By Liz Brazile, Crosscut; photos by Micheal Rios

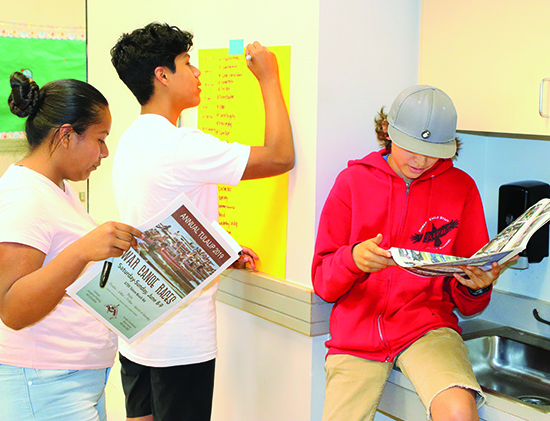

About a dozen Seattle-area youth gathered at Bitter Lake Community Center on a recent Saturday afternoon for a day of studying the journalistic process. The students, ages 12 to 18, have spent part of their summer break learning what it means to produce news in a digital era, during a time of significant change in how people consume media.

During the session, they learn about the intersections of mainstream and tribal news media.

“How does this look different from a regular newspaper like The Seattle Times?” asks journalist Micheal Rios, holding up a recently published issue of the Tulalip Syeceb newspaper. The students take notice of the front page’s text, which isn’t in English.

“So this is Lushootseed, the traditional language of Tulalips,” Rios says. “Some would say its Northern Lushootseed,” he continues, heard in “the Coast Salish area that runs from about Nisqually to Vancouver, B.C. It’s a shared language.”

Now serving its second cohort, this multiday teen journalism workshop is hosted by the Urban Native Education Alliance as an extension of its Clear Sky Native Youth Council program. Participating students represent a number of tribes, including the Muckleshoot, Lakota, Arapaho and Yakama.

The two-week series is aimed at increasing news media literacy and imparting journalistic skills to a rising generation of Native American storytellers.

Washington’s Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction convened a task force in 2016 to advise school districts on how to integrate media literacy and digital citizenship teachings into curricula. Several Puget Sound schools, including those in Seattle, Kent, Auburn and Edmonds, have implemented such lessons to varying degrees.

But mentors with Clear Sky are hoping to take this kind of education a step further. Their goal, in part, is to prepare students to amplify underrepresented Native voices and communities.

“We’re hoping they walk away with better reading and writing skills … as well as some knowledge on how you can use media to help your community,” says A.J. Oguara, Clear Sky program coordinator and former student. “Even if [an activity] helps them interpret an existing idea that they’re already kind of familiar with, to understand it better, it’s pretty valuable.”

Beginning in 2016, a group of researchers and advocates with the Reclaiming Native Truth Project at the First Nations Development Institute set out to uncover the impact of negative portrayals of Indigenous people in the media.

Among the team’s findings were that the voices of present-day Native peoples are overwhelmingly missing in school curricula, news media, pop culture entertainment and the legal system. That absence, according to a 2018 report, has contributed to a general lack of understanding of and attention given to Native issues, as well as misconceptions about the Native population shrinking.

Participants in Clear Sky’s journalism workshop don’t shy away from tough subjects. The epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women in North America and the effects of gun violence on Native communities are some of themes in multimedia stories the students are developing.

“I think this is really important,” 12-year-old Chante Remle, a student at Edmonds Heights K-12, says of the workshop. “To spread, you know, awareness [about] the things people don’t really care too much about.”

Taleah Vaomu, 17, doesn’t necessarily aspire to have a career in journalism; she sees going into youth counseling as a better fit. But what she’s learned at the workshop has been no less beneficial, she says.

“It does help me out with school and everything,” says Vaomu, soon to be a senior at the Muckleshoot Tribal School in Auburn. “There’s a lot of things I could take in that I wouldn’t really know until later on in school. So … if I go back into school, I can be like, ‘Oh, I know this, or know this’ and things like that.”

Before the youth complete their own, collaborative stories, they go through a crash course on journalism ethics and principles: what does it mean to present information fairly, how do you separate fact from fiction and how do you approach difficult subject matter in your reporting?

A 2015 study in the Journal of Media Literacy Education suggests that adolescents who demonstrate higher news literacy — marked in part by a keen understanding of current events and a greater scrutiny of news sources — tend to be more selective and proactive about the news they consume. That is to say, they are better able to filter news in a useful way.

The days of readers flipping through broadsheets and tabloids are dwindling. Young people, like the workshop students, are overwhelmingly getting their news from nontraditional platforms such as Instagram, YouTube and Snapchat.

“You can find out information about people in places you’ve never been to, you might never go to,” Rios tells them. “But you’re able to access that information like never before.”

But with that boundless access to information comes a greater responsibility for separating fact from fiction, he points out.

“There’s a lot of blurred lines between what is news and what is not news,” Rios says, asserting how quickly false news stories can pick up steam on social media.

A key element of the workshop is teaching students how to discern the veracity and bias of the content they engage. They also learn interviewing techniques and how to compile research from literary sources.

Upon successful completion of the workshop, which is sustained through grants from King County and the Discuren Charitable Foundation, the participants will receive a $500 stipend.