meaningful proportion of funding and resources earmarked for tar sands work go directly to First Nations.

What came next would consume most of my waking time on Mother Earth for the next seven years. When IEN launched our tar sands campaign we knew that this issue was about to become one of, if not the most, visible campaigns on the planet. The local grassroots peoples were engaging with the most ruthless, powerful, well-resourced and just plain old evil corporate entities on the face of the planet. We knew that these companies had bought every level of colonial government, and many were in bed with our own First Nations governments. But we knew that if executed properly we would see victory. This multi-pronged campaign would contain elements of legal intervention, base-building, policy intervention (at all levels of government, including the United Nations), narrative-based story-telling strategies in conventional and social media, civil disobedience and popular education and a whole lot of prayer and ceremony.

Again, I found my self at a table of funders and eNGO directors discussing a massive campaign that would impact every segment of our society including our bio-sphere. I found myself viewed by my peers as without power and that perhaps I was at the table for handouts rather then with something to offer. The same old tricks of top-heavy, policy-focussed pitches by the usual suspects happened again. And I found myself repeating the need to take the time to understand and work in solidarity with the Native rights-based strategic framework. I talked about how in the last 30 years of Canadian environmentalism there had not been a major environmental victory won without First Nations at the helm asserting their Aboriginal rights and title. This included many of the victories that those in the room counted in their own personal careers. I argued passionately that we should agree on the fact that we needed to dedicate meaningful resources this approach and the decision would mean the difference between a fight lasting years or decades. During that meeting the facilitator representing the collective of foundations and donors that had contributed to a pot of money to fund anti-tar sands work became noticeably frustrated with our platform and things escalated to a point were he was yelling and swearing that our IEN campaign was “in the way” of plausible strategies that were actually going to work. Once the chastising was over I proceeded to say “Well, now that I know were your coming from and you know where IEN is at, how much of this funding are we going to get?” We walked out of that meeting with 50 000 dollars seed money to start our campaign.

From that moment to now, our Indigenous heroes, or should I say “‘She’roes” have successfully built an international movement to stop the Canadian tar sands. Supported by thousands of Native and non-Native allies, the campaign is now active in the United States, Canada and Europe with hundreds of First Nations, unions, NGOs, private-sector companies, municipalities, foundations and individuals participating and elevating First Nations and our rights-based strategic approach as the keystone to the campaign. Part of this success was achieved through some seriously gutsy moves, one being a visit of high-profile Hollywood director, James Cameron, to tour the tar sands right when his blockbuster movie Avatar had become the highest grossing film in history.

Cameron’s tour was done at the time when IEN was pushing hard for our Keystone XL campaign to be funded. It was an uphill battle since everyone knew that pipeline fights historically have usually been defeats. We had done an analysis on the viability of victory in a Keystone XL campaign for the funders, this was due to the fact that we were one of the only groups that had taken on the Keystone number one pipeline. Our analysis told us a couple things; in the US, the Oglala aquifer would be the primary ecological card, as millions depended on this source of water and the pipeline was right through the heart of it. We knew that the dozen or so US Tribes could be educated to use the power of their unique rights-based approach to fight the pipeline. We also knew that no one in the USA, especially in the heartland of the Dakota states, Nebraska, Oklahoma and Texas knew what the tar sands were. We knew by bringing James Cameron to the tar sands, and by having him talk about the human rights scandal unfolding in First Nations communities, during a time whenAvatar was on every theatre screen on the planet would be huge boost to our cause.

Jim Cameron came, he saw, he met with the tar sands industry, the Alberta government and with First Nations. He made a lot of promises about direct support of the legal strategies of First Nations against the oil sector and the government of Canada. As an avid supporter of technological remedies, he did not condemn the tar sands, he spoke highly of nuclear energy as an alternative—as well as the emerging theoretical carbon capture and storage technologies. What he did do, was to say in front of the international press “I did not make Avatar until the technology was available for me to tell the story right, and the Canadian government should not develop the tar sands until they have the technology to not poison and kill First Nations people with cancers.”

Avatar part two and three are set to come out in 2015, I have a feeling that Cameron and his commitments to First Nations about directly funding the rights-based strategic framework are yet to be tested. The fall out from his visit was every newspaper, television, computer and smart phone in America was comparing the story of Avatar to the real-life situation unfolding between First Nations in the tar sands. The end result was the emergence of the Keystone XL campaign as the lightning rod of the US environmental movement, a fight that’s still raging today and it was done so thru the lens of human rights.

The tar sands campaign of IEN started at a time when direct community funding was in the tens of thousands but over time and through pressure it is now in the millions. We’re still dealing with a non-profit industrial complex that is its own worst enemy. But Harper’s corrupt, totalitarian federal government—with their extremism—is pushing a larger base of non-Native allies to our side of the equation.

With the current Harper government and the passing of recent omnibus legislation, Canada has seen 30 years of environmental, social and economic policy thrown out. In response, we seen the rise of Idle No More, a catchy social media and education campaign launched—again by First Nations woman—and the result was a quickening of Canadian reconciliation with its own violent history of colonization as well as the rapid politicization of tens of thousands of Indigenous peoples occurring not just in Canada, but in all occupied lands across Mother Earth. Left without a pot to piss in, the conventional non-profit Industrial complex and their supporters are trying to figure out their next steps in dethroning Harper, a daunting task after the unsuccessful bid to elect the New Democratic Party in British Colombia.

The one area the Harper government has not been able to stack the cards is the courts, and a Native rights-based tactical and strategic framework—supported by labour, NGOs, students and other social movements scaled up to the proportions of the 1960s US civil rights movement—is what’s going to not only dethrone Harper, but is the last best effort save our resources from Canada’s extractive industries sector and the banks that finance them. This rights-based approach has been tested time and time again, it is enshrined in section 35 of the Canadian constitution, it has been validated by more then 170 supreme court victories, it is validated by all of the Indian treaties, it’s validated by the United Nations declaration on Indigenous Peoples, it’s validated by the ILO convention 169 and many, many other legal instruments. The racism that Idle No More has met in the media reminiscent of a 1950 Mississippi era toward Native peoples and our winning rights-based strategy has driven even the most conservative of Canadians to our side and even toppled some of the biggest architects of the free market neoliberal agenda such as the infamous US-trained lawyer and mentor to Canadian Prime Minister Harper, Thomas Flanagan. We have come too far as Indigenous peoples to give up who we are, we have always been kind and again we will share the wealth and abundance of our homelands with our relatives from across the pond. Instead of lessons on how to survive the harsh winters of our lands, today we are offering lessons on how to be resilient and to overcome the oppression from the archaic oil sector and in our own government who have lost their minds with power.

We are faced with tremendous odds, the end of the era of cheap energy, the loss of ecosystems to sustain unfettered economic growth and, of course, the global climate crisis. We must understand that these are all symptoms of a much larger problem called capitalism. This economic system was born from notions of manifest destiny, the papal bull, the doctrines of discovery and built up with the free labour of slaves, on stolen Indian lands. We have much to do in America and Canada to bring our peoples into a meaningful process of reconciliation. I have learned that our movement is very much lead by woman, this is something I am very comfortable with given the fact that I am a Cree man and we are a matriarchal society. There is a powerful metaphor between the economic policies of this country Canada and the USA and their treatment of our Indigenous woman and girls. When you look at the extreme violence taking place againsts the sacredness of Mother Earth in the tar sands for example and the fact that this represents the greatest driver of both Canadian and US economies, then you look at the lack of action being taken on the thousands of First Nations woman and girls who have been murdered or just disappeared, it all begins to all make sense. Its also why our woman have been rising up and taking power back from the smothering forces of patriarchy dominating our economic, political and social and I would say spiritual institutions. When we turn things around as a peoples, it will be the woman who lead us, and it will be the creative feminine principal they carry that will give us the tools we need to build another world. Indigenous peoples have been keeping a tab on what has been stolen from our lands, which the creator put us on to protect, and there is a day coming soon were we will collect. Until then, we will keep our eyes on the prize, organize and live our lives in a good way and we welcome you to join us on this journey.

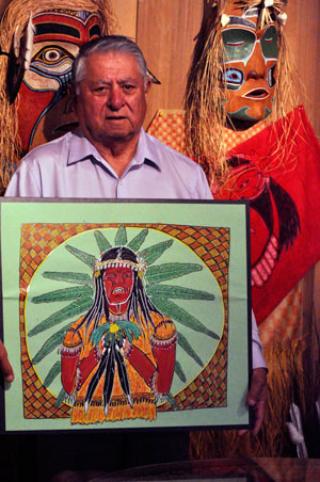

Clayton Thomas-Muller is a member of the Mathias Colomb Cree Nation also known as Pukatawagan in Northern Manitoba, Canada. Based out of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, Clayton is the co-director of the Indigenous Tar Sands (ITS) Campaign of the Polaris Institute as well as a volunteer organizer with the Defenders of the Land-Idle No More national campaign known as Sovereignty Summer.

Clayton is involved in many initiatives to support the building of an inclusive movement globally for energy and climate justice. He serves on the board of the Global Justice Ecology Project, Canadian based Raven Trust and Navajo Nation based, Black Mesa Water Coalition. Clayton has travelled extensively domestically and internationally leading Indigenous delegations to lobby United Nations bodies including the UN framework Convention on Climate Change, UN Earth Summit (Johannesburg, South Africa 2002 and Rio +20, Brazil 2012) and the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. Clayton has coordinated and lead delegations of First Nations, Native American and Alaska Native elected and grassroots leadership to lobby government in Washington DC, USA, Ottawa, Canada, and European Union (Strasbourg and Brussels).

He has been recognized by Utne Reader as one of the top 30 under 30 activists in the United States and as a “Climate Hero 2009” by Yes Magazine. For the last eleven years he has campaigned across Canada, Alaska and the lower 48 states organizing in hundreds of First Nations, Alaska Native and Native American communities in support of grassroots Indigenous Peoples to defend against the encroachment of the fossil fuel industry. This has included a special focus on the sprawling infrastructure of pipelines, refineries and extraction associated with the Canadian tar sands.

Clayton is an organizer, facilitator, public speaker and writer on environmental and economic justice. He has been published in multiple books, newspapers and magazines and appeared countless times on local, regional, national and international television and radio as an expert advocate on Indigenous rights, environmental and economic justice. He has been a guest lecturer at universities, conferences and seminars around the world. He is also a member of Canadian Dimension’s editorial collective.

Follow Clayton Thomas-Muller on Twitter: @creeclayton