By Kalvin Valdillez, Tulalip News

“My father was one of the main people to work with the elders to bring the Salmon Ceremony back. A lot of these songs were almost lost,” said Tulalip Chairwoman, Teri Gobin. “It was Harriette Shelton Dover and all these iconic elders that wanted to make sure this was carried on. That was so important. My mom was the one who brought the cakes, and we would visit and write everything down to keep it for future generations. And that’s what’s most important, that these young ones are learning now.”

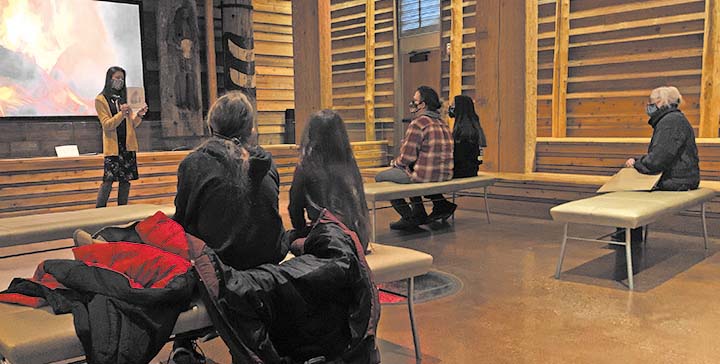

Close to one hundred tribal members met at the Tulalip Gathering Hall on the evening of April 21st for the first Salmon Ceremony practice of the year. Revived nearly 50 years ago, the annual event pays homage not only to the salmon for providing nourishment for the tribal community, but also to all the local fisherman who are preparing for a season out on the Salish Sea.

This year, Salmon Ceremony will be held on Saturday June 11th beginning at 10:30 a.m. at the Tulalip Longhouse. At the height of the pandemic, the Salmon Ceremony was canceled for the very first time since it’s revival in 2020 to limit the spread of the infectious disease. And although the people were excited to see the cultural event return in 2021, many lifetime Salmon Ceremony participants still felt as though something was missing.

Every year, with the exception of the past two, tribal members engage in a cultural immersion experience, weeks ahead of Salmon Ceremony, when the community begins preparations for the event. During Salmon Ceremony practice, tribal members get an opportunity to get reacquainted with the songs, dances and stories of the annual event, so when the day comes to pay respect to the first catch of the season, everything is executed precisely in honor of the salmon.

Each week, a walkthrough of Salmon Ceremony takes place at the practice sessions, allowing the chance for the people to learn the significance behind every song and dance that is performed and offered at the ceremony. This is also the perfect time for newcomers to learn about the proceedings that take place inside the longhouse and alongside the bay when the first king salmon of the year returns to local waters.

Although the turnout for the first practice was great, Teri stated that there is still plenty of room at the large Gathering Hall for more people to attend the practices, and invited the community to come out and take part in preparations of the ceremony. Salmon Ceremony practices are held every Thursday at 5:00 p.m., where a meal and good company is promised to each participant. All of the practice sessions will take place at the Gathering Hall except for the last practice on June 9th, which will be held at the longhouse.

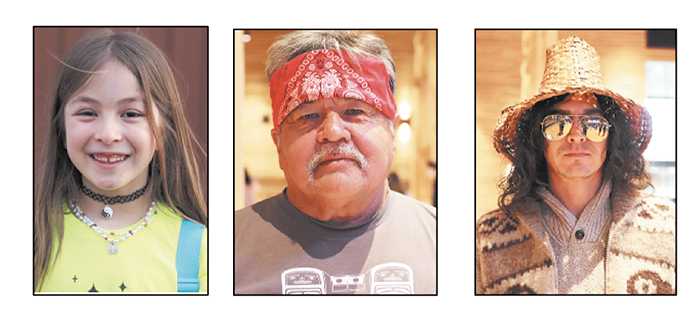

As practices continue, Tulalip News will feature a weekly mini-series, leading up to Salmon Ceremony, focused on the traditions and hard work that goes into the cultural event each year. This week, we asked a handful of participants what the Salmon Ceremony means to them personally and received a number of great responses from youth to elders.

Said Tulalip tribal member, Andrew Gobin, “It’s about taking time out to recognize the old teachings and carrying them forward. That’s what the practices are about. We talk about the old teachings here and how you conduct yourself in ceremonial spaces, what’s expected of you. The practices are just as important as the day.”

Salmon Ceremony participants

Kamiakin Craig: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony?

Since I was a baby. Probably around 18-19 years.

Why is it important to you? It was very important to my grandfather who passed away, Kai Kai. I share his Indian name and I really try to hold up what he was trying to do here with Salmon Ceremony. He loved this and I can remember having fun with him here too, so it’s important to me.

Andrew Gobin: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? 32 years.

Why is it important to you? It’s important for a lot of reasons – just the basic teachings about respecting the salmon, remembering to take care of the salmon and respect those things in nature that sustain our culture and lives. I take Salmon Ceremony very seriously when it comes to the blessing and the spiritual side of it. It’s something that was instilled in me my whole life. I feel like it’s my responsibility to carry and pass down as it’s been given to me.

Arielle Valencia : How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? About a year and a half.

Why is it important to you? I find it important because this was taken away from us and it’s good that we’re reclaiming it and getting back together. Especially since COVID, it kind of struck natives a little harder from our traditional teachings. I feel like this is a good chance to get it all back.

Lizzie Mae Williams: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? Since I was a baby.

Why is it important to you? It’s fun and part of my culture, and I get to hang out with family.

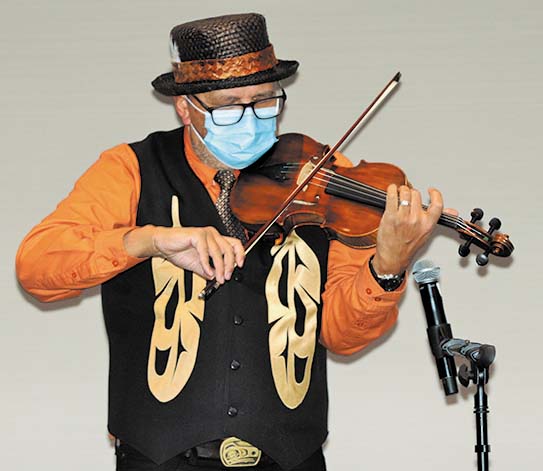

Bill ‘Squall-See-Wish’ Gobin: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? I’ve been participating since about 1982.

Why is it important to you? Because I am a fisherman and honoring the first salmon that comes back to the bay is very important for cultural reasons. Being a fisherman, I’m the one who wants to catch

that first fish.

C.J. Jones: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? Since I was two.

Why is it important to you? Our fish are our people, that’s who we come from. We’re the salmon people of the killer whale clan. Without the killer whales, we wouldn’t be alive, and the salmon helped us survive

for generations.

Jackson Gobin: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? Since I was like one or two.

Why is it important to you? I get to sing songs and it’s really fun.

Foster Jones: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony?

Since I was seven.

Why is it important to you? Because I can learn new things about our culture.

Teri Gobin: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony?

Since day one. I was here at the first one when we restarted it back with my father. I was actually here before that when we were sitting around the tables with the elders learning the songs and bringing

it all back.

Why is it important to you? We’ve come a long way and we’ve been practicing for a lot of years. What is most important now is that we are making sure the young ones are learning the songs, the dances and about those elders who brought it back again.

Kali Joseph: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony?

Actually not very many years, for like four or five years now.

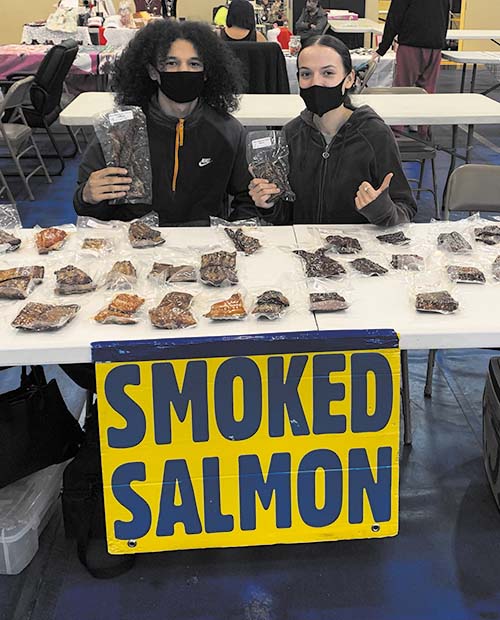

Why is it important to you? First of all, it’s so cool being able to gather after all these years of being in isolation and through COVID. It’s important because, like one of the speakers said tonight, salmon is a big part of our way of life. It’s a great way to continue to pass down the teachings and share the meaning of Salmon Ceremony to the youth so it can be around for the next seven generations.

David Bohme: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? I haven’t been in years. This is the first time that I’ve come in a long time.

Why is it important to you? The culture. I’ve been kind of disconnected for a while and the kids are getting older and I want to teach them about the culture, our identity. I brought my daughters down here because I want to get them into it. And I want to get back it into myself, and just keep participating.

Marie Myers: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? It’s been three or four years now.

Why is it important to you? I started participating and getting more involved in my culture since I lost my mom because it helps me feel connected to her. It makes me feel good participating – singing and dancing. I think it’s amazing when the little kids come to the practices, it’s fun to teach them to sing and dance.

Troyleen Johnson: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? Since I was 13.

Why is it important to you? It’s important for me to teach her (Neveah) and my other nieces and nephews about our culture.

Neveah (left): How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? This is my first year!

Why is it important to you? I haven’t been to Salmon Ceremony yet, but I am excited to learn!

Image Enick: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? Salmon Ceremony was introduced to me when I was a little boy at Quil Ceda Elementary. Me and my friend were introduced to it when we were pretty young. Ever since then, I’ve always tried to peep my head in every now and then, and try to attend the Salmon Ceremony when I can. And if I’m not able to, I try to be at the practices.

Why is it important to you? To understand and learn the songs that have been brought back by the elders, the main songs of the ceremony. It’s also important because I’ve always thought of it as a good way for the young ones to learn the songs and what it is to see and show respect, and to actually see the young ones go out there and dance.

Weston Gobin: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony?

Eleven years, since I was two – really since I was born, but I’ve participated as soon as I was able to.

Why is it important to you? Because it’s giving me all the teachings I need and it’s coming from my aunties and uncles. My family is all around me and I am learning all of my teachings.

Josh Fryberg: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony?

The first time I came to Salmon Ceremony I was probably about nine years old, but the time when I start bringing my family was 2018.

Why is it important to you? The reason it’s important to me is because it’s a part of our culture and we want to preserve it for our future generations while honoring our past generations who kept it alive for each and every one of us.

Shoshanna Haskett: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? Four years, I used to go when I was little and we’re now getting back into it.

Why is it important to you? It is important for me to be able to teach my kids our culture, our history and I love watching the warriors go out and do their dance.

Shane McLean: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? Ten years!

Why is it important to you? To pay respects to the salmon that continue to feed us and give us life. To show them respect and honor them the best way we can.

Ronald Cleveland: How long have you participated in Salmon Ceremony? A couple years now.

Why is it important to you? It’s important for me to pay respect to our elders and the salmon, and I like drumming.