Hands on training in the latest hair, skin, nail and beauty techniques

Category: Education

Education Chasing The Elusive ‘Quality’ In Online Education

Getty Images, Hulton Archive

By: NPR

Jeff Hellmer is an accomplished jazz pianist who has taught music at the University of Texas at Austin for 27 years. He thinks of himself as more than a teacher, though: “What I would like to do with my teaching is be an ambassador for jazz.”

This past spring, in what’s become an increasingly common move, he brought his ambassadorship to a wider audience. He turned his popular introductory course, Jazz Appreciation, into a free 10-week online course.

It’s open to anyone on through a company called edX, and 19,000 people signed up.

Online college is no longer the future. It’s here. According to the Sloan Consortium, more than one-third of all U.S. college students now take at least one course online for credit. That’s 7 million students last year alone. Meanwhile, on platforms like edX (over 2 million users) and Coursera (over 8 million users), people from every country in the world are taking free versions of college courses.

And Starbucks just announced that it will offer over 100,000 employees the chance to take college classes online from Arizona State University.

The news from Starbucks, amid this dramatic expansion of online learning, has reignited a long-running debate about the quality of what’s being offered.

In other words, can 19,000 students, watching a video of Jeff Hellmer on their computer screens, ever hope to learn as much – or learn as well – as the students who’ve sat in a classroom right in front of him for all those years?

To answer that, we need to define and measure “quality” in online education. Which is tricky, because we don’t have a great definition of quality in face-to-face education.

Fortunes—not to mention the education that millions of students will receive —ride in the balance.

The Problem

There’s reason to be cautious.

A meta-analysis by the U.S. Department of Education in 2010 showed that students performed modestly better in courses with some online component.

However, a more recent study from Columbia University, focusing specifically on community college students, shows that college students are more likely to withdraw from online courses, that they score lower in these courses when they do finish, and that those who begin college with online courses are less likely to persist and complete their degrees.

The study also found that online courses tend to widen the achievement gap: African-Americans, and those with lower previous grades, do worse in an online environment.

The Columbia researchers, as well as other critics, argue that the reason students so often fail in these classes is because of the way the instruction is designed.

Most online courses, including Massive Open Online Courses, or MOOCs, consist of video snippets of lectures, readings, and multiple-choice quizzes. There’s usually some kind of online forum or discussion page for students to talk over the concepts presented in the course.

Basically, it’s copying the traditional classroom lecture format into the online realm.

The main strength of this approach as that it can be done almost free. That’s exactly what gets people so excited about online education in general, and MOOCs in particular.

Anant Agarwal, the founder of edX, likewise, told me in a recent interview that giving millions around the world of people access to higher education is a key goal of the initiative, which is backed by MIT and Harvard. He makes a comparison to basic infrastructure. “We are building free broad gauge railroad around the world,” he says. “You can think of the content as the carriages.”

The metaphor—comparing the distribution of knowledge with the distribution of, say, coal or sugar—is one that troubles many critics of educational technology.

“Is education content delivery? Is it the same as putting resources online?” asks Audrey Watters, an author and blogger. “We’re starting to frame teaching and learning in terms of language we use to talk about the web and media: ‘content delivery platforms’ and ‘learning management systems.’ “

Instead of the oft-maligned “factory model” of education, she says, what you end up with instead is a “cubicle model”—one person with a laptop, shoveling in information.

Adaptive Learning

There are attempts to use new technology to make online learning more interactive. Some of these efforts show promise – especially in the area of reaching remedial students.

At the University of Texas, Jeff Hellmer partnered with a company called Cerego to translate some of the material he covers in the jazz course into a set of what are often called “adaptive learning” items.

Andrew Smith Lewis, cofounder of Cerego, calls his company’s technology “flashcards on steroids.”

Hellmer created 180 items covering historical facts, technical elements of jazz music, and music clips where the student would have to listen and name the title, artist, and era.

For example, a picture of Art Blakely requires a student to identify the ‘Hard Bop,” era. Or they listen to a snippet of ‘Kind of Blue’ and must answer ‘Miles Davis.’ As you go through the set, the system is predicting how well you know each item, based on how many times you’ve seen it, how recently you’ve seen it, and how often you’ve seen it.

(Here is the full set if you want to test yourself).

Cerego uses an artificial intelligence algorithm, based in part on the science of memory, to decide which item to show you next, and when to show you the same item again. The goal is that you memorize them in an optimal amount of time. The program is also designed to get students to retain the information longer than with traditional methods. You have to identify each item correctly multiple times instead of just cramming to get it right one day on one quiz.

A central feature of adaptive learning is that it varies the presentation of content according to the user’s responses.

The secret sauce of this system? It’s kind of fun, like a video game.

“The mechanics of a successful game are designed to keep you in this band between boredom and frustration,” says Cerego’s Smith Lewis. “We see a nice uptick in engagement and completion.”

The thinking is that students are more likely to stick with Cerego-enhanced courses because it was a thrill to challenge themselves with the flashcard tool.

Millions of students from kindergarten through college are currently using adaptive learning software, both in online-only and blended settings.

Among the most popular are Pearson’s MyMathLab, with 10 million college students, Scholastic’s Math 180, Dreambox Learning, and Khan Academy. Math is the most common subject being taught this way, but the programs can cover any topic with a set of facts to be absorbed.

A leader in these efforts is Arizona State University, which has gone farther than any other large university to bake these concepts into online courses from the get-go.

The university has partnered with Pearson and a company called Knewton since 2011 on dozens of courses. ASU officials say they’ve had especially positive results with their developmental math courses—the exact same type of course that the Columbia University researchers found online students were doing worse in.

Bean-counting

”Quality” in online education is about more than enhancing content delivery or adding multimedia bells and whistles.

The technology makes it possible to measure student outcomes in unprecedented detail. This is affecting the way we think about quality in all of education.

There’s a wealth of data available, for example, from Jeff Hellmer’s Jazz Appreciation course.

Students on average memorized the basic facts in just 11 hours, using Cerego. And of the more than 20,000 who signed up initially, 2,370 actually passed. That’s a 12 percent pass rate—compared to the 5 percent typical for most MOOCs.

Two-thirds of those who finished did so with a grade over 90 percent. Three-fourths of students agreed that using Cerego’s adaptive learning tools helped them learn the material faster, which the company’s research shows is true in other subjects.

That level of data collection could enable schools to move beyond the traditional definition of quality in higher education, based on selectivity and scarcity. Historically, “top students” got into the most expensive colleges, and that made them “top schools.”

But most students attend public universities and community colleges that accept the vast majority of the students who apply. Therefore selectivity doesn’t apply broadly as a measure of quality. And so, colleges in this sector, with the enthusiastic support of the federal government, are developing new, data-driven measures of quality based on student outcomes, like transfer, graduation, and employment rates.

Arizona State University is a case in point. It’s a giant public institution with over 75,000 students, that accepts 90 percent of those who apply.

In recent years the university has become preoccupied with improving outcomes. Their six-year graduation rate is now at 58.7 percent, compared to a national average of 59 percent (but just 31 percent for open-admission schools like ASU). This is trending up: the number of degrees awarded has increased 60 percent since 2002.

In part, ASU is relying on technology, like an online advising system called eAdvisor, to improve student success. The system helps students navigate the university’s 290 majors and map out the courses they need to reach their goals. ASU Online launched in 2006. President Michael Crow’s vision is to grow online enrollment to 100,000 students. The recent deal with Starbucks is part of that effort.

On some key measures ASU’s current 10,000 online-only students seem to be doing worse than on-campus students: the 3-year graduation rate is just 36 percent (most online students come into the program with some college credits already, which is why they report three-year rates). This jibes with what we see in many online programs.

The Blend

In this drive to define – and achieve – “quality” in online education, as in traditional education, research points to one essential element: interaction with instructors.

It doesn’t have to be face to face. Video chats, phone calls, email and even text messages can all help students stay engaged and motivated. Group work and peer discussions are important too.

But instructor time remains the most expensive resource, and it’s often scarce and rationed, especially in the online realm.

Smith Lewis, along with other ed-tech people I talked to, framed the next generation of computer enhanced learning as a way to free up professors to do what they do best—not to replace them.

Professor Hellmer, for one, was so taken with the Cerego platform that he decided to incorporate it into his live, in-person classes, starting this summer. He sees it as a labor-saving device: the machine will handle the shoveling in of facts, while he does the cultivating of the students’ mental gardens.

“The part I’m looking forward to is spending more time discussing more complicated issues or higher-level thinking,” he said. “I’m hoping that Cerego is going to take care of that foundational learning more efficiently.”

He says the Cerego content will make up “about half” of the grade in the class. Instead of taking quizzes where they might just be guessing the right answer, students will have to study until they get a certain percentage of items into the “green zone” on the Cerego system, meaning the computer is convinced they have seen, repeated, and squirreled these facts away in their brains for the long haul. And not for nothing, those are quizzes that Hellmer and his assistants no longer have to grade.

Anant Agarwal, the founder of the MOOC platform edX, sees many professors making this transition, taking something they’ve developed online back into the traditional classroom setting. Universities are repurposing their own MOOCs on campuses in a variety of ways, as well as adapting the resources produced by others.

In the end, the vision of “quality” in higher education will probably take in a little bit that’s old, and a little bit that’s new.

Hibulb Cultural Center Film Series, Sunday June 29

TERO Construction Training Center first of its kind: First graduating class to receive state pre-apprenticeship credentials

By Andrew Gobin, Tulalip News

TULALIP – Tulalip TERO celebrated the first graduating class of the new TERO Construction Training Center June 12. Students graduating at the TCTC celebratory lunch showcased their final projects. Tribal leaders, program staff, former staff, and students shared words about what the day meant.

“What you’re doing here is building a foundation for your careers,” began Tim Wilson, a program manager for the Department of Labor and Industry. “There is nothing in this world you can’t do if you put your mind to it. This foundation you’ve built will help in that.”

Wilson congratulated the students, and honored them and staff for the work to make the TCTC program a successful reality.

“I was on the phone the other day, talking to someone back in D.C., and we were discussing national issues and apprenticeship. I was able to say, ‘Well guess what. I’ve got the first tribal pre-apprenticeship program,’ and there was silence on the line,” he said.

Tulalip’s new TCTC program is the first state recognized pre-apprenticeship program fully operated by a tribal entity. Washington State Labor Board categorized it as a “pre-apprentice” program , whose graduates are qualified to join various trade unions and their respective apprenticeship programs. Upon completion of the coursework students are ready to safely enter the construction work environment.

“This program is a learning opportunity for our members and other Native Americans. It gives our people a chance to learn a trade and contribute to the building of our community. Many of the program’s graduates go on to full employment with our tribal construction department, or with one of the many construction companies in the region,” said Tulalip Tribes Chairman Herman Williams. “We’re very proud of those who have completed the first year of our newly recognized pre-apprentice program.”

The Tulalip Construction Training program has been in existence for over a decade and over the years has been managed by both the Tulalip College Center and The Tribal Employment Rights Office (TERO) and has also been funded by different grants. This past year it reverted to TERO management and with the change has come a shift in emphasis from simply providing the vocational training program to advocating and helping with job placement after students complete the program and exposuring students to the various trades through speakers from trade unions and representatives from certification programs. If students choose to stick with the trades as a career pathway they can expect to make a good living.

The Tulalip Tribes operates the TCTC in partnership with Edmonds Community College, offering training in the construction trades to its members, as well as other Native Americans, in order to help them obtain the necessary skills to enter the job market

“Edmonds Community College is proud to be a partner with the Tulalip Tribes in providing this opportunity for students to acquire job-ready skills in the Construction Industry Training program,” said Andy Williams from the Edmonds Community College business program. “Many of the graduates earn employment in the construction trades upon graduation, earning good wages and contributing to the economy and the community. This is a great educational model initiated by the Tulalip Tribes, and Edmonds Community College is honored to participate.”

TERO program staff, past and present, could not be more proud of their students, honoring the work they were able to accomplish.

The ten week course provides students instruction in the basics of the construction trade. Students are also awarded a flagging certification, First AID/CPR, and an OSHA 10 Hour Safety Card. In addition to these necessary construction skills, at the Tulalip TCTC students learn a set of values to guide and drive them towards successful careers.

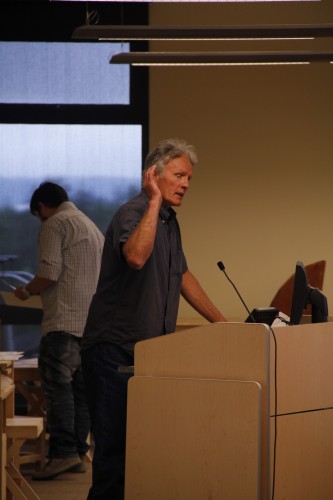

Photo: Andrew Gobin/Tulalip News

Mark Newland one of the instructors for the program, has worked with TERO for many years, formerly with the NACTEP program, offered some final words of guidance to his students. “I don’t worry about my reputation, I worry about my character. Because if you take care of your character, your reputation will take care of itself.”

Newland was praised for his dedication to the program, called “the soul of this organization, and a great role model.”

He talked about the pride the students should feel not only about the work they’ve done for themselves, but what it means for years to come, saying, “One of the great things about being a carpenter is, for the next 20 years, you will drive by a project and be able to say to yourself, ‘Hey…I did that.’ That is something to be proud of.”

Andrew Gobin is a staff reporter with the Tulalip News See-Yaht-Sub, a publication of the Tulalip Tribes Communications Department.

Email: agobin@tulalipnews.com

Phone: (360) 716.4188

This Is Who I Am: Coeur d’Alene Students Show Cultural Pride With Video

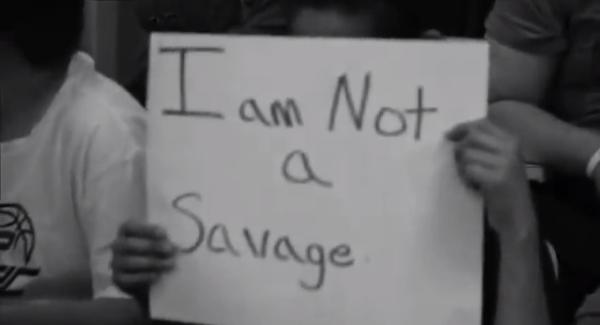

An inspirational video featuring Native American youth from this year’s Leadership Development Camp shows viewers who the youth are and who they are not—mascots, savages, alcoholics, drug addicts.

A black and white silent portion of the video has students each holding up a sign saying what they are not, like “I am not a mascot,” and “I am not a savage.” The students are then seen in color and explaining what they are—beautiful, a basketball player, a dreamer, a leader, the next cultural generation.

“We’re proud of our culture and never will ever hide it,” one of the students in the video says.

The Leadership Development Camp is designed for youth ages 13 to 17 from the Coeur d’Alene Reservation. Its goal is to develop leadership skills, resiliency, and strengthen academic skills.

The camp brings the students to the Washington State University Pullman campus for a week-long stay.

“Through participation in team building and sports activities and culturally responsive specialized academic seminars, this one-week residential camp offers students a chance to develop new skills, experience college life, and reflect upon and prepare to meet their goals for the future,” says information with the video.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/06/26/who-i-am-coeur-dalene-students-show-cultural-pride-video-155445

5 Ways to Make Gardening With Kids Easy and Educational

It’s no secret that kids who help plant a garden are more likely to want to eat the fruits and vegetables that it produces—and growing a garden is a great way to get your kids interested in trying unfamiliar foods.

RELATED: 5 Easy Steps: How to Start a Community Garden

Whether you’re thinking of spearheading a school garden, you’ve got a plot in the community garden or you’re blessed to have a couple of raised beds in your own back yard, here are five tips for making gardening fun, easy and rewarding for your little ones:

1. Center the Garden on the Kids

Involve the kids in deciding what to plant and where to plant it. Use this as an opportunity to teach them about the balance between sunlight and shade, and even to help them learn to track to the path of the sun. You could even experiment and plant the same kind of plant or seed in three different locations with varying access to sunlight and water. Ask your children to observe the differences in the plants as they grow.

2. Designate a Specific Area for Their Gardening

If you’ve got your own ambitions for gardening it would be wise to designate a special bed or section of a bed specifically for the children to garden. This will keep them from over “helping” you and encourage them to take ownership over their own space. It may be a good idea to buy them their own gardening tools as well. Even simple plastic tools for playing in the sand could work well in a kiddie garden.

3. Make the Garden Interactive

Plant flowers that attract butterflies and hummingbirds and perhaps even encourage a cutting garden so that the kids can touch and smell the flowers. Release ladybugs into the garden and track their life cycle. Take photos of a favorite plant or vegetable once a week to track its growth. My favorite idea? Plant a sunflower house. Simply plant sunflower seeds or starts in a large circle, leaving enough space between two of the sunflowers for children to easily pass through without damaging the flowers. By the end of the summer the sunflowers will have grown up into a large round “house” with a gaping door—a perfectly shaded playhouse for the dog days of summer.

4. Keep it Simple

Your kids are likely to be more interested in the garden if they begin to see results sooner rather than later. Be sure to plant vegetables that grow quickly, like radishes, alongside more tantalizing varieties that will prove to be worth the wait, such as cherry tomatoes or sweet peas. Forgo seeds for starts to speed the “fruits of our labor” process up a bit more and don’t forget to plant herbs, which are ready to eat almost immediately.

5. Don’t Stop at the Garden

Use the garden as a resource and an excuse to get your kids in the kitchen all summer long too. Teach them how to cook and prepare delicious meals with the vegetables and herbs that they grew—even set the dinner table with a bouquet of fresh flowers from the garden as well. Begin to teach them delicious and simple food pairings, like fresh basil with tomato. If they’re old enough challenge them to find a new recipe once a week, whether they scour the web, your cookbooks or their imagination.

Happy Gardening!

Darla Antoine is an enrolled member of the Okanagan Indian Band in British Columbia and grew up in Eastern Washington State. For three years, she worked as a newspaper reporter in the Midwest, reporting on issues relevant to the Native and Hispanic communities, and most recently served as a producer for Native America Calling. In 2011, she moved to Costa Rica, where she currently lives with her husband and their infant son. She lives on an organic and sustainable farm in the “cloud forest”—the highlands of Costa Rica, 9,000 feet above sea level. Due to the high elevation, the conditions for farming and gardening are similar to that of the Pacific Northwest—cold and rainy for most of the year with a short growing season. Antoine has an herb garden, green house, a bee hive, cows, a goat, and two trout ponds stocked with hundreds of rainbow trout.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/06/23/5-ways-make-gardening-kids-easy-and-educational-155354

Children can’t be what they can’t see

Speakers encourage and honor students at annual graduation banquet

By Andrew Gobin, Tulalip News

TULALIP – The Tulalip Tribes honored all tribal members that graduated this year, as well as all other Native students who graduated from the Marysville School District, on June 13 at the Tulalip Resort. Ninety nine students graduated from high school and post-secondary education. Tribal leaders recognized the academic achievement of the students, and former Chair of the National Indian Gaming Commission, Tracie Stevens, gave an inspirational keynote speech. Student speakers expressed gratitude for many years of support, telling of their struggles and achievements.

Leticia Bumatay of the Shool Home Partnership Program (SHOPP) said, “Seven years ago, I couldn’t see myself standing here. I say seven years because that was when I lost my mom. I was bounced around with beda?chelh, so I am 21 years old getting my high school diploma today. The one thing I have to tell everybody is to never give up. Never give up on what your dreams are, never give up on your hope, and never give up on your faith. My grandma taught me that.”

Tulalip Treasurer Glen Gobin encouraged graduates to go out and see the world without the fear of losing their roots.

“You graduates here today, your whole world is out there. You can get an education or you can go to work. But one thing I just want to encourage you all, because it’s the one things that has kept us who we are today, is stay grounded in your culture, stay grounded in who you are, stay grounded and come back and help your tribe, because that what our past people have done,” he said.

Keynote speaker Tracie Stevens took the stage, introducing herself in a traditional manner. She highlighted the importance of education, and what that empowers students to accomplish for their tribe and for themselves.

“I didn’t understand what the purpose of education was, and what it would do for me later in life. I was the first person in my immediate family to graduate high school and began a 21 year journey to get a four-year degree. I worked for Tulalip from 1995 to 2009. I just decided to finish school one day. I figured out that if I went to school, at night, full time, I could finish in one year what I had been trying to for the last 20 years. I was the first in my family to get a four-year degree. The lack of a question I had when I was younger, about what education would do for me; I found later that education would expand my universe, a great deal. Which eventually led to my passion, this policy nerd that I am, which is helping my people, in any way that I could.”

Education is a journey for finding passion. In high school, some students dare to move on to college to chase their life’s passion. Others find their passion in jobs or job training. It’s all about doing what you love in the long run.

Mekalani Echevarria of Marysville Getchell High School said, “Find a passion and go with it. Life without passion is utterly boring. But don’t forget where you come from. Remember your teachings from elders and use them in daily life. Stay humble, respectful, and honest.”

Tulalip graduates were recognized for the example they are for their people.

“What kind of auntie would I be if I didn’t graduate. I had to be an example for my nieces and nephews. Not only for them, for the next generation,” said Tulalip Heritage High School graduate Santana Shopbell.

That need to be an example continues on long after graduation. Stevens talked about how she struggled with the choice of accepting the nomination to chair the National Indian Gaming Comission, knowing it would extend her time away from home.

“A woman I worked with, Rene Stone, told me, ‘How will all those Indian boys and girls, that are growing up now, ever know that they can come this far and do this kind of work if they don’t see you out front leading? Children can’t be what they can’t see,’” Stevens recalled. “You all have reached an important benchmark, and with that you are breaking a cycle of an old failed Indian Education policy that was meant to take the Indian out of you. We can do more than just survive, we can thrive and prosper. You’ll use your education, your knowledge, to pass that on to the next generation, to change the history of Indian Education so that we control our own destiny. Be the example, be the change, and be the one that passes that on.”

Ninety nine graduates this year. Ninety nine examples of hard work and dedication. Ninety nine examples of success and achievement, overcoming adversity in so many ways. Congratulation to all graduates of 2014.

Andrew Gobin is a staff reporter with the Tulalip News See-Yaht-Sub, a publication of the Tulalip Tribes Communications Department.

Email: agobin@tulalipnews.com

Phone: (360) 716.4188

Academics, Behavior, Culture help school improve test scores

By Steve Powell, Marysville Globe

MARYSVILLE – In an effort to improve state test scores, two local schools are concentrating on their ABC’s.

Not the alphabet; it’s not that simple. They are focusing on Academics, Behavior and Culture.

Quil Ceda and Tulalip elementary schools have been labeled a Required Action District because of lower-than-required state test scores. This new state RAD funding replaces extra federal funding the schools have received for three years.

“Three years is not enough time to turn around a school,” said Kristin DeWitte, who along with Anthony Craig are principals at the now-combined schools.

DeWitte said because these programs are fairly new, there is no book of directions.

“It’s like building an airplane while flying it,” she said.

She said some schools that didn’t make the grade have tried to “score bump” so they would look better on the state tests. She and Craig decided not to do that because it wouldn’t represent lasting change.

So, instead of focusing on the third- through sixth-graders who take the test, their schools started working with kindergarteners.

“That will be best in the long run,” she said.

DeWitte said the plan has worked, as their youngest students went from the bottom of the Marysville School District in scores to the top.

The change has come about because of targeted instruction. Individual plans are made for each student. Small groups are formed to give students the special instruction they need.

Craig said the systematic approach has benefitted the teachers, too.

“We have trouble retaining teachers,” he said, but the new teachers are excited about the direction.

“With the collaboration they feel valued and listened to,” he said. “There’s an openness to figure things out.”

Teachers work together on strategies and lessons and even watch each other teach.

“There’s no ‘my secret lesson.’ They all share,” DeWitte said.

Despite the extra funding, state scores are still down for the schools, except for science. But the true results of the effort will come when the former kindergarteners start taking the tests when they reach third grade.

Meanwhile, Marysville School District board members showed support for the schools at a recent meeting.

While Craig got choked up by the support from staff, the district president became downright upset.

“Institutional racism,” is what school district President Tom Albright called it.

Albright spoke out because only three other schools in the state have reached RAD status, and all are “historically underserved with students of color,” Craig said.

Albright said the state is singling the schools out in a negative way instead of taking responsibility for not helping them in the past.

Craig got emotional when he looked into the packed house at the board meeting May 19 and saw many of his teachers. He has been with the district since 1999 and is in his third year as principal.

I’ve always wanted a quality team out there, and “we have them now – top-notch teachers,” he said.

Assistant Superintendent Ray Houser said the two schools already are improving their test scores.

“This is all about the achievement gap,” he said. “We are just not quite closing the gap quickly enough.”

As a result of test scores, the district underwent an academic audit and wrote a school improvement plan.

Under RAD, it will get extra funding for three more years.

Craig said the district is focusing on academics, behavior and culture. He said leadership at all levels also is a priority.

“Everyone owns a piece of the success,” he said.

Craig said he wished there was a book he could get to find out how schools like his can improve, but “it’s something we don’t know yet.”

School board members applauded the effort.

“Maybe when we’re done we can write the book,” director Pete Lundberg said. “No one else is doing this work at this level. This is nothing short of heroic.”

Lundberg said the improvement plan values culture, teaches culture and values how decisions are made.

“It’s truly a community effort,” he said.

Member Chris Nation added: “Everyone took an active role and created an environment where all can excel. That’s not the way it used to be.”

Nation said just looking at the test scores can make a school look bad.

“But this is far beyond what other schools have done,” Nation said.

Learn how to start your own business, July 29

Senate Hearing Today Will Examine Higher Education for Indians

Source: Department of Education, June 11, 2014

Jamienne Studley, U.S. deputy under secretary of education, will testify today before the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs as part of an oversight hearing entitled, “Indian Education Series: Examining Higher Education for American Indian Students.”

Studley will discuss the U.S. Education Department’s efforts to expand educational opportunities and improve educational outcomes for Native American students through college access, affordability and completion. The administration remains committed to working with tribes and supporting tribal colleges and universities to ensure that all American Indian and Alaskan Native students have high-quality educational experiences that prepare them for careers and productive lives.

The administration views college completion as an economic necessity and a moral imperative. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, while the average public high school graduation rate for all students has increased six points, from approximately 75 percent in 2007-08 to 81 percent in 2011-12, the high school graduation rate for American Indian/Alaskan Native students over the same period rose by only four points, from 64 to 68 percent.

To find out more about the Department’s efforts to make college more accessible, affordable and high-quality, click here.

In addition, President Barack Obama’s Opportunity for All: My Brother’s Keeper Blueprint for Action report was released recently, outlining a set of initial recommendations and a blueprint for action by government, business, non-profit, philanthropic, faith and community partners to expand opportunities for boys and young men of color—including American Indians and Alaskan Natives—to help them stay on track and reach their potential.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/06/11/senate-hearing-today-will-examine-higher-education-indians-155247