By Gyasi Ross, Indian Country Today Media Network

POP QUIZ: Think of a list of 5 people whom you do not like or who irritate you. Ethnically, are most of those people on that list 1) Native American, 2) White, 3) Black, 4) Hispanic or 5) Asian?

ANSWER: Most the people on your list are Native, huh?

It’s not your fault—we’re conditioned. See, let me explain. But first, let me clarify a few things.

“Tribe” is a new, anthropological word to describe groups of Native people. It’s not Indigenous to most of our languages; neither is “Nation.” Those words and concepts are not ours. Typically, because Native groups were smaller villages—small settlements—the literal translation of the group name was “band” or camp.”

Still, despite the historical inaccuracies, both ideas have some value to Native people. Both terms imply a group of people, in a discreet area, who have common interests and take care of each other. It implies an extended family that historically stayed together for survival reasons. Those extended families created hunting societies and medicine societies and warrior societies—basically agencies of the Tribe in modern day white-speak—that had no choice but to work together for the survival of the group.

We were hunter/gatherers; if we did not work together for even one season, the group would likely die. Serious consequences.

Observing many modern-day Tribal organizations, I think this quick history lesson begs a question: What happens when the people of a particular Tribe or Nation cease to live in a discreet area (a topic for another day), or more importantly, stop having common interests and taking care of each other? What do you call a group of Native people who no longer associate with each other and whose only common interest is in the success of the gaming enterprise or other economic development interest? Is that still a “Tribe” or “Nation?”

When groups of Native people—legally bound together as tribes, but with no other meaningful connection—ostensibly hate each other, do they really deserve to be called a “tribe” or “nation?”

Maybe. But maybe not. Still, at least in theory tribes and nations are supposed to be about the collective good.

In recent times, there have been very public stories about factions of a particular tribe essentially going to war with other factions within that same tribe. I’ve anecdotally noticed that the vitriol in tribal campaigns has gotten more personal and nastier progressively every campaign season—yet, those same politicians play nice when in front of non-Native cameras or non-Native elected officials. We’re all profoundly aware of real or imagined examples of retaliation and retribution within tribal organizations that carries on inter-family feuds that go back generations. As discussed last week, we see examples of amazing Native projects—like the Shoni Schimmel documentary—that do not happen because of lack of support from Native organizations until after they hit it big. Yet, those same Native organizations will pay for washed-up athletes and politicians who are not even supportive of the Tribe. Also recently, we see examples of Tribes deciding that tribal members are no longer qualified to be tribal members and thus essentially fire them from being tribal members.

With friends (and family) like these, who needs enemies…?

How, exactly, are we supposed to teach our observant Native children to love Native people (and therefore love themselves) when they constantly see Native people attacking Native people (and broadcasting those attacks in newspapers and websites)? How are those same beautiful Native children supposed to learn to carry on a sense of community when people within our communities seem much more likely to treasure outsiders’ opinions than those from within our own communities? Why does it seem so much easier to tear down, destroy and dislike someone who looks like us than someone who is of a different ethnicity?

They see their leaders constantly putting blankets around white peoples’ shoulders and honoring them when they visit our homelands yet, after those white people leave, blasting the Native people who live here every day. No wonder Native people commit violence against other Native people in disgustingly high numbers—we teach our children, from a young age, to love every other race except our own. No wonder Native women are victims of domestic violence—very often from Native men—at a disgustingly disproportionate rate. No wonder our youth commit suicide at grossly disproportionate rates—they learn the following lessons everyday: 1) “It’s ok to hurt Native people.” 2) “Native people are not as valuable as non-Natives.”

Confusing.

We’ve gotta change that. We gotta work on that conditioning, learn AND teach to love Native people unabashedly.

FYI, loving Native people does not mean that we agree with other Native people all the time. Nor does it mean that we pretend to agree with other Native people all the time. We should disagree with each other—debate is good. But loving Native people does mean that we treat our people, Native (and also non-Native, but especially Native) with a level of respect that indicates that “I love you because you are me, and we need to survive together.” That is, if we take Native tribalism and/or nationhood seriously, we will treat our people like, well, our people. If not, we’re not just playing Indian for personal gain and are not truly committed to tribalism and/or nationhood. It’s about the collective good, not the individual—that’s what tribes are.

Loving Native people better simply means that we don’t look for reasons to tear other Native people down. Tear someone else down—go after Karl Rove or JR Ewing or Bane or someone truly bad, not just some Native schmuck that you don’t agree with.

We need to love our own people better. We can disagree with each other without assassinating each other’s characters. If we don’t learn this soon, our beautiful children will replicate the dysfunctional ways that they observe and our own people will (continue to be) our worst enemies.

Gyasi Ross

Blackfeet Nation Enrolled/Suquamish Nation Immersed

Activist/Attorney/Author

Twitter: @BigIndianGyasi

www.cutbankcreekpress.com

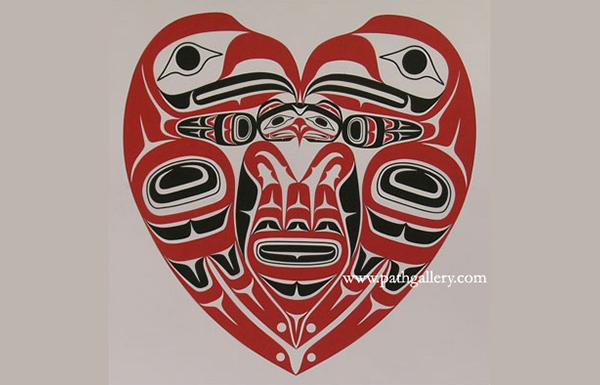

“Eagle’s Heart,” seen at the top of this page, is a print by Wayne Edenshaw, Haida. To purchase or see more of Edenshaw’s work, visit pathgallery.com.

Read more at http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2013/04/15/loving-native-people-better-vol-1-pop-quizzes-and-friends-and-family-these-148817