By Tony Schick, OPB

The Wyoming Governor invited 25 members of eight Northwest tribes on an all-expenses paid tour of coal operations.

The tour happened last week, and only one tribe participated.

The Wyoming government hosted three visitors from the Pacific Northwest, according to the Casper Star-Tribune: Alice Dietz of the Cowlitz Economic Development Council, Gary Archer of the Kelso, Washington, City Council and Gary MacWilliams of the Nooksack Tribe.

The tour was the latest in the Wyoming government’s efforts to promote coal as good for the economy and not as environmentally dirty as its critics in the Northwest might think. The governor and representatives of the Wyoming Infrastructure Authority have also visited proposed sites for coal export facilities in the Northwest.

With more coal in the ground than the U.S. needs or wants, particularly in light of new clean air regulations that phase out coal plants, the future of the Powder River Basin’s coal industry depends on exports. Several projects have been proposed in Oregon and Washington to receive coal from Montana and Wyoming by rail, transfer it to ships and send it to Asia.

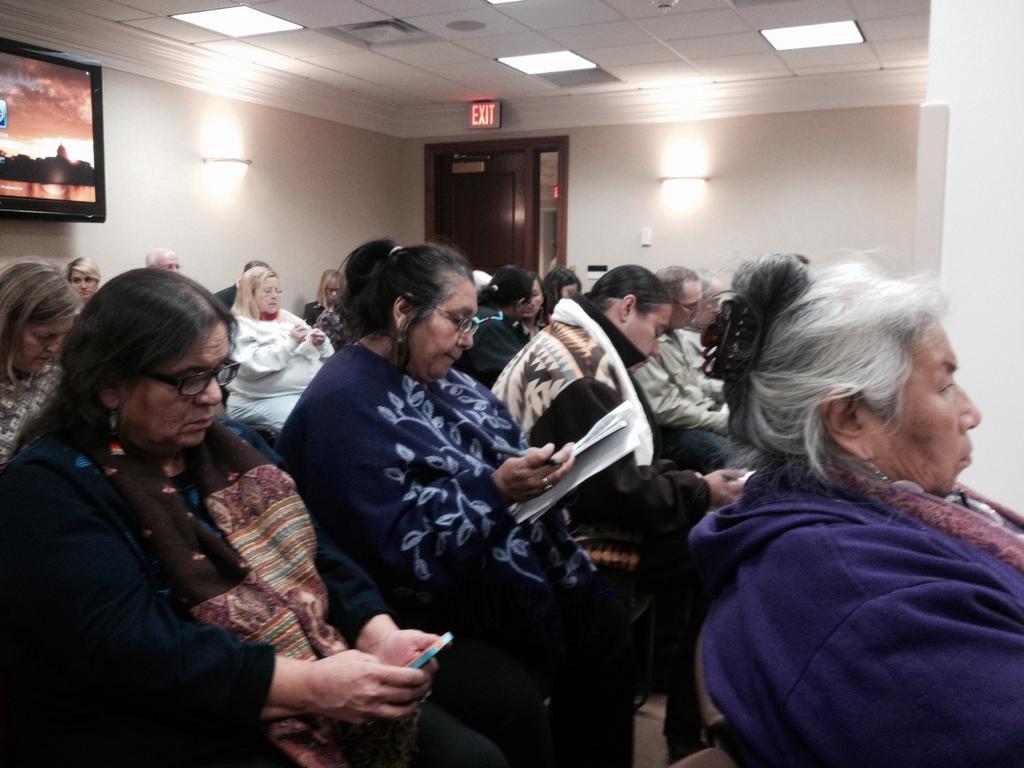

Most tribes in Oregon and Washington oppose coal exports, in part because of concerns about what coal dust and marine shipping would mean for their tribal fishing grounds. Tribes’ treaty fishing rights give them unique power to halt coal export projects.

Most refused the offer, and the tour itself didn’t appear to change any minds. Those who attended were either already in favor of coal exports or remained unswayed. But it was impressive to some. Here’s a quote from the Star-Tribune article:

“We had a prime rib dinner last night,” marveled Gary Archer, a city councilman from Kelso, Washington, a town neighboring one of the proposed ports. “These guys got it made up here. They got everything they need, except public perception.”

Coincidentally, the tour happened the same week the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued its starkest warning yet, essentially saying if we’re going to have a shot at curbing climate change, the fossil fuels currently in the ground need to stay there.