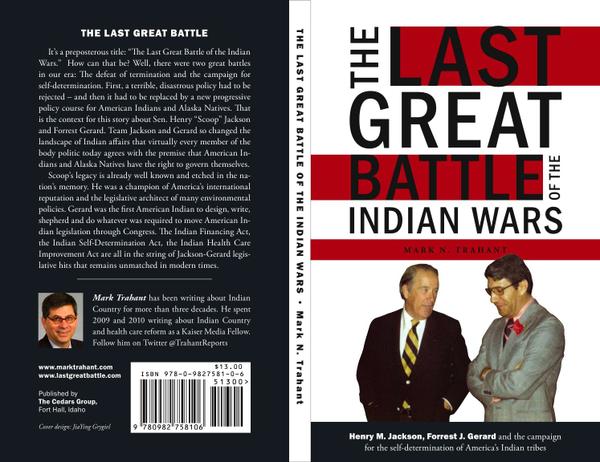

From left, Qualco Energy treasurer Dale Reiner president Daryl Williams and systems operator Andy Werkhoven discuss the company’s complex digester system that converts cow manure to electricity on Dec. 23. Qualco Energy recently signed a contract with the Snohomish County PUD.

By Bill Sheets, The Herald

MONROE — For the past five years, 300 homes outside Snohomish County have been powered by cow manure from farms near Monroe.

For the next five years, that power will stay in the county.

Qualco Energy, which runs a biogas plant south of Monroe, has been selling its power since 2009 to Puget Sound Energy.

Now, Qualco has signed a five-year contract with the Snohomish County Public Utility District, effective Wednesday.

The PUD provides electricity to Snohomish County and Camano Island. Puget Sound Energy, based in Bellevue, provides electricity to parts of eight counties in the region but not Snohomish.

The PUD “was able to offer a better rate than PSE did,” said Daryl Williams, environmental liaison for the Tulalip Tribes and a Qualco board member.

The PUD will pay Qualco $47.84 per megawatt hour in 2014, steadily rising to $67.60 in 2018, according to the utility. The price is based on a complex formula established by the PUD.

Qualco is a nonprofit formed by three groups: the energy division of the Tulalip Tribes; Northwest Chinook Recovery, a salmon advocacy group based in Anacortes; and the Sno/Sky Agricultural Alliance, a farmers’ group based in Monroe.

Qualco was created after cattle farmer Dale Reiner wanted to use a piece of property he’d purchased but was concerned about flooding and environmental effects on nearby streams.

He worked with Northwest Chinook Recovery on a fish habitat restoration project. Haskell Slough — a former main channel of the Skykomish River that had been diked off to create farmland — was restored into a salmon spawning stream. The project also has served to prevent flooding on Reiner’s property.

The unusual alliance of a farmer and environmentalists clicked, and the participants looked for another project. They brought in the Tulalip Tribes for added perspective on salmon habitat.

The group realized that making use of cow manure could help farmers and fish. Clearing farms of animal waste would reduce pollutants running into streams and cut costs for farmers in complying with environmental regulations. This, in turn, could allow them to add to their herds.

Biogas was the way, the group agreed.

Qualco was formed. The group obtained, through donation by the state, a former dairy farm in the Tualco Valley run by the Monroe Correctional Complex. The group also received a federal loan for renewable energy and a grant from the state Department of Agriculture. The equipment cost more than $3 million.

The group nets about $300,000 a year, Reiner said. The money goes to bond payments, environmental projects and upgrades to the system.

“None goes into our pockets, not a dime,” he said.

The work at the plant is done by dairy farmers on a volunteer basis.

The biogas plant uses the waste from about 1,200 cows. About 900 of them are located at Andy Werkhoven’s dairy farm about a mile and a half away. That waste is mixed with water and sent to the Qualco site via pipeline. The other 300 cattle are located on site next to the plant. Their only job is to eat and put out fuel for the generator.

Qualco also accepts unsold foods and beverages from stores, blood from meat processors and restaurant grease and uses it all in the mix. Qualco collects fees from companies to take the waste.

These materials are dumped into a concrete pit 15 feet deep and about 25 feet across, into which the liquid manure is piped.

An agitator with propeller blades churns the material into a swirling, roiling mix.

It’s then piped into a 1.4 million-gallon underground tank — 16 feet deep, 180 feet long and 74 feet wide — where it bubbles and gives off methane gas.

That gas is piped into a generator in a neighboring building, creating the power. The electricity is sent to the grid through three transformers mounted on a pole outside the building. The PUD is planning to replace those transformers with larger ones, Reiner said.

Previously, the energy went into the PUD’s system and the utility sent an equivalent amount to Puget Sound Energy. Now the power will stay home.

Effluent and solids from the process are applied to several farms as fertilizer.

Qualco’s original agreement with the state requires the fuel mix to be at least 50 percent cow manure and no more than 30 percent food-and-beverage waste. Qualco uses cow manure for the remaining 20 percent, creating a 70-30 ratio.

The sugars in the food waste, however, generate methane gas at a much higher rate than the cow waste, Qualco members said. As a result, the plant produces more gas than it can convert into electricity, and burns it off through an exhaust system.

While the generator creates enough power for about 300 homes, the plant produces enough gas for 800 homes, according to the Qualco website.

The plant would need another generator, or some type of expanded system, to take advantage of the remaining gas.

Qualco members plan to expand the plant, Reiner said. Options include steam power generation and compressing the fuel for use in cars.

“There are many directions we could go, and all of them are good,” he said.

Reiner believes the potential of biofuel is unlimited. Much more food waste and cow manure is available than is being used, he said.

Qualco could burn more food waste if it had the capacity and its agreement with state allowed it to do so, Reiner said.

He said any organic material that’s combustible could be turned into fuel.

“It’s just barely starting,” he said.