Category: Environment

Earth Day Beach Clean-up at Mission Beach, April 23

Being Frank: Poor coho returns demands caution

By LORRAINE LOOMIS, Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

There likely will be no coho fisheries in western Washington this year as returns are expected to plummet even further than last year because of poor ocean survival.

Coho returns in 2015 were as much as 80 percent below pre-season forecasts. The Nisqually Tribe canceled its coho fishery when fewer than 4,000 of the 23,000 fish expected actually returned. The same story was repeated in many Tribal fishing areas.

That’s why western Washington treaty Tribes are calling for greater caution in fisheries management planning this year and more equitable sharing with the state of the responsibility for conservation. It is important that we have agreement on in-season management methods and actions before the season starts.

Unlike sport fishermen who can go where fishing is best, Tribal fishermen are bound by treaty to traditional fishing places located mostly in terminal areas — such as rivers and bays — that are the end of the line for returning salmon.

Every year, we must wait and hope that enough fish return to feed our families and culture. Faced with low catch rates last year, however, most Tribal coho fisheries were sharply reduced or closed early to protect the resource. The state, however, expanded sport harvest in mixed stock areas last year to attempt to catch fish that weren’t there.

That’s not right. The last fisheries in line should not be forced to shoulder most of the responsibility for conserving the resource.

Making matters worse, lack of monitoring by federal fisheries managers last year allowed Southeast Alaska commercial fishermen to exceed their harvest quota by more than 100,000 chinook. Most of those fish were bound for Washington waters.

Coho salmon that managed to make it back last year showed frightening effects of poor ocean conditions. Most were 20 to 30 percent smaller than normal. Females returned with about 40 percent fewer eggs. That will likely result in lower natural and hatchery production and fewer fish in the future.

Right now, what salmon need is plenty of good habitat to increase stock abundance and build resiliency to survive the impacts of climate change and poor ocean conditions. Sadly, salmon habitat continues to be lost and damaged faster than it can be restored, threatening the future of the salmon and tribal treaty-reserved harvest rights.

Fisheries management is about the future, and the future doesn’t look good for salmon if we don’t reverse the trend of habitat loss and damage. Perhaps most of all we need a commitment from state and federal fisheries managers that the same high conservation standard that Tribal fisheries are held to will be applied to all other fisheries. That includes making the tough decision to close some fisheries to protect returning salmon for everyone.

— Lorraine Loomis is chairwoman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission. Commission members include the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe and the Suquamish Tribe.

Cities, counties and tribes seek limits on oil and coal shipping

By Chris Winters, The Herald

EVERETT — Oil train explosions might grab headlines, but there are a number of other issues surrounding the shipment of fossil fuels that are bringing a diverse group of local leaders together.

SELA, the Safe Energy Leadership Alliance, is providing a forum for local leaders to work together to protect their communities from the negative effects of rising shipments of oil and coal.

More than 150 public officials are listed as members, including mayors and city council members from many Pacific Northwest cities that lie on major rail lines, such as Edmonds, Mukilteo, Everett and Marysville.

SELA’s latest meeting, the sixth since the group was established, included several tribal leaders, uniting native and non-native leaders around a common interest.

“I think this is one of the first initiatives that brings us all together,” said Tulalip Tribes Chairman Mel Sheldon Jr., who attended the Feb. 4 meeting at Everett Community College.

King County Executive Dow Constantine organized SELA a year and a half ago, and the group’s influence now extends into Oregon, Idaho, Montana and British Columbia.

A regional organization is needed to counter the power that international oil, coal and railroad companies have, he said.

“Local elected officials acting individually won’t be able to have an impact on the global or national issues,” Constantine said.

And yet, local communities bear the effects of those same industries, whether it’s the risk of oil spills or fires, coal dust blowing out of passing hoppers, or even traffic jams in cities such a Marysville with a high number of at-grade crossings.

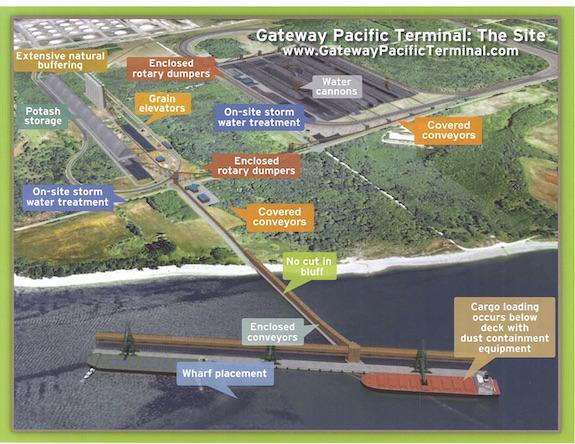

For Tim Ballew, chairman of the Lummi Nation, the issue hit home when SSA Marine applied to build the new Gateway Pacific coal terminal at Cherry Point, close to the Lummi Reservation.

The Lummi were joined by several other tribes, including Tulalip and the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, in opposing the project.

Ballew told the SELA attendees that effects of increased shipping on native fishing grounds as well as the development of the terminal in an area of spiritual and archaeological significance present a challenge to the tribe’s treaty rights.

“At the heart of the issue, with all of these negative impacts that will come to our community and compromise the integrity of the place we live in, the benefits won’t really go to the people,” Ballew said.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is expected to issue a ruling soon on the project’s permit.

Keeping the focus on a single issue has allowed SELA to transcend partisan boundaries, too, Constantine said.

Tribes seek to protect their treaty rights, cities fear derailments and traffic blockages, and rural communities find that fossil fuels are taking up more rail capacity and squeezing out agricultural products.

One 2012 study by the Western Organization of Resource Councils predicted that rail traffic of wheat, corn and soybeans will have to compete with coal and oil for space on trains, resulting in longer delays in getting to market. There were 38.3 million tons of agricultural products shipped to Asia through Pacific Northwest terminals in 2010.

“Farming and ranching and orchards are tough enough businesses without piling on the added burden of getting goods to market,” Constantine said.

David Browneagle, vice chairman of the Spokane Tribe of Indians, pointed out that pollution ultimately doesn’t discriminate who it affects.

“Coal dust will go into all our lungs together,” Browneagle said. “It’s not going to come off the train and say ‘Hmm, that’s an Indian, so I’ll go in him.’ ”

He added his great-great grandfather tried and failed to prevent the railroads from arriving in Indian Country, but that it’s a good thing that this group was doing something now to push back.

Megan Smith, director of Climate and Energy Initiatives in Constantine’s office, has been tracking progress and the public comment windows of new terminal projects in the northwest, as well as coordinating those comments from a large number of local officials.

So far, SELA members have sponsored successful legislation in Olympia, in the form of tougher safety regulations on oil trains, as well as in Oregon, which has enacted a similar law, Smith said.

The work won’t stop at Cherry Point or with a few state laws. Another proposal, the Tesoro Savage oil terminal in Vancouver, Washington, will enter the environmental review stage possibly by the end of the year, said Beth Doglio, the campaign director of the environmental nonprofit Climate Solutions.

Tesoro Savage could become the largest terminal on the West Coast, Doglio said. The oil and coal boom is fueling interest in other projects all over the country.

“We are definitely a movement together that has been very strong, very clear in the message that this is not what we want in the state of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and North Dakota,” Doglio said.

Tulalip Chairman Sheldon said SELA is helping different groups learn to work together and trust each other. That may lead to identifying other common interests.

“When you get leaders coming together with good issues, issues that bond us together, that to me really is the formula for success,” he said.

State still obstinate on tribal rights; fix culverts to save salmon, now

The money, time and effort spent denying tribes their rights could be far better spent on salmon recovery.

THE state of Washington should end its long, failed history of denying tribal, treaty-reserved fishing rights and halt its appeal of a federal court ruling requiring repair of hundreds of salmon-blocking culverts under state roads.

Instead, the state should embrace the court’s ruling, roll up its sleeves and work with tribes to end the spiral to extinction in which the salmon and all of us are trapped.

The money, time and effort spent denying tribes their rights could be far better spent on salmon recovery. More salmon would mean more fishing, more jobs and healthier economies for everyone.

The appeal stems from Judge Ricardo Martinez’s 2013 ruling that failed state culverts violate tribal treaty rights because they reduce the number of salmon available for tribal harvest. Martinez gave the state 15 years to reopen 90 percent of the habitat blocked by its culverts in Western Washington. More than 800 state culverts thwart salmon access to more than 1,000 miles of good habitat and harm salmon at every stage of their life cycle. The state has been fixing them so slowly it would need more than 100 years to finish the job.

The U.S. government filed this case in 2001 on behalf of the tribes. It is a sub-proceeding of the U.S. v. Washington litigation that led to the landmark 1974 ruling by Judge George Boldt. His decision upheld tribal, treaty-reserved rights and established the tribes as co-managers of the resource with the state of Washington.

Martinez ruled that our treaty-reserved right to harvest salmon also includes the right to have those salmon protected so they are available for harvest.

Our right is meaningless if there are no fish to harvest because their habitat has been destroyed. Today, we are losing the battle for salmon recovery because habitat is being lost faster than it can be restored.

The state argues that the treaties do not explicitly prohibit barrier culverts. But treaty rights don’t depend on fine print, they depend on what our ancestors were told and understood when the treaties were signed. They would never have understood or agreed that they were signing away the ability of salmon to get upstream.

The state claims that fixing its culverts is a waste because there are other barriers on the same streams and other habitat problems that need attention. But state biologists testified that passage barriers must be removed if salmon are to recover. State culverts are often located on the lower reaches of the rivers, and are the key to restoring whole watersheds.

Other road owners are doing their part. Under state law, timberland owners will fix all their barriers by this fall. Hundreds of other culverts have also been fixed. The state’s “you first” approach would mean no progress at all.

The state argues that a tribal victory would open a floodgate of litigation from the tribes on any state action that could harm fisheries.

But Judge Martinez ruled that the state’s duty to fix its culverts does not arise from a “broad environmental servitude,” but rather a “narrow and specific treaty-based duty that attaches when the state elects to block rather than bridge a salmon-bearing stream.”

During the Fish Wars of the 1960s and ’70s, tribal fishermen were arrested, beaten and jailed for exercising treaty-reserved rights. The beatings and arrests may have stopped, but the state has never stopped challenging tribal treaty rights, even though they have been upheld consistently by the courts.

Reserving the right to fish so that we can feed our families and preserve our culture was one of the tribes’ few conditions when we agreed to give up nearly all of the land that is today Western Washington. The treaties our ancestors signed have no expiration date and no escape clauses.

Northwest U.S. Treaty Tribes Fight Proposed Canada Oil Pipeline That Threatens Salish Sea

CHRIS JORDAN-BLOCH / EARTHJUSTICE

Representatives from four Northwest tribes argued against oil spill risks, destructive increases in oil tanker traffic, and threats to treaty-reserved fishing rights posed by project

Today’s arguments before Canada’s National Energy Board represent a critical and final call to safeguard the Salish Sea from increased oil tanker traffic and a greater risk of oil spills. Experts have acknowledged that a serious oil spill would devastate an already-stressed marine environment and likely lead to collapses in the remaining salmon stocks, further contamination of shellfish beds, and extinction of southern resident killer whales. If approved, the TransMountain Pipeline would instigate an almost seven-fold increase in oil tankers moving through the shared waters of the Salish Sea, paving way for a possible increase in groundings, accidents, and oil spills.

“We have a sacred duty to leave our future generations, our children, our children’s children, a healthy world,” said Mel Sheldon, Chairman of the Tulalip Tribes. “We will continue to oppose this project because it further threatens the Salish Sea with reckless increases in oil tanker traffic and increased risk of catastrophic oil spill.”

“Being Frank” More Salmon Habitat Protection Needed

By Lorraine Loomis, Chair, Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

We’ve seen some incredible salmon habitat restoration projects the past few years, but there’s a big difference between restoring habitat and protecting it. We must remember that restoration without protection does not lead us to recovery.

The Elwha River on the Olympic Peninsula continues to heal itself after the largest dam removal effort in U.S. history. Two dams on the river had blocked salmon migration and denied Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe’s treaty fishing rights for more than 100 years.

In another big project, the Tulalip Tribes and partners recently returned tidal flow to the 400-acre Qwuloolt Estuary. The estuary was drained and diked for farming in the early 1900s, blocking access to important salmon habitat.

Both were huge, costly projects that took decades of cooperation to accomplish. Every habitat restoration project – large or small – contributes to salmon recovery. But if we are going to achieve recovery, we must do an equally good job of protecting habitat, and that is not happening.

Treaty Indian tribes are seeking federal leadership to help turn this tide.

Salmon recovery efforts cross many federal, state and local jurisdictions, but it is the federal government that has both the legal and trust responsibility to recover salmon and honor tribal treaty-reserved rights. Through our Treaty Rights at Risk initiative, we are asking the federal government to lead a more coordinated and effective salmon recovery effort.

One way is to ensure that existing federal agency rules and regulations do not conflict with salmon recovery goals.

An example is the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ jurisdictional boundary they use for permitting shoreline modifications. The Corps regulates construction of docks and bulkheads in marine waters, and uses a high water mark based on an average of each day’s two high tides to determine its jurisdiction under the Clean Water Act.

But the Clean Water Act specifies the protection boundary should be the single highest point that an incoming tide can reach.

In Puget Sound, the Corps’ boundary is 1.5 to 2.5 feet below the highest tide. When you apply that to 2,000 miles tidelands, a large portion of important nearshore habitat is left unprotected.

That needs to change. We need to be protecting more habitat, not less.

Another example is agricultural easements issued by the federal Natural Resources Conservation Service that can block salmon habitat restoration efforts.

Federally funded agricultural easements pay landowners to lock in agricultural land uses permanently, regardless of whether those areas historically provided salmon habitat and need to be restored to support recovery.

The federal government needs to change the program to ensure agricultural easements do not restrict habitat restoration and other salmon recovery efforts.

These are just a couple of examples of how federal actions can conflict with salmon recovery goals to slow and sometimes stall our progress.

We know that habitat is the key to salmon recovery. That’s why we focus so much of our effort on restoring and protecting it. Many amazing restoration projects are being accomplished, but the more challenging task of protecting that habitat is falling short.

We must do everything we can to protect our remaining habitat as we work to restore even more. One way to do that is to harmonize federal actions and make certain they contribute effectively to recovering salmon, recognizing tribal treaty rights and protecting natural resources for everyone.

Tulalip turning tide on diminishing salmon

It has been 100 years since water flowed in this now former farmland along Ebey Slough. The place is unrecognizable from what it was just four months ago.

“A lot of things are going to change really fast in here,” said Todd Zackey, as he and a team of researchers from the Tulalip Tribes navigated the waters Monday.

In August, the Tulalip, along NOAA and Snohomish County breached a levee along the slough, flooding the land and returning its natural state.

Now, researchers are casting nets into the water to see what fish are showing up. The goal is to create a salmon spawning habitat to help in increase their numbers around Puget Sound.

(Photo: Eric Wilkinson / KING)

Right now, though, there are far more questions than answers.

“Can we punch a hole in the dike and have the salmon respond in a positive way?” asked researcher Matt Pouley. “Are we going to see a population response over a reasonable amount of time?”

So far only a few salmon have been spotted, but that’s to be expected for this time of the year. There are plenty of other fish, though, and that’s a good sign.

No one is in a hurry. This is a long term project. It will likely take a century for full restoration of these waters.

And this project is about more than strengthening the fish supply. It’s about a way of life that goes back thousands of years for the Tulalip, and preserving that tradition for generations to come.

“The tribe is, in essence, losing part of its culture,” said Zackey. “Restoring salmon is restoring the culture of the tribe.”

U.S. Should Honor Billy Frank’s Dream

“Being Frank”

By Lorraine Loomis, Chair Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

Billy Frank Jr., longtime chairman of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission, received many awards during his life and continues to be honored since his passing in 2014.

His life was celebrated last month when President Barack Obama posthumously awarded him the Medal of Freedom. It is the nation’s highest civilian award.

Billy would have been delighted to receive the medal, but even more delighted by the attention that such an award can bring to the issues he fought for every day: protection of tribal cultures, treaty rights and natural resources.

We hope the United States will honor not only Billy’s life, but also his dream, by taking action on the Treaty Rights at Risk initiative that was the focus of his efforts for the final four years of his life.

Salmon recovery efforts cross many federal, state and local jurisdictions, but leadership is lacking to implement recovery consistently across those lines. Billy believed that the federal government has a duty to step in and lead a more coordinated and effective salmon recovery effort. The federal government has both the legal and trust responsibility to honor our treaties and recover the salmon resource.

That’s why he called on tribal leadership to bring the Treaty Rights at Risk initiative to the White House in 2011. It is a call to action for the federal government to ensure that the promises made in the treaties are honored and that our treaty-reserved resources remain available for harvest.

Tribal cultures and economies in western Washington depend on salmon. But salmon are in a spiral to extinction because their habitat is being lost faster than it can be restored.

Some tribes have lost even their most basic ceremonial and subsistence fisheries – the cornerstone of tribal life. Four species of salmon in western Washington are listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act, some of them for more than a decade.

“As the salmon disappear, so do our tribal cultures and treaty rights. We are at a crossroads, and we are running out of time,” Billy wrote not long before his passing.

Over the past four years under the Treaty Rights at Risk initiative, we have met often with federal agency officials and others to work toward a coordinated set of salmon recovery goals and objectives. Progress has been slow, and at times discouraging, but we remain optimistic.

An important goal is to institutionalize the Treaty Rights at Risk initiative in the federal government through the White House Council on Native American Affairs, created by President Obama in 2013.

Economic development, health care, tribal justice systems, education and tribal natural resources are the five pillars of the council. With one exception – natural resources – subgroups have been created for each pillar to help frame the issues and begin work.

That needs to change. A natural resources subgroup is absolutely essential to address the needs of Indian people and the natural resources on which we depend. A natural resources subgroup would provide an avenue for tribes nationally to address the protection and management of the natural resources critical to their rights, cultures and economies.

We are running out of time to recover salmon and we are running out of time for the Obama Administration to provide lasting and meaningful protection of tribal rights and resources. Recent meetings with federal officials have been encouraging. We are hopeful that the natural resources subgroup will be created in the coming year.

The creation of a natural resources subgroup for the White House Council on Native American Affairs would truly be a high honor that the United States could bestow on Billy’s legacy.

Eight Tribes to Protest Coal Terminals During D.C. Conference

Leaders and members of the Lummi Nation and other Washington State tribes opposed to coal terminals in the Pacific Northwest are bringing their concerns to the other Washington, the U.S. capital, on Thursday November 5.

Eight tribes in total will call on Congress to honor treaties that safeguard both the environment and tribal members’ ability to fish and conduct other cultural and sustenance activities that would be compromised by proposed industrial development. They plan to speak on the issue at the Ronald Reagan Building courtyard during the White House Tribal Nations Summit, to be held

“Tribal treaty rights are being threatened by corporate interests and congressional interference,” said the tribes in a media release announcing the event. “As Lummi Nation fights to protect its fishing areas from North America’s largest coal terminal, other tribes have faced their own development pressures and stand united with Lummi against the terminal and the erosion of treaty rights.”

The Lummi have vociferously opposed the projects and have asked the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to review and reject the proposal for a coal rail terminal at Cherry Point, the ancestral village site of Xwe’chi’eXen.

RELATED: Lummi Nation Asks Army Corps to Deny Permit for Coal Export Terminal

The statement is signed by Lummi Nation Chair Tim Ballew II; Swinomish Indian Tribal Community Chair Brian Cladoosby (also president of the National Congress of American Indians, a post to which he was recently reelected); Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe Chair Frances Charles; Tulalip Nation Chair Melvin Sheldon Jr.; Yakima Nation Chair JoDe Goudy; Hoopa Valley Tribe Chair Ryan Jackson; Spokane Tribe Chair David Brown Eagle, and Quinault Tribe Vice President Tyson Johnston.

RELATED: Lummi Chairman: We Will Fight Coal Terminal ‘By All Means Necessary’

“Senator Steve Daines (R-MT) has led efforts in Congress to prevent the U.S. Army Corps from reviewing the impact of the terminal on the Lummi Nation’s treaty fishing rights—a central tenet of its trust responsibility,” the leaders said in the statement. “If successful, it could set a dangerous precedent for other projects in Indian country.”

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2015/11/03/eight-tribes-protest-coal-terminals-during-dc-conference-162304