By Michael Wines, The New York Times

The Interior Department opened the door on Thursday to the first searches in decades for oiland gas off the Atlantic coast, recommending that undersea seismic surveys proceed, though with a host of safeguards to shield marine life from much of their impact.

The recommendation is likely to be adopted after a period of public comment and over objections by environmental activists who say it will be ruinous for the climate and sea life alike.

The American Petroleum Institute called the recommendation a critical step toward bolstering the nation’s energy security, predicting that oil and gas production in the region could create 280,000 new jobs and generate $195 billion in private investment.

Activists were livid. Allowing exploration “could be a death sentence for many marine mammals, and is needlessly turning the Atlantic Ocean into a blast zone,” Jacqueline Savitz, a vice president at the conservation group Oceana, said in a statement on Thursday.

Oceana and other groups have campaigned for months against the Atlantic survey plans, citing Interior Department calculations that the intense noise of seismic exploration could kill and injure thousands of dolphins and whales.

But while the assessment released on Thursday repeats those estimates, it also largely dismisses them, stating that they employ multiple worst-case scenarios and ignore measures by humans and the mammals themselves to avoid harm.

Many marine scientists say the estimates of death and injury are at best seriously inflated. “There’s no argument that some of these sounds can harm animals, but it’s blown out of proportion,” Arthur N. Popper, who heads the University of Maryland’s laboratory of aquatic bioacoustics, said in an interview. “It’s the Flipper syndrome, or ‘Free Willy.’ ”

How the noise affects sea mammals’ behavior in the long term — an issue about which little is known — is a much greater concern, he said.

A formal decision to proceed with surveys would reopen a swath off the East Coast stretching from Delaware to Cape Canaveral, Fla., that has been closed to petroleum exploration since the early 1980s.

Actual drilling of test wells could not begin until a White House ban on production in the Atlantic expires in 2017, and even then, only after the government agrees to lease ocean tracts to oil companies, an issue officials have barely begun to study.

The petroleum industry has sunk 51 wells off the East Coast — none of them successful enough to begin production — in decades past. But the Interior Department said in 2011 that 3.3 billion barrels of recoverable oil and 312 trillion cubic feet of natural gas could lie in the exploration area, and nine companies have already applied for permits to begin surveys.

President Obama committed in 2010 to allowing oil and gas surveys along the same stretch of the Atlantic, and the government had planned to lease tracts off the Virginia coast for exploration in 2011. But those plans collapsed after the Deepwater Horizon oil rig disaster in April 2010, and the government later banned activity in the area until 2017.

Thirty-four species of whales and dolphins, including six endangered whales, live in the survey area. Environmental activists say seismic exploration could deeply imperil blue and humpback whales as well as the North American right whale, which numbers in the hundreds.

Surveys generally use compressed-air guns that produce repeated bursts of sound as loud as a howitzer, often for weeks or months on end. The Interior Department’s estimate said that up to 27,000 dolphins and 4,600 whales could die or be injured annually during exploration periods, and that three million more would suffer various behavioral changes.

But many scientists say death and injury are not a major concern. Decades of seismic exploration worldwide have yet to yield a confirmed whale death, the government says.

“It is quite unlikely that most sounds, in realistic scenarios, will directly cause injury or mortality to marine mammals,” Brandon Southall, perhaps the best-known expert on the issue, wrote in an email exchange. “Most of the issues now really have to do with what are the sublethal effects — what are the changes in behavior that may happen.” Dr. Southall is president ofSEA Incorporated, an environmental consultancy in Santa Cruz, Calif.

Loud sounds like seismic blasts appear to cause stress to marine mammals, just as they do to humans. Experts say seismic exploration could alter feeding and mating habits, for example, or simply drown out whales’ and dolphins’ efforts to communicate or find one another. But the true impact has yet to be measured; there is no easy way to gauge the long-term effect of sound on animals that are constantly moving.

“These animals are living for decades, if not centuries,” said Aaron Rice, the director of Cornell University’s bioacoustics research program. “The responses you see are not going to manifest themselves in hours or days or weeks. We’re largely speculating as to what the consequences will be. But in my mind, the absence of data doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem.”

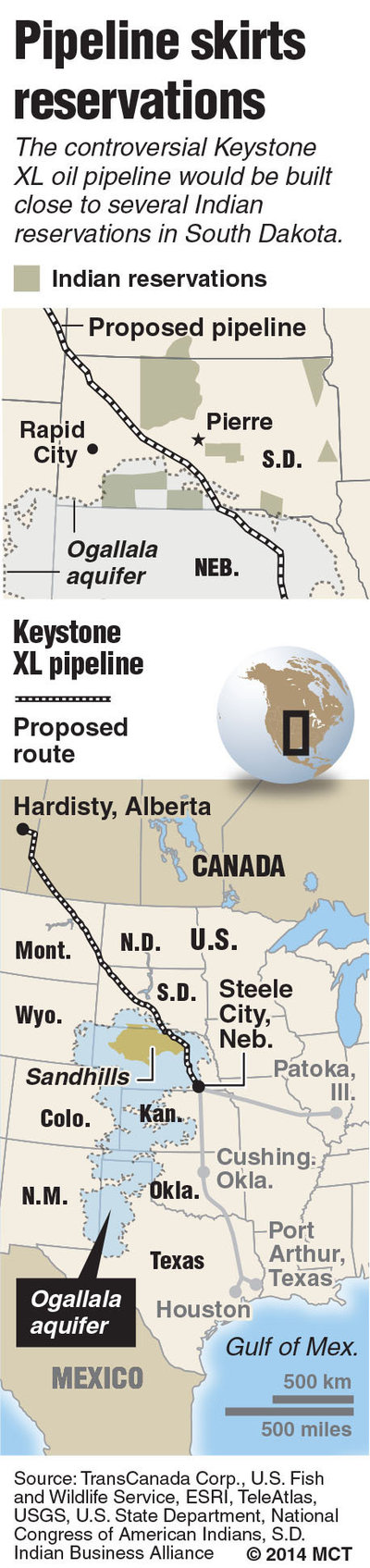

“If you like to drink water, if you like your children not being harmed, if you don’t want your women being harmed, then say no to the pipeline,” Grey Cloud said. “Because once it comes, it’s going to destruct everything.”

“If you like to drink water, if you like your children not being harmed, if you don’t want your women being harmed, then say no to the pipeline,” Grey Cloud said. “Because once it comes, it’s going to destruct everything.”