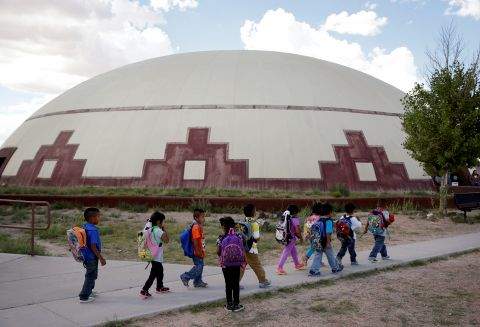

Toas-Pueblo-InterTribal-Buffalo-Council-School-Lunches: This little guy at Taos Pueblo really enjoyed his buffalo dish and ate most of his salad, too. Taos is one of the schools included in the ANA grant awarded to the InterTribal Buffalo Council.

New guidelines for the National School Lunch Program are aimed at providing the nation’s children with healthy, age-appropriate meals in an effort to reduce childhood obesity and improve the overall well-being of kids, especially poor kids, across the country.

A Matter of National Security

The federal government established the school lunch program in the early 1930s to try to prevent widespread childhood malnutrition during the Depression and to support struggling farmers by having the federal government buy up surplus commodity foods. By 1942, 454 million pounds of surplus food was distributed to 93,000 schools for lunch programs that benefited 6 million children.

But when the U.S. joined World War II, the U.S. Armed Forces needed all of the surplus food U.S. farmers were producing. By April 1944, only 34,064 schools were participating in the school lunch program and the number of children being served had dropped to 5 million.

In the spring of 1945, Gen. Lewis B. Hershey, a former school principal, told the House Agriculture Committee that as many as 40 percent of rejected draftees had been turned away owing to poor diets. “Whether we are going to have war or not, I do think that we have got to have health if we are going to survive,” he testified. Within a year, Congress passed legislation to appropriate money to support the program on a year-by-year basis and by April 1946, the program had expanded to include 45,119 schools and 6.7 million children.

In 1946, Congress established a permanent National School Lunch Program (NSLP). In the legislation, adequate child nutrition was explicitly recognized as a national security priority. The program was administered by the states, which were required to match federal dollars. Nutritional standards were set by the federal government, and states were required to provide free and reduced priced lunches to children who could not pay.

Childhood Obesity Epidemic

Fast-forward half a century. By 2009, the Department of Defense reported that more recruits were being rejected for obesity than for any other medical reason. This was around the same time that First Lady Michelle Obama was taking on childhood obesity as a national health crisis.

Childhood obesity, reports the Centers for Disease Control, has more than doubled in children (to 18 percent) and quadrupled in adolescents (to 21 percent) in the past 30 years. In 2012, more than 30 percent of American children and adolescents were overweight or obese. These children are at increased risk for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, bone and joint problems, sleep apnea, and social and psychological problems such as stigmatization and poor self-esteem, according to the CDC. By 2030, 50 percent of Americans are predicted to be obese, according to the Harvard School of Public Health.

In the American Indian community, the rate of obesity is even higher. In 2010, the Indian Health Servicereported that 80 percent of American Indian/Alaska Native adults and about 50 percent of AI/AN children were overweight or obese.

Obese and overweight children have access to too many cheap calories with too little nutritional value, leading to the paradox of malnourished overweight children. Poor nutrition, often in the form of too much sugar and other simple carbohydrates, can lead to diabetes, which is rife in AI/AN communities.

Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act

Michelle Obama’s child health initiative included her “Let’s Move!” exercise campaign, the first-ever task force on child obesity and her backing for the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, which passed Congress with bipartisan support in 2010.

The act set new standards, which went into effect in early 2012, for school lunches. These include reduced calories, reduced sugar and reduced sodium combined with increased fresh fruits and vegetables and whole grains. In some cases, schools’ inability to prepare nutritionally adequate, attractive, kid-friendly meals under the new guidelines has led them to drop out of the NSLP altogether. Despite the fact that as of September 2013, only 524 out of 100,000 schools participating in the NSLP, or one half of one percent had dropped out, news coverage has been extensive, complete with photos of unappetizing meals, accounts of student protests and a good deal of criticism of Michelle Obama, who as the point person for the healthy school lunch initiative, is an obvious target.

Poor Children Need School Lunches

But the schools dropping out of the program are mostly schools with few students who qualify for free and reduced-price school lunches. The federal government mandates that schools participating in the NSLP provide free lunches for children from families whose incomes are 130 percent of the poverty level or less. That is, if the poverty level for a family of four is $24,000 per year, then children from families of four whose income is under about $31,200 per year are eligible for free lunches. Reduced-price lunches must be provided for children from families with incomes between 130 percent and 185 percent of the poverty level. So if the poverty level is $24,000 for a family of four, children from families of four earning between $31,200 and $44,400 are eligible for reduced priced lunches. Reduced price lunches may cost no more than $0.40.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 68 percent of AI/AN students are eligible for free and reduced-price school lunches, compared with only 28 percent of white students. USDA dataindicate that 70 percent of children receiving free lunches through the NSLP are children of color, as are 50 percent of students receiving reduced-price lunches.

The very public criticism of the new guidelines poses a threat to AI/AN and other children of color, as well as poor children in general. If the loudest voices cause the federal government to back down on the nutrition standards, the children who will be most affected are those who rely on school breakfasts, lunches, snacks and summer food programs for a significant portion of their nutrition—that is, poor children, the ones receiving free and reduced-price lunches, as do more than two-thirds of AI/AN children in public and non-profit private schools.

Successful School Lunch Programs in Indian Country

Not everyone is having trouble meeting the new guidelines.

Joe Rice (Choctaw), executive director of the Nawayee Center Schoolin Minneapolis, says his school started serving healthier meals to its 55 American Indian high schoolers long before the new guidelines went into effect. “We’re sponsored by the Minnesota Department of Education so we have a licensed food and nutrition service that allows us instead of buying food from the local district to buy through a caterer who serves healthier food in line with our diabetes initiative. The fresh food from our garden and the healthier food from the caterer mean that we’re addressing one of the two modifiable risk factors for diabetes, which is diet. We’re getting away from sugar and saturated fat and more into healthy whole foods.”

And that’s having an impact. The school screens the kids every year and those who have been with the program for a while “typically have better blood glucose levels, and they report exercising and eating more healthy foods throughout the week. We also see healthier BMIs for the kids who have been in the program longer. Overall, we get good health results.”

The garden is a kid-centered endeavor. The students designed and built the garden and decide what crops to grow. The garden, says Rice, is “reconnecting kids to the earth. I remember the first time we had some stuff from the garden, the kids refused to eat it because it came out of the ground.” It also serves as a means of teaching biology, botany, math and language. “We found that gardening could be the starting point for a very rich curriculum and for cultural preservation and revitalization.”

The STAR Schooljust outside Flagstaff, Arizona, serves about 120 Navajo students in grades pre-K through 8. There, too, gardening is a key component of the nutrition program, although until the school can get its gardens and food safety practices certified by the government, garden produce is used only for cooking classes and community events.

Louva Montour (Diné) is food services manager. She says the school has had no trouble meeting the new guidelines. STAR School has its own garden and greenhouses, and students also work on a Navajo farm about 20 miles from the school, where they help with planting, watering, weeding and harvesting. “It really helps that they get hands-on experience working with food, from planting, even preparing the soil, composting (Our kids know a lot about composting!), the whole cycle,” says Montour.

Montour gives an example of the value of having kids grow the food they are going to eat: “We’re on our third year now using our salad bar. When we started putting out different types of vegetables, like beets, the students didn’t really know what beets were and they weren’t really trying it. But then they grew some in our greenhouse. Once they harvested them—those things are really big, about half a pound!—kids were saying ‘What is it?’ and ‘I want to eat it.’ They cleaned it and then we just cut it up right there because they wanted to eat it right there. And we let them because that’s the time for them to try it, when they’re willing.”

Beets have become a salad bar favorite, she says, as have other unlikely vegetables such as kale. Even though the school cannot yet use produce from its own gardens or those of local Navajo farmers, they are able to get local and organic produce through their regular food distributor who works with local producers.

Special Circumstances in Indian Country

Dianne Amiotte-Seidel, Oglala Sioux, project director/marketing coordinator for an ANA grant awarded to the InterTribal Buffalo Councilin South Dakota, which is a coalition of 56 tribes committed to reestablishing buffalo herds on Indian lands in a manner that promotes cultural enhancement, spiritual revitalization, ecological restoration, and economic development.

Amiotte-Seidel has already more than met the grant’s requirement that she introduce bison meat, which is much healthier for kids than beef, into eight school lunch programs, but it hasn’t been easy. “You can’t just put buffalo meat in the schools. You have a lot of different steps to take and each state is different,” she says.

In order for a school to serve bison, “a tribe has to have enough buffalo to supply the school for one meal a week or a month, or whatever, and then they have to have a USDA plant nearby. They have to be willing to sell the buffalo meat to the school for the price of beef and they have to be able to have a supplier from a USDA plant take the meat to the school. The meat needs to bear a child nutrition label. The school has to be able to have a supply area big enough store the bison meat they need for the year, since tribes usually only do their harvest once a year.”

Amiotte-Seidel adds, “The biggest obstacle is the requirement to have USDA-certified slaughtering plants, because on the reservations that I’m dealing with, let’s use Lower Brule, for example. Lower Brule is four or five hours away from a certified USDA plant. They have to haul buffalo four to five hours to have USDA certify the meat for the school.”

This is one area where perhaps guidelines should be modified to better fit the unique circumstances in Indian Country and other areas where they present a burden so severe that the NSLP fails to meet its original goal—feeding poor children—as well as it could.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/12/09/how-national-school-lunch-program-working-indian-country-158189