Idle No More and Building Bridges Through Native Sovereignty

By Zoltan Grossman as seen on Unsettling America

“The natural resources we all depend upon must be protected for future generations….to bring us to a place where there is a quality of life, and where Indians and non-Indians are to understand one another and work together.” — Billy Frank, Jr. (Nisqually)

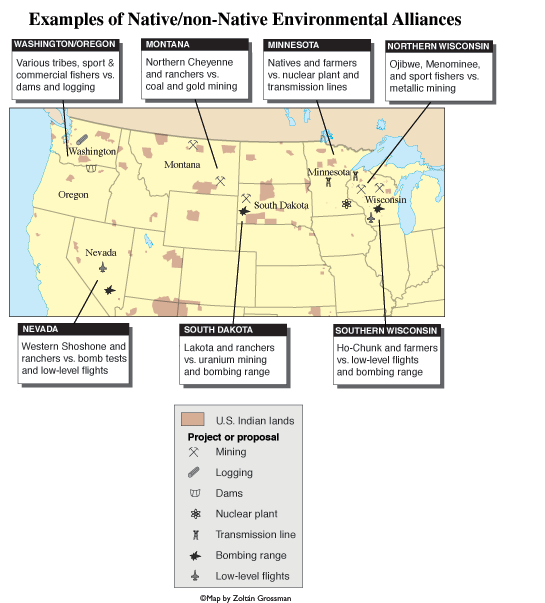

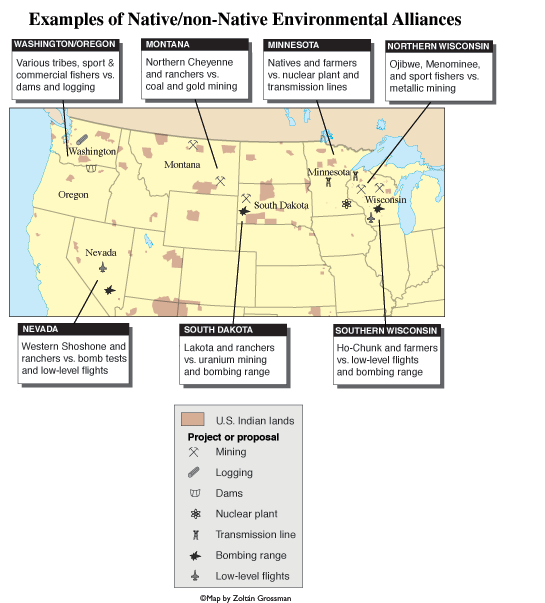

In the 2010s, new “unlikely alliances” of Native peoples and their rural white neighbors are standing strong against fossil fuel and mining projects. In the Great Plains, grassroots coalitions of Native peoples and white ranchers and farmers (including the aptly named “Cowboy and Indian Alliance”) are blocking the Keystone XL oil pipeline and coal mining. In the Pacific Northwest, Native nations are using their treaties against plans for coal and oil terminals, partly because shipping and burning fossil fuels threatens their treaty fishery. In the Great Lakes, Bad River Ojibwe are leading the fight to stop metallic mining, drawing on past anti-mining alliances of Ojibwe and white fishers. In the Maritimes, Mi’kmaq and Maliseet are confronting shale gas fracking, joined by non-Native neighbors.

The Idle No More movement similarly connects First Nations’ sovereignty to the protection of the Earth for all people—Native and non-Native alike. Idle No More co-founder Sylvia McAdam states, “Indigenous sovereignty is all about protecting the land, the water, the animals, and all the environment we share.” Gyasi Ross observes that Idle No More “is about protecting the Earth for all people from the carnivorous and capitalistic spirit that wants to exploit and extract every last bit of resources from the land…. It’s not a Native thing or a white thing, it’s an Indigenous worldview thing. It’s a ‘protect the Earth’ thing.”

A debate around Idle No More discusses how the movement can reach the non-Native public. In any alliance, the same question always arises at the intersection of unity and autonomy. Should the so-called “minority” partners in the alliance set aside their own distinct issues in order to build bridges to the “majority” over common-ground concerns, such as protecting the Earth? Should Native leadership, for example, not as strongly assert treaty rights and tribal sovereignty to avoid alienating potential allies among their white neighbors? Conventional wisdom says that we should all “get along” for the greater good, and that different peoples should only talk about “universalist” similarities that unite them, not “particularist” differences that separate them.

In my both my activism and academic studies, I’ve often wrestled with this question, and spoken with many Native and non-Native activists and scholars who also deal with it. Based on their stories and experiences, I’ve concluded that the conventional wisdom is largely bullshit. Emphasizing unity over diversity can actually be harmful to building deep, lasting alliances between Native and non-Native communities. History shows the opposite to be true: the stronger that Native peoples assert their nationhood, the stronger their alliances with non-Indian neighbors.

Unlikely Alliances

Since the 1970s, unlikely alliances have joined Native communities with their rural white neighbors (some of whom had been their worst enemies) to protect their common lands and waters. These unique convergences have confronted mines, dams, logging, power lines, nuclear waste, military projects, and other threats. My main education has been as an activist in unlikely alliances in South Dakota and Wisconsin. As a geography grad student I later studied them in other states (such as Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington) where they took different paths from treaty conflict to environmental cooperation, and had varying degrees of success.

* In South Dakota in the late 1970s, Lakota communities and white ranchers were often at odds over water rights and the tribal claim to the sacred Black Hills. Yet despite the intense Indian-white conflicts, the two groups came together against coal and uranium mining, which would endanger the groundwater. The Native activists and conservative-looking ranchers formed the Black Hills Alliance (where I began my activism 35 years ago) to halt the mining plans, and later formed the Cowboy and Indian Alliance (or CIA), which has since worked to stop a bombing range, coal trains, and oil pipeline.

* In roughly the same era of the 1960s and ‘70s, a fishing rights conflict had torn apart Washington State. The federal courts recognized treaty rights in 1974, and by the 1980s the tribes began to use treaties as a legal tool to protect and restore fish habitat. The result was State-Tribal “co-management,” recognizing that the tribes have a seat at the table on natural resource issues outside the reservations. The Nisqually Tribe, for instance, is today recognized in its watershed as the lead entity in creating salmon habitat management plans for private farm owners, and state and federal agencies. The watershed is healing because the Tribe is beginning to decolonize its historic lands.

* Another treaty confrontation erupted in northern Wisconsin in the late 1980s, when crowds of white sportsmen gathered to protest Ojibwe treaty rights to spear fish. Even as the racist harassment and violence raged, tribes presented their sovereignty as a legal obstacles to mining plans, and formed alliances such as the Midwest Treaty Network. Instead of continuing to argue over the fish, some white fishing groups began to cooperate with tribes to protect the fish, and won victories against the world’s largest mining companies. After witnessing the fishing war, seeing the 2003 defeat of the Crandon mine gave us some real hope.

In each of these cases, Native peoples and their rural white neighbors found common cause to defend their mutual place, and unexpectedly came together to protect their environment and economy from an outside threat, and a common enemy. They knew that if they continued to fight over resources, there may not be any left to fight over. Some rural whites began to see Native treaties and sovereignty as better protectors of common ground than their own governments. Racial prejudice is still alive and well in these regions, but the organized racist groups are weaker because they have lost many of their followers to these alliances.

Cooperation growing from conflict

It would make logical sense that the greatest cooperation would develop in the areas with the least prior conflict. Yet a recurring irony is that cooperation more easily developed in areas where tribes had most strongly asserted their rights, and the white backlash had been the most intense. Treaty claims in the short run caused conflict, but in the long run educated whites about tribal cultures and legal powers, and strengthened the commitment of both communities to value the resources. A common “sense of place” extended beyond the immediate threat, and redefined their idea of “home” to include their neighbors. As Mole Lake Ojibwe elder Frances Van Zile said, “This is my home; when it’s your home you try to take as good care of it as how can, including all the people in it.”

These alliances challenge the idea that “particularism” (such as Native identity) is always in contradiction to “universalism” (such as environmental protection). The assertion of Indigenous political strength does *not* weaken the idea of joining with non-Natives to defend the land, and can even strengthen it. The stories of these alliances may identify ways to weave together the assertion of differences between cultures with the goal of finding common-ground similarities between them. (I’m perhaps drawn to this hope because of my own Hungarian background, with a Jewish father whose family was decimated by genocide, and a Catholic mother whose family valued its cultural identity, and my attempts to navigate between the fear and celebration of ethnic pride.)

Alliances based on “universalist” similarities tend to fail without respecting “particularist” differences. The idea of “why can’t we all just get along” (like “United We Stand”) is often used to suppress marginalized voices, asking them to sideline their demands. This overemphasis on unity makes alliances more vulnerable, since authorities may try to divide them by meeting the demands of the (relatively advantaged) white members. A few alliances (such as against low-level military flights) floundered because the white “allies” declared victory and went home, and did not keep up the fight to also win the demands of their Native neighbors. “Unity” is not enough when it is a unity of unequal partners; Native leadership needs to always be involved in the decision-making process.

But successful alliances can go beyond temporary “alliances of convenience” to building lasting connections. In Washington State, local tribal/non-tribal cooperation to restore salmon habitat provides a template for collaboration in response to climate change. The Tulalip Tribes, for example, are cooperating with dairy farmers to keep cattle waste out of the Snohomish watershed’s salmon streams, by converting it into biogas energy. Farmers who had battled tribes now benefit from tribal sustainable practices. The anthology we recently edited at The Evergreen State College, “Asserting Native Resilience”, tells some of these stories of local and regional collaboration for resilience.

Idle No More and “Occupy”

Idle No More and “Occupy”

With the rise of the Idle No More and Occupy movements, we have an unprecedented opportunity to grow this cooperation beyond local and regional levels, to national and global scales. Whether Occupy or Idle No More still draw huge crowds is beside the point, because they both have popularized powerful ideas that were not widely discussed even three years ago. The Occupy movement (despite its unfortunately inappropriate name) questions the concentration of wealth under capitalism, the economic system that has also occupied and exploited Native nations. Although a few protest camps (like in Albuquerque), changed their name to “(un)Occupy” to make this point, other camps rarely extended the discussion beyond class inequalities.

Idle No More deals with the flip side of the coin: how to make an understanding of colonization relevant to the majority struggling to live day-to-day under capitalism. Leanne Simpson* *sees Idle No More as “an opportunity for the environmental movement, for social-justice groups, and for mainstream Canadians to stand with us…. We have a lot of ideas about how to live gently within our territory in a way where we have separate jurisdictions and separate nations but over a shared territory. I think there’s a responsibility on the part of mainstream community and society to figure out a way of living more sustainably and extracting themselves from extractivist thinking.”

While the Occupy movement has questioned the unequal distribution of wealth in Western capitalism, Idle No More confronts the colonization of land and extraction of the resources that are the basis of that wealth. While thinking about fairly distributing the stuff, think about where the stuff comes from in the first place—as the spoils of empire. Idle No More’s seemingly “particularist” message actually advances the universalist goals of the global anti-capitalist movement. Our solutions should not aim for a more egalitarian society that continues to exploit the Earth, nor a more sustainable society that continues to exploit human beings—the world needs both social equality and ecological resilience. And both movements have common historical roots, because the class system and large-scale natural resources extraction both originated in Europe at roughly the same time.

Colonizing Europe

To witness the decolonization of Native lands is to see a small reversal in the process of European colonization that began centuries ago, within Europe itself. In her classic study *The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution*, Carolyn Merchant documents how Western European elites suppressed the remnants of European indigenous knowledge, as a key element of colonizing villagers’ lands and resources in the 17thcentury. Merchant saw links between the mass executions of women healers (who used ancient herbal knowledge), the draining of wetlands, metallic mining, the restriction of villagers’ hunting, fishing, and gathering rights on lands they had held in common, and the division of the Commons into private plots.

This “enclosure of the Commons” sparked peasant rebellions and Robin Hood-style rebel movements. The Irish resisted English settler colonization, which was a testing ground for methods of control later used in Native America, against clan structures, collective lands, knowledge systems, and spiritual beliefs. In the meantime, the European encounter with more egalitarian Indigenous societies convinced some scholars (such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Lewis Henry Morgan) that class hierarchy was not the natural order, and they in turn influenced many of the social philosophers and rebels of the 19th century.

The elites’ promise of settling stolen Native land became a “safety valve” to defuse working-class unrest in Europe and the East Coast. But even at the height of the Indian Wars, a small minority of settlers sympathized with Native resistance, or opposed the forced removal of their Indigenous neighbors. Some Europeans and Africans attracted to freer Native societies even became kin to Native families. We never read these stories of Native/non-Native cooperation in history books, because they undercut the myth of colonization as an inevitable “Manifest Destiny.” But there were always better paths not followed.

Non-Native Responsibilities

The continued existence of Native nationhood today, as Audra Simpson points out, undermines the claims of settler colonial states to the land. Unlikely alliances can help chip away at the legitimacy of colonial structures, even among the settlers themselves. To stand in solidarity with Indigenous nations is not just to “support Native rights,” but to strike at the very underpinnings of the Western social order, and begin to free Native and non-Native peoples. As Harsha Walia writes, “I have been encouraged to think of human interconnectedness and kinship in building alliances with Indigenous communities… striving toward decolonization and walking together toward transformation requires us to challenge a dehumanizing social organization that perpetuates our isolation from each other and normalizes a lack of responsibility to one another and the Earth.”

By asserting their treaty rights and sovereignty, Indigenous nations are benefiting not only themselves, but also their treaty partners. Since Europeans in North America are more separated in time and place from their indigenous origins, they need to respectfully ally with Native nations to help find their own path to what it means to be a human being living on the Earth–without appropriating Native cultures. It is not the role of non-Natives to dissect Native cultures, but to study Native/non-Native relations, and white attitudes and policies. The responsibility of non-Natives is to help remove the barriers and obstacles to Native sovereignty in their own governments and communities.

Non-Native neighbors can begin to look to Native nations for models to make their own communities more socially just, more ecologically resilient, and more hopeful. As Red Cliff Ojibwe organizer Walt Bresette once told Wisconsin non-Natives fighting a proposed mine, “You can all love this land as much as we do.”

———

Zoltan Grossman is a Professor of Geography and Native Studies at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. He is a longtime community organizer, and was a co-founder of the Midwest Treaty Network in Wisconsin. His dissertation explored “Unlikely Alliances: Treaty Conflicts and Environmental Cooperation Between Rural Native and White Communities (University of Wisconsin Department of Geography, 2002). He is co-editor (with Alan Parker) of “Asserting Native Resilience: Pacific Rim Indigenous Nations Face the Climate Crisis” (Oregon State University Press, 2012).