Contact Snohomish Health District to prevent rabies

syəcəb

By Tama Matsuoka Wong, Grist

Cross-posted from Food52

Foraged vegetables are always more fun to cook. So Food52’s resident forager, Tama Matsuoka Wong, is introducing us to the seasonal wild plants we should be looking for, and the recipes that will make our kitchens feel a little more wild.

If you’ve ever found a blueberry or a black raspberry on the side of a trail and popped it in your mouth, you’ve been foraging. Although it’s more convenient to “forage” farmers markets or grocery aisles for cultivated berries, I love the intense flavor of wild berries, as well as the fun of picking them in their natural habitat. Here is a rundown of some of the summer season’s most common wild berries:

Aggregate berries: Raspberries, blackberries, and wineberries

Aggregate berries are distinguished by their tightly packed clusters of fruits, known as carpels. The most common example is the raspberry, which is really a bunch of tiny red fruits clustered together. This sort of formation is a good thing, because each little fruit droplet on its own would hardly be enough for a mouthful!

These berries belong to the rose family, and grow on long arching “canes” that often form dense, brambly thickets. Much like roses, their bristles and thorns can make picking a somewhat prickly adventure — so be prepared!

“Crown” berries: Blueberries, huckleberries, and juneberries

Wild blueberries and huckleberries are in the Heath family, and grow as bushes or shrubs in soils with low acidity levels. While these are all bluish in color, the key identifier is that the edible blueberries all have a crown at one end.

It is important to note that there are several varieties of poisonous berries: Pokeweed, privet, honeysuckle vine berries, nightshade, and Japanese honeysuckle are all blue or purple in color; red-colored poisonous berries include bush honeysuckle and yew. Neither are aggregate fruits, nor do their berries have crowns. Always be sure to identify your plants, and do not just pop any old berry into your mouth as an experiment.

After a day spent foraging (and gobbling) berries in the woods, the last thing I want to do is spend a lot of time cooking, which is exactly why I tend to rely on store-bought pie crust for this incredibly simple pie. The pie is all berry, so their wild flavors shine through. It gets its zing from a bit of lemon and cassis, a trick I learned from my friend Betsy. It is also very flexible in terms of berry-to-berry ratios, so if I’ve eaten up most of the blueberries, I can just add more wineberries, and so on.

Mixed Wild Berry Pie with Cassis

See the full recipe (and save it and print it) here.

Makes one double-crust 9-inch pie

1 double pie crust (your favorite recipe, or store-bought)

5 cups mixed wild berries (I used 2 cups wineberries, 2 cups wild blueberries, and 1 cup mulberries)

1/2 cup sugar

1/4 cup cassis

Juice of half a lemon

Zest of 1 lemon

1/3 cup flour

Fruit jam (we used wineberry-blueberry jam from last year)

1 egg yolk (optional)

Raw sugar (optional)

By Andrew Gobin, Tulalip News

The Tulalip Karen I. Fryberg Health Clinic hosted their annual health fair July 28, with participants lining up at health screening stations, a fair first in 31 years,.

“I think this is the biggest health fair that we’ve ever had, there have been lines all day,” said Jennie Fryberg, front desk supervisor at the clinic. “More than 280 participants signed in, 200 of which were here before lunch.”

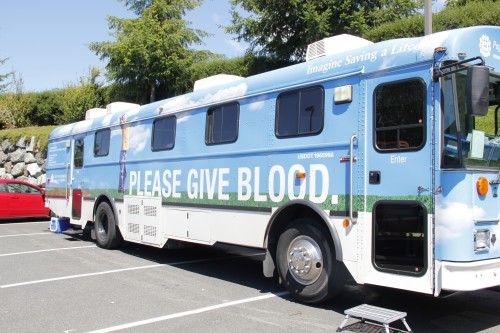

Every year, the clinic holds a blood drive simultaneously with the health fair. This year, more than 20 people had scheduled donor times with the Puget Sound Blood Center’s Blood Bus. Walk-ins are always welcomed at the Blood Bus, but there were so many walk-in donors this year, in addition to those with scheduled times, that for the first time at Tulalip, donors were being turned away due to lack of space. Of the 33 people who tried to give blood, 29 were able to.

With a record 35 booths, 8 screening stations, and a fun run, there seemed to be more interest in this year’s health fair than in previous years.

“People were here at 8:30 a.m. waiting for booths to open,” said Sonia Sohappy, a bowen therapist for the clinic’s complimentary medicine program.

The day started out busy, and really stayed comfortably crowded throughout the day. People stopped at screening stations, checking blood sugar, vision, blood pressure, tuberculosis, hepatitis, and more.

The annual health fair is one of many open house events at the Tulalip Karen I. Fryberg Clinic throughout the year. Watch for event announcements in the See-Yaht-Sub, on the Tulalip News Facebook page, or contact the clinic by phone at (360) 716-4511 for more information.

Andrew Gobin is a staff reporter with the Tulalip News See-Yaht-Sub, a publication of the Tulalip Tribes Communications Department.

Email: agobin@tulalipnews.com

Phone: (360) 716.4188

By Andrew Gobin, Tulalip News

You may have seen the blue and black Enagic water jugs people are packing around these days. You’ve probably heard about Kangen water, and if you yourself are not a Kangen user, you’ve probably wondered what exactly is so special about this water from all other filtered waters. The answer to which often leaves people with many more questions about how it all works, or why Kangen is a better choice. Here you will get an in-depth look at this latest health fad.

Many Kangen users tout this water as the new miracle in naturopathic health. Easily absorbed by the body, this water is supposed to keep you hydrated, in addition to being an antioxidant.

Tulalip tribal member Caleb Woods, a Kangen user, said, “I feel more energized, and toxins flush out of my body faster. I notice I sweat easier, and my acne has been clearing up.”

The effects Woods noted are typical of any well hydrated person, so what makes Kangen different? The answer is not so simple.

What is Kangen water exactly? In a nutshell, it is basic, or alkaline. The machine that filters and produces the water is actually a medical machine developed by a Japanese manufacturer 40 years ago. According to Kangen rep, Shawn Brown, water from the city tap or well goes into the machine, is filtered, and then restructured using electrolysis; a process of running an electric current through the water. Water molecules, which are naturally polarized, cluster in a naturally hexagonal structure, similar to a honeycomb. The restructuring of water arranges the molecules into micro clusters of five to seven molecules, instead of the typical 15. That process also ionizes the water, which makes it basic by creating a negative hydroxyl molecule (HO–) and a positive hydrogen ion (H+), or cation. Micro clusters of hydroxyl molecules are more easily absorbed in the body.

The separation of ions of Kangen water raises the pH, which is a measure of the power, or concentration, of hydrogen ions in any compound. The pH scale runs 1-14, 7 being neutral. As the concentration of hydrogen ions increases, the pH number decreases. Acids have low pH, and bases have high pH. Water typically measures at 7. According to the Snohomish County Health District, city water measures at 7.5 because of the lye added to the water to prevent rusting pipes, both hazardous to health in and of themselves. Kangen water is very basic when it’s ionized, measuring between 8.5 and 11, though agitating the water will return it to a neutral state. Also, if not consumed immediately, the natural interaction between the cations (H+) and hydroxyl (OH–) molecules will return the Kangen water to natural water (H2O).

What is the need for alkaline Kangen water?

Brown said, “Cities put a lot of chemicals in the water to kill bacteria, or to make the water healthy. Essentially, that is dead water. Kangen water is not only filtered, but it has free hydrogen ions, which is a natural antioxidant.”

The hydrogen cations are regulators that catalyze chemical reactions in the body’s systems, drawing out free oxygen molecules, or oxidants. In that way, the water is alive, interacting with the body as you drink it. The abundant of cations join with oxidants, neutralizing them. But Kangen water, as a basic solution, disrupts the body’s cells from doing this naturally by inhibiting the mitochondrial processes. The mitochondria of a cell, which govern metabolism in cells and in turn the body, require oxidants in order to metabolize proteins. Hydroxyl molecules join with free radicals making hyperperoxide in the body, allowing the free cations to seek out oxygen and oxidants to join with. That essentially leads to the depletion of oxygen creating a chemical imbalance in the body and a disruption of natural processes at a cellular level. This leads to premature cell death. The body works to regulate itself, and these processes occur naturally without Kangen water.

“The body is naturally alkaline, the blood is alkaline. If the body is acidic, you’re probably sick,” said Brown.

That is true, though not entirely accurate. The ideal pH of blood is between 7.3 and 7.4. So yes, it is alkaline, but only slightly. The body’s many systems help to regulate the pH of the body, each producing acids and bases, specific to each system. While the body is naturally alkaline by design, it is regulated through the secretion of acids produced in the body. Acids, like lactic and stomach acids, are designed to breakdown sugars and proteins, while bases, various hormones, are designed to specifically regulate systems in the body, many of which produce acids. Systems in the body use water to make hydroxyl and hydrogen cations for the purpose of metabolizing compounds and cleaning the body. It is a delicate balance that can have serious health implications when altered.

While it is a delicate balance, deviation of pH levels, even slightly, are signs of serious illness in the body. To do this intentionally has many health implications. For example, deviations in body chemistry of any degree affect metabolic systems drastically. A shock of pH imbalance due to raising the alkalinity of your body could lead to alkalosis. Mild alkalosis causes muscle spasms and cramps. Severe alkalosis can lead to tetanus or cardiac arrest. Acidosis, in contrast, causes mild nausea, vomiting, convulsions, and apnea.

Why does it matter, you may wonder? First of all, Kangen water will be available at all youth summer programs, and at the summer school. Parents should be aware that this is being served to your children. For people with strict dietary needs, there are serious health risks associated with altering body chemistry. That’s not saying Kangen is bad, or shouldn’t be used, but parents should be aware of what their children are exposed to. If people, including children, are on medications, they need to know how Kangen water affects them. The Kangen website and virtual demonstration specifically warn that users should not take medications with the alkaline Kangen water, and should refrain from drinking Kangen for an additional two hours afterward.

Second, there has been a large push that this is the answer to a healthier membership. There is a community Kangen machine available to the public for an hour, mornings and afternoons, at the Don Hatch Jr. Youth Center. Some members have machines in their homes. Kangen can only be acquired through the use of these machines, not sold in stores anywhere. These machines run between $2500 and $4000, and can be acquired through a regional Kangen representative. While the benefits of Kangen may outweigh the risks, the truth is, you don’t need Kangen water to be healthy. Similar results can be achieved through choosing organic foods and eliminating processed foods as much as possible, and expanding your diet to include foods that have specific benefits for healthy function of the body’s systems.

There is no magic cure all to ailments. While you can’t drink your way to health, it is beneficial to drink filtered water. To date, however, there is no documented medical suggestion that says basic water is healthier than natural water, in fact the opposite. Whatever water you choose to drink, the importance is to stay hydrated.

More info on Kangen water available online at www.kangenkarma.com. See the demonstration at www.kangendemo.com.

Andrew Gobin is a staff reporter with the Tulalip News See-Yaht-Sub, a publication of the Tulalip Tribes Communications Department.

Email: agobin@tulalipnews.com

Phone: (360) 716.4188

By Lynda V. Mapes, Seattle Times, July 21, 2014

Some tribal leaders and environmental groups say a water-pollution cleanup plan proposed by Gov. Jay Inslee this month is unacceptable because while it tightens the standards on some chemicals discharged to state waters, it keeps the status quo for others.

Inslee is drafting a two-part initiative to update state water-quality standards, to more accurately reflect how much fish people eat, and to propose legislation to attack water pollution at its source. The fish-consumption standards have the effect of setting levels for pollutants in water: The more fish people are assumed to eat, the lower the amount of pollution allowed.

Inslee decided that lowering some standards wouldn’t create a big-enough benefit to human health to justify the economic risk for businesses, said Kelly Susewind, water-quality program manager for the state Department of Ecology.

“The realistic gains on the ground didn’t warrant that concern and disincentive to invest in our state,” Susewind said.

That’s because the rules regulate state permits for dischargers, such as industrial manufacturers and wastewater-treatment plants — but that isn’t where most of the pollution is coming from.

Setting tougher standards for some pollutants would also result in levels too low to detect or manage with existing technology — but would create a regulatory expectation that could cloud future business investment, Susewind said.

“The concern is that we set in motion a chain of events where it is inevitable they can’t comply. If they are worried they will cease to invest in 30 years, they are not going to invest today; that is the long-term picture that caused the uncertainty.”

In the case of PCBs — polychlorinated biphenyls, industrial chemicals used as coolants, insulating materials, and lubricants in electric equipment — setting a limit below the existing limit of 170 parts per quadrillion wouldn’t improve people’s health, Susewind said. That’s because most PCBs are entering waterways from other sources, including runoff. “It is not the most effective place, to put the pinch on dischargers,” Susewind said.

The problem is that the Clean Water Act, under which the standards are issued, doesn’t reach beyond so-called point sources: pollution in water discharged from pipes by industries and others regulated by Ecology and the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

“A lot of our challenge is finding ourselves with only one tool,” said Carol Kraege, who leads toxics reduction at Ecology. “Getting toxics out of our water with just the Clean Water Act is not enough.”

To gain new tools to clean up state waters, Inslee has asked Ecology to put together legislation to expand its authority to ban certain chemicals, to keep them from getting in the water in the first place. The legislation, which is still being drafted, is intended to address so-called non-point sources of pollution.

The governor has said he won’t submit a final water-quality rule to the EPA for approval until after the legislature acts.

Christie True, director of King County Natural Resources and Parks, which runs the county’s wastewater-treatment plants, said she was encouraged by the governor’s approach. “We have to be focused on outcomes,” True said.

“The thing I was really happy about was he said we can’t just rely on regulating the same old sources if we want to improve water quality. I know it is going to be very challenging to take these issues to the Legislature, but that is where we need to head to have a better outcome.”

The debate now under way arose from the state’s need to update the water-quality standards that address health effects for humans from eating fish. The state’s rules today assume a level of consumption so low — 6.5 grams a day, really just a bite — that it is widely understood to be inadequately protective, especially for tribes and others who eat a lot of fish from local waters.

The standard also incorporates an incremental increase in cancer risk in that level of consumption.

Inslee has proposed greatly increasing the fish-consumption standard in the new rule, to 175 grams per day, a little less than a standard dinner serving. But he also upped the cancer risk, from 1 in 1 million under current law, to 1 in 100,000 in the new standard. That was to avoid imposing tighter standards for some pollutants.

That isn’t good enough for tribal leaders who say they want tougher protection now — for all pollutants, not just some. “Holding the line isn’t good enough,” said Dianne Barton, water-quality coordinator for the Columbia River Intertribal Fish Commission.

Counting on the Legislature to grant new authority to Ecology and money to back it up is also a shaky proposition, some said. “That is a big gamble,” said Chris Wilke, executive director of Puget Soundkeeper, a nonprofit environmental group that sued the EPA to force Washington to update its standards. Delay, meanwhile, “is more business as usual,” Wilke said.

Brian Cladoosby, chairman of the Association of Washington Tribes and the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, said tribes are going to take their case directly to the feds both at Region 10 EPA and in the EPA administrator’s office in Washington, D.C., and insist no change be made in the cancer risk.

“In our minds, the bar hasn’t moved that much,” Cladoosby said. “It took 100 years to screw up the Salish Sea; hopefully, it won’t take another 100 years to clean it up. But we have to start somewhere.”

Washington is slowly moving ahead with a long-delayed plan to update its water quality rules. Tuesday’s will be the first public meeting on Gov. Jay Inslee’s proposal to dramatically increase the fish consumption rate, which determines how clean discharged water must be. But some say the proposal doesn’t go far enough.

The governor’s plan would increase the fish consumption rate to about a meal a day, rather than a meal a month. It would increase the current rate of 6.5 grams per day to 127 grams per day. That’s the same rate recently adopted by Oregon, which has the strictest rate in the country.

“Well, yes, but it’s important to remember that that’s just one part of this equation,” said Chris Wilke with Puget Soundkeeper Alliance, one of four groups that sued the federal government last year to force it to make the state comply with the Clean Water Act.

Wilke says the plaintiffs are glad to see a more realistic fish consumption rate. But at the same time, he points out that Inslee’s proposal also lowers the bar on the allowable risk for cancer by a factor of 10, from one in a million to one in 100,000.

“It appears the state has kind of engineered the standards to come out where they want them to be or where might be acceptable to business interests,” Wilke said.

The state Department of Ecology says the Governor felt the compromise is necessary, because businesses have warned tightening the standard too much would prompt them to move jobs elsewhere.

And instead of just cleaning up the aftermath, Inslee is pushing for additional policies to discourage use of the chemicals in the first place, to “shift people away from using these kinds of things that are so problematic for the permit holders,” said Carol Kraege, who leads the state Department of Ecology’s toxics reduction efforts.

But the plaintiffs who brought suit for cleaner water say such policies might not make it through the Legislature. And they say a similar compromise was recently put forward in Idaho and rejected by the Environmental Protection Agency.

By NORA HERTEL Associated Press

PINE RIDGE, South Dakota — Denise Mesteth signed up for new health insurance through the federal Affordable Care Act, despite concerns that it may not be worth the money for her and other Native Americans who otherwise rely on free government coverage.

Mesteth, who has a heart murmur and requires medication and regular blood work, said she’s cautiously optimistic that the federal insurance will be superior to what she has now. Many other American Indians have been more reluctant to enroll, choosing instead to continue relying on the Indian Health Service for their coverage and taking advantage of a clause in the federal health reform law that allows them to be exempt from the insurance mandate if they meet certain requirements.

“If it’s better services, then I’m OK,” Masteth said of ACA. “But it better be better.”

Mesteth and other American Indians in South Dakota account for 2.5 percent of the people in the state who have signed up for insurance under the federal health care law, according to the latest signup numbers. The state, with nearly 9 percent of its overall population Native American, ranks third for the percentage of enrollees who are American Indian among U.S. states using the federal marketplace.

The Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Health Board, which provides support and health care advocacy to tribes, received $264,000 to help Native Americans in South Dakota navigate the new insurance marketplace.

Tinka Duran, program coordinator for the board, said people are primarily concerned about the costs of enrolling. Insurance is a new concept to most because health care has always been free, she said.

“There’s a learning curve for figuring out co-pays and deductibles,” she said.

During a U.S. Senate Indian Affairs Committee hearing in May, tribal leaders chastised IHS as a bloated bureaucracy unable to fulfill its core duty of providing health care for more than 2 million Native Americans and Alaska Natives. IHS acting director Yvette Roubideaux said changes were underway but that more money will be needed than the $4.4 billion the agency receives each year.

She noted that federal health care spending on Native Americans lags far behind spending on other groups such as federal employees, who receive almost twice as much on a per-capita basis. Meanwhile, American Indians suffer from higher rates of substance abuse, assault, diabetes and a slew of other ailments compared to most of the population.

Native Americans and Alaska Natives are exempt from the health insurance mandate if they meet certain requirements. ACA also permanently reauthorized the Indian Health Care Improvement Act and authorized new programs for IHS, which also is starting to get funds from the Veterans Affairs Department to help native veterans.

When American Indians do obtain insurance, it means fewer people are tapping the IHS budget, said Raho Ortiz, director of the IHS Division of Business Office Enhancement.

“If more of our patients have health insurance or are enrolled in Medicaid, this means that more resources are available locally for all of our patients,” Ortiz said in an emailed statement. “This, in turn, allows scarce resources to be stretched further.”

Those who sign up for federal health care can still use IHS facilities but have the option of seeking health care elsewhere, Ortiz said.

State Democratic Sen. Jim Bradford is among the skeptics. The Oglala Sioux member lives on the Pine Ridge reservation, home to two of the poorest counties in the nation.

The U.S. government provides health care to Native Americans as part of its trust responsibility to tribes that gave up their land when the country was being formed. Bradford and others object to the shift in health care providers on the principle that IHS is obligated by treaty to supply that care.

Harriett Jennesse, a member of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe who lives in Rapid City, said she already has seen the benefits of the new health insurance and doesn’t mind paying a little out of pocket.

Jennesse said she put off treatment for a painful bone chip in her elbow after IHS denied a doctor’s referral to a specialist on grounds that it wasn’t an urgent enough need. She’s now seeing a specialist for dislocation in her other elbow and will also try to get the bone chip fixed when the other arm heals.