BELLINGHAM, Wash. – Three summers ago the company that wants to build the largest coal export terminal in North America failed to obtain the environmental permits it needed before bulldozing more than four miles of roads and clearing more than nine acres of land, including some wetlands.

Pacific International Terminals also failed to meet a requirement to consult first with local Native American tribes, the Lummi and Nooksack tribes, about the potential archaeological impacts of the work. Sidestepping tribal consultation meant avoiding potential delays and roadblocks for the project’s development.

It also led to the disturbance of a site from which 3,000-year-old human remains had previously been removed—and where archeologists and tribal members suspect more are buried.

Pacific International Terminals and its parent corporation, SSA Marine, subsequently settled for copy.6 million for violations under the Clean Water Act.

According to company documents obtained by EarthFix after the lawsuit made them public, Pacific International Terminals drilled 37 boreholes throughout the site, ranging from 15 feet to 130 feet in depth, without following procedures required by the Army Corps of Engineers under the National Historic Preservation Act.

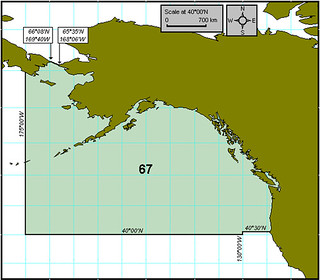

Map showing locations of 37 boreholes that Pacific International Terminals drilled at the proposed site of the Gateway Pacific Terminal.

(The original document the image is from, is available here.)

The Gateway Pacific Terminal is one of three coal export facilities proposed in Oregon and Washington. Mining and transportation interests want to move Wyoming and Montana coal by train so it can be loaded onto vessels on the Columbia River or Puget Sound and shipped to Asia.

The projects have been met with strong opposition from various groups concerned about increases in train and vessel traffic, coal dust and climate change.

The conflict between Gateway Pacific developers and the Lummi tribe underscores just how deep opposition can run among Native Americans whose homelands are in close proximity to proposed coal-shipping facilities. For tribes, the stakes include the protection of their treaty fishing rights and the sanctity of their ancestral burial grounds.

One of the boreholes at the Gateway Pacific site was drilled within an area designated as “site 45WH1,” the first documented archaeological site in Whatcom County, about 20 miles south of the Canadian border.

Boreholes are drilled to test the soil composition and geology of a site. In this case, the test was to help determine if the ground at Cherry Point could stand up to 48 million tons of coal moving over it each year.

Government regulators and tribal officials say they were unaware of Pacific International Terminals’ non-permitted work at Cherry Point until a local resident was out walking in the area, saw the activity, and reported it.

Pacific International Terminals said it was an accident. The company had planned to drill 36 more boreholes at the site before their activity was reported.

According to a document the company submitted to the Army Corps of Engineers four months prior to the non-permitted activities at the site, Pacific International Terminals knew the exact location of site 45WH1 and had said that “no direct impacts to site 45WH1 are anticipated as the project has been designed to avoid impacts within the site boundaries.”

In the document the company said that to mitigate potential impacts it would have an archaeologist on hand for any work done within 200 feet of site 45WH1. The company also acknowledged that it needed an “inadvertent discovery plan” in case human remains or other artifacts were uncovered, and that it would be required to consult with the Lummi tribe under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act before any work could begin at the site. Pacific International Terminals did none of those things.

“By going ahead and doing it illegally and then saying, ‘oh sorry,’ but actually having the data now, it allows them to start planning now,” said Knoll Lowney, one of the lawyers who represented the Bellingham-based environmental group RE Sources in its lawsuit against the terminal’s backers. “That way if they get their permits someday they’re ready to build right then.”

Pacific International Terminals and its parent company, SSA Marine, declined repeated requests for an interview; Bob Watters, senior vice president of SSA Marine, emailed this statement:

“We sincerely respect the Lummi way of life and … their cultural values. Claims that our project will disturb sacred burial sites are absolutely incorrect and fabricated by project opponents. We continue to believe we can come to an understanding with the Lummi Nation regarding the Gateway Pacific Terminal.”

Site 45WH1

Cherry Point and the waterways surrounding it are a culturally significant place for the Lummi Nation and other tribes. Ancestors of the Lummi peoples hunted, fished and buried their dead at Cherry Point for more than 3,000 years. And there is no shortage of archaeological evidence to prove it.

45WH1, a small section of Cherry Point, just 50 by 500 meters in size, is the most extensively studied archaeological site in Whatcom County. The location is not shared publicly because it is spiritually important to the tribe and they are afraid of people looting the site.

Western Washington University Faculty Herbert Taylor and Garland Grabert conducted seven separate field excavations at the site between 1954 and 1986.

Western Washington University Anthropology Professor Sarah Campbell. (Ashley Ahearn)

Both archaeologists have since died. Sarah Campbell, a professor of anthropology at Western Washington University, has studied the artifacts from 45WH1 since the late 1980s. It is a large collection, filling 150 boxes and includes harpoon points, shells, amulets, lip ornaments, reef net weights, beads, jewelry, blades and bone and rock tools, among other things.

Cherry Point is an area rich in potential for future research, Campbell says as she sorts through boxes filled with tiny plastic bags, each one labeled “45WH1.”

The area was used not only to hunt and fish, but also to manufacture reef net weights made of stone, which suggests permanent residence at the site. Campbell and others believe the site was used extensively over a long period of time, spanning from 3,500 years ago until relatively recently.

Arrow point found at site 45WH1. (Ashley Ahearn)

The Lummi signed a vast majority of their traditional land away in a treaty with the federal government in 1855. A portion of their traditional land known today as Cherry Point was taken at a later date; the tribe has disputed whether this was done lawfully. It is now owned by SSA Marine and Pacific International Terminals.

“That’s one of those things that makes Cherry Point important is it has a long time span,” she says. “And it provides the chance to see the changing use over time. The chance to do those comparisons through time is really important and useful.”

The Western Washington University collection also includes human remains, and Campbell believes that there are more Lummi ancestors buried at Cherry Point.

“It would be highly, highly, highly unlikely that there are not human remains in unexcavated areas of the site,” she cautions. “It’s absolutely prudent to assume that there are.”

‘My People’s Home’

From the deck of his fishing boat, the God’s Soldier, Lummi tribal council member Jay Julius looks to the shore of Cherry Point. He says that, for the Lummi, the spiritual and cultural value stretches far beyond the boundaries of site 45WH1.

“I see this as my people’s home. I can envision it,” Julius says quietly. “I know what’s there now.”

Reef net weights, carved from the rocks of Cherry Point. (Ashley Ahearn)

Julius cites Pacific International Terminals’ unpermitted activity at Cherry Point as a major source of tribal opposition to the Gateway Pacific Terminal.

“When I come out here, it’s all that’s on my mind—is what took place here at Cherry Point when these guys bulldozed over it and called it an accident,” he said. “It’s obvious. It doesn’t take a genius to figure it out.”

Despite the fact that the Lummi tribal council asserted its “unconditional and unequivocal” opposition to the Gateway Pacific Terminal in a letter it sent to the Army Corps of Engineers on July 30, the Lummi chose not to take part in the civil suit brought by RE Sources.

That, the group’s attorney Knoll Lowney said, would have strengthened the environmental group’s case against Pacific International Terminals and SSA Marine. The Lummi had standing in a civil court because they could have demonstrated that they were harmed, culturally and spiritually, by Pacific International Terminal’s unpermitted activity at Cherry Point.

“If they don’t take part in the legal process, they’re weakening themselves. They’re throwing away their weapons,” said Tom King, an expert on the National Historic Preservation Act who served on the staff of the federal Advisory Council For Historic Preservation in the 1980s.

The council oversees the permitting of projects that could affect places of historic and archaeological significance, like the Gateway Pacific Terminal.

It is unclear why the Lummi decided against participating in the environmental lawsuit. Diana Bob, attorney for the Lummi, declined to be interviewed for this story.

King said Pacific International Terminals’ non-permitted drilling and disturbance at Cherry Point could put approval of the Gateway Pacific Terminal at risk because the company skirted the requirements of the so-called “106 process” under the National Historic Preservation Act.

“I think the Lummi have a very strong case,” he said. “The site, the area, the landscape—they can show that it’s a very important cultural area and permitting the terminal to go in will have a devastating effect on the cultural value of that landscape.”

The Army Corps of Engineers is now working on finalizing what’s called a “memorandum of agreement” between Pacific International Terminals and the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. The Army Corps says the document, which was obtained by EarthFix and KUOW under the Freedom of Information Act, will serve as a retroactive permit.

The Lummi Nation refused to sign the memorandum or accept the $94,500 that was offered as mitigation.

For now, the coal terminal backers are being allowed to move ahead with the permitting process. But that doesn’t mean the larger questions have been resolved around how compatible a coal export terminal is at a location where local Native Americans have lived for millennia.

The tribe and historical preservation officials with the state and federal governments have written letters to the Army Corps objecting to its decision limiting the geographic area studied to determine the potential for damage to archeological resources at Cherry Point—another point of contention as the review continues.