By Alysa Landry

Navajo Times

WASHINGTON, May 30, 2013

T he marketing of Navajo arts and crafts has a complex history with deep ties to economics and tribal identity, but one thing remains simple: the Navajo name belongs to the people.

That’s according to Brian Lewis, an attorney with the Navajo Department of Justice who has headed the tribe’s case against Urban Outfitters since the company began marketing Navajo-themed clothing and accessories in 2011.

The Nation “has the exclusive right to use its Navajo name and trademarks on products that are marketed and retailed as being authentically Navajo,” Lewis said. “People who buy products with the name and trademark ‘Navajo’ expect that those products will have valid association with the Navajo Nation and Navajo people.”

The case, which last week was placed on hold as the parties work toward a settlement, is expected to set precedent as the Nation seeks to curb the theft of intellectual property and emerge as the sole and rightful owner of its name.

Although the case appears novel, it is not, Lewis said.

The Indian Arts and Crafts Act, passed in 1990, came as a response to individuals and corporations that misrepresented products as Indian-made. The law prohibits any marketing or sale of items in a manner that falsely suggests they are made by American Indians.

“Corporate theft of property from Indians … is old school,” Lewis said. “It was non-Indian corporations’ profiting from posing their products as having been made by Native Americans that led to the enactment of the (law) in the first place.”

The point of the law, and of the Navajo Nation’s lawsuit against Urban Outfitters, is to maintain credibility with consumers, he said.

The tribe is seeking monetary damages from the company of up to seven or eight figures, Lewis said. It also “looks to stop this kind of deceptive behavior to keep the integrity of its property and protect consumers from getting tricked.”

“The first appropriate outcome if for Urban Outfitters to stop making money off the unlawful use of the Navajo Nation’s intellectual property,” Lewis said. “The second appropriate outcome here is for Urban Outfitters to compensate the Navajo Nation for the profits the company made.”

In short, the tribe wants consumers to rest assured that when they buy products labeled “Navajo,” they are, indeed, manufactured by members of the tribe.

Ownership of the Navajo name – and of the arts and crafts associated with it – is complicated, however.

According to author Erika Marie Bsumek, who researched Navajo culture in the marketplace from the return from Fort Sumner until the 1940s, many of the traditional crafts became symbols of a romanticized and primitive culture.

The Navajo historically worked in silver and wool, creating items for household uses or adornment, Bsumek wrote. Yet with the arrival of Anglo settlers – and their discovery of the Navajo crafts – the industry shifted into a complex framework where arts and crafts became part of a broader economic landscape.

This resulted in complicated links between the tourism industry and Navajo identity, which often was portrayed as primitive and vanishing despite the tribe’s growing numbers, Bsumek wrote. The tourism industry and anthropologists constructed a Navajo identity “with little or no input from Navajos themselves.”

“For a good majority of consumers, goods made by Indians were infused with symbolic, material and cultural capital,” she wrote. “Navajo blankets and jewelry were prestigious in that they conveyed a set of racialized beliefs, represented a financial investment and transmitted a series of meanings about modernity and civilization to the whites who purchased them.”

With such a history, it is no surprise that the tribe guards its name and strives to protect it from companies that might further dilute its identity, said Richard Stim, a San Francisco-based trademark attorney who is watching the Nation’s case against Urban Outfitters. The Navajo Nation has proven to be a leader among tribes in protecting its name, he said.

“The whole point of trademark law is to not confuse the consumer,” he said. “The Navajo Nation has been very active. It has taken the initiative to protect its name.”

In its lawsuit, the Nation claims the Pennsylvania-based Urban Outfitters violated trademark laws and marketed items that were disrespectful to the Navajo culture, including underwear and a liquor flask. Urban Outfitters is an international retail company that markets and retails its merchandise in more than 200 stores and online. Its brands include Anthropologie and Free People.

The company claims American Indian-inspired prints have shown up in the fashion industry for years and that it’s common for designers to borrow from other cultures. The company claims the term “Navajo” is generic and it is seeking a declaration of non-infringement and cancellation of the tribe’s federal trademark registrations.

“The term ‘navajo’ is a common, generic term widely used in the industry and by customers to describe a design/style or feature of clothing and clothing accessories, and therefore, is incapable of trademark protection,” the company said in court documents. It argues that the Nation has not taken action during the years third parties used the term, therefore abandoning its rights to the name.

The company also asserts that it sells “hip clothing and merchandise” to “culturally sophisticated young adults” and in no way competes with Navajo arts and crafts, which generally are not sold in “specialty retail centers, upscale street locations and enclosed malls.”

“Nothing in the title of the store, the layouts of the stores or the manner in which any of the goods are marketed or sold suggests in any way that Urban Outfitters is marketing or selling products supplied by the Navajo Nation,” the company said in court documents. It argues that many other upscale clothing retailers also are marketing American Indian-themed merchandise.

The tribe holds at least 10 trademarks on its name, covering clothing, footwear, household products, textiles and online retail sales. It has used the name “Navajo” since 1894 and has 86 trademarks registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Urban Outfitters, however, contends that the Nation does not hold those trademarks.

The two sides have wrangled over rights to the name since 2012 when the Nation filed a lawsuit against Urban Outfitters, which was marketing more than 20 products, including jackets, earrings, scarves and sneakers, as “Navajo” or “Navaho.”

In January, the court denied Urban Outfitters’ motion to have the case transferred from New Mexico to Pennsylvania. Last week, a U.S. District Court judge in Albuquerque threw out all deadlines for discovery and responses in the case. The two sides have until July 29 to agree on a mediator for settlement discussions.

The case has gained notoriety not only because of the absurdity of the Navajo-themed underwear, which has sparked outrage and controversy from other tribes and activists, but also because it raises questions about who can profit from a name.

“This case is about a multi-billion-dollar corporation having profited from misrepresentations that its products were associated with the Navajo Nation and American Indians,” Lewis said. “Meanwhile, the Navajo Nation and American Indians lost out from consumers’ having being duped.”

The stakes are higher in a trademark case when the name describes a community or ethnic group, Lewis said.

Some consumers “have an affinity with the Navajo Nation and its people and they purchase Navajo products, which they know are associated with the unique and distinctive institution and its members,” he said. “This expectation of a connection is undermined when a company puts the same Navajo name and trademark on its products … in competition with the products that are authentically connected to the Navajo Nation.”

Stim hopes the case sets precedent and forces big retailers to think twice before they use the names of ethnic groups in marketing.

“It’s like Walt Disney saying ‘Don’t mess with Snow White,'” he said. “I hope this sets a big precedent. I hope it sends the message to other clothing retailers so they don’t go near this.”

Russian-born Canadian filmmaker Anita Doron directed the film, with young newcomer Joel Evans starring as the teen outsider protagonist. He becomes involved in an unlikely triangle when he becomes smitten with the prettiest girl at school and also befriends a cool new student.

Russian-born Canadian filmmaker Anita Doron directed the film, with young newcomer Joel Evans starring as the teen outsider protagonist. He becomes involved in an unlikely triangle when he becomes smitten with the prettiest girl at school and also befriends a cool new student.

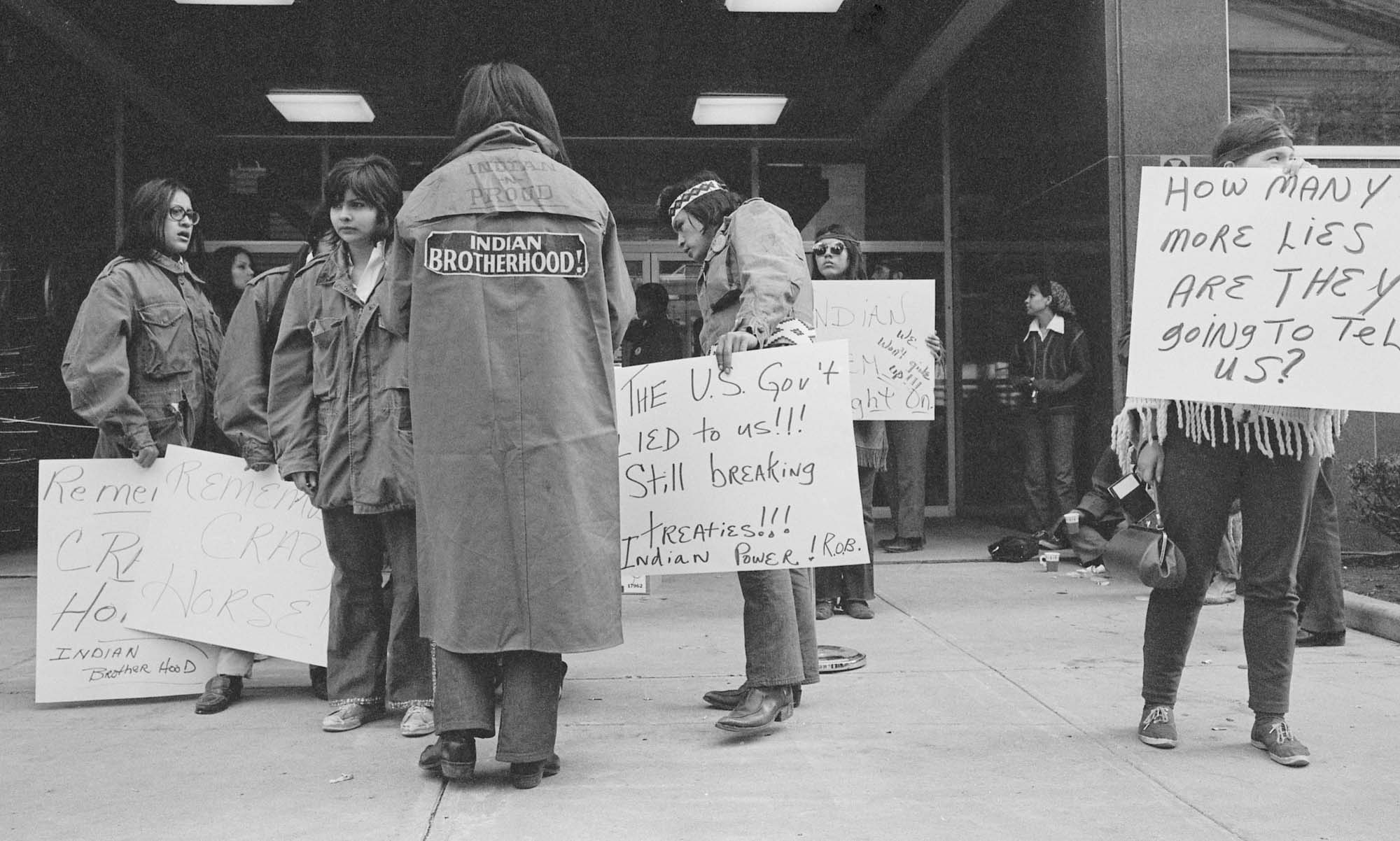

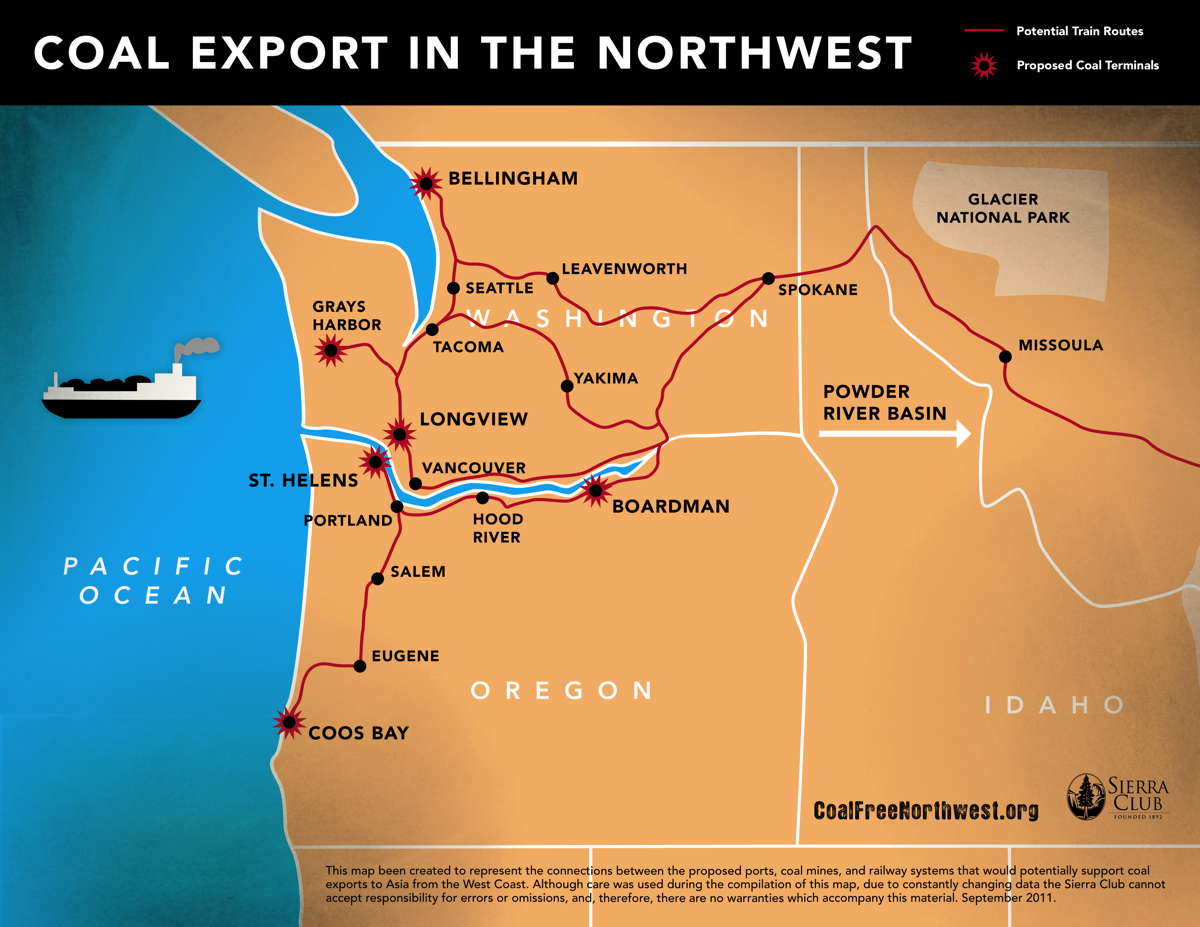

An excerpt from the complaint, still being refined into its final, legal form, reads: “This letter serves notice as complaint, that the crime of genocide is being committed, in an ongoing manner, against the matriarchal Tetuwan Lakota Oyate of the Oceti Sakowin, an Indigenous First Nation people whose ancestral lands comprise a large area of the Northern Great Plains of Turtle Island, the continent known as North America.” As evidence, the Lakota cite systematic American usurpation of their land and sovereignty rights, imposition of third world living conditions on the majority of Lakota, US assimilation policies that threaten the future of their language, culture and identity, and environmental depredations including abandoned open uranium mines and the proposed Keystone XL Pipeline slated to invade the Pine Ridge Reservation. The Lakota grandmothers and their allies in the Lakota Solidarity Project have even produced a powerful, full-length documentary, Red Cry, available on DVD or online at

An excerpt from the complaint, still being refined into its final, legal form, reads: “This letter serves notice as complaint, that the crime of genocide is being committed, in an ongoing manner, against the matriarchal Tetuwan Lakota Oyate of the Oceti Sakowin, an Indigenous First Nation people whose ancestral lands comprise a large area of the Northern Great Plains of Turtle Island, the continent known as North America.” As evidence, the Lakota cite systematic American usurpation of their land and sovereignty rights, imposition of third world living conditions on the majority of Lakota, US assimilation policies that threaten the future of their language, culture and identity, and environmental depredations including abandoned open uranium mines and the proposed Keystone XL Pipeline slated to invade the Pine Ridge Reservation. The Lakota grandmothers and their allies in the Lakota Solidarity Project have even produced a powerful, full-length documentary, Red Cry, available on DVD or online at

Published: May 30, 2013

Published: May 30, 2013