By MIKE DUNHAM

mdunham@adn.comJune 1, 2014

As an artist, collaborator and conservator, Tlingit master carver Tommy Joseph has been involved with many of the most important totem projects in Alaska over the past 20 years.

The short list includes the Indian River History Pole carved with Wayne Price, the Kiks.adi Memorial Pole and the much-photographed “Holding Hands” Centennial Pole, all in Sitka National Historical Park.

But the soft-spoken artist will address the brutal arts of war at the Anchorage Museum on Thursday, specifically the battle armor and weapons of the Tlingit Indians. It’s a subject he’s devoted special attention to over the last few years.

Joseph’s totems can be found in England, New Zealand, at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh and in front of the Department of Veterans Affairs homeless shelter at Benson Boulevard and C Street in Anchorage.

One of the recent generation of artists finding new ways to explore totemic forms, he often incorporates unexpected or modern elements in his work. On a pole for the Family Justice Center in Sitka, there are young people wearing contemporary clothing. A rainbow is featured on the “Good Life” pole created for Sitka’s Pacific High School. A camera shutter can be discerned on the pole honoring the late Japanese photographer Michio Hoshino. Multicolored hands decorate his Census Pole, created to encourage participation in the 2010 U.S. census and which traveled across the state.

It may seem like a leap to go from items now considered ornamental — bowls, blankets, totem poles — to devices meant for killing. But before contact, Native Alaskans expected all tools to be both functional and decorated. War equipment was considered especially important and was especially well-decorated.

Joseph said he started to “seriously research” Tlingit battle gear in 2004, the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Sitka between the Russians, led by Alexander Baranof, and the Kiks.adi clan, led by Chief Katlian.

“There wasn’t a whole lot available online or in books,” Joseph said. “So I decided to do the research myself.”

He began with the collections at the Sheldon Jackson Museum in Sitka, where the raven-shaped battle helmet worn by Katlian in the fight against the Russians is kept, and the Alaska State Museum in Juneau. He got a grant to explore the holdings at the Burke Museum in Seattle. Then a Smithsonian fellowship that let him look over items held in several East Coast museums.

An award from USA Artists let him travel to Europe, where he visited the British Museum, several Russian museums and “I’m not sure how many museums in Paris.” He photographed the pieces, examined them and “picked ’em apart in my mind.”

With an individual artist grant from the Rasmuson Foundation, he re-created the weapons and armor he’d studied and mounted a solo show at the Alaska State Museum in Juneau last year. “Rainforest Warriors” featured six mannequins in full battle gear along with assorted artifacts and paintings.

The traditional war equipment in Southeast Alaska bears a striking resemblance to that worn by the ancient Greeks as described in Homer’s “Iliad.” Fighting was close and hand-to-hand, with copper knives the primary tool. The blades jutted forward and backward, Joseph said, and were held in the middle. In place of a second blade, some of the knives had a blunt pummel, often carved in the form of an animal head.

Other weapons included copper-tipped spears, war clubs with heavy bone heads and nasty-looking, laboriously carved jade spikes up to 16 inches long.

“They were like a miner’s pick,” he said, “for whacking skulls.”

Wood and leather served for armor. The most prominent piece — the one most commonly displayed in museums — was the helmet, often decorated with a human or animal face. It came down to the eyebrows. A bentwood neck collar was attached to the rear of the helmet and held in place with a mouthpiece clinched in the teeth.

The body was protected with the heaviest of hides — moose, bear or sea lion, sometimes in multiple layers. Joseph has seen examples with hides as much as a half-inch thick. “It was like our modern day Kevlar,” he said. Vertical wooden slats were strapped to the leather, typically in top and bottom halves, some reaching halfway down the warrior’s legs, which could also be guarded with slat leggings.

Musket balls could bounce off such armor, Joseph said.

Joseph said some of what he discovered in his research came as a surprise.

“We were told that war helmets were always, always made from a spruce burl,” he said. The rock-hard knot is difficult to split even with a maul. “But I found some that were made from straight grain — and some were maple,” a non-Alaska wood that would have been acquired via trade with tribes in present-day British Columbia or Washington.

“One that really surprised me was made of red cedar,” he said. “That’s a soft wood.”

The maker of a cedar helmet covered it with animal hide, however, to reinforce it, much as modern plastic-foam bike helmets are sometimes covered with a light nylon skin.

Joseph was born in Ketchikan in 1964 and has lived in Sitka for most of his life. He said he became interested in traditional art when a carver presented a workshop on making halibut hooks for his third-grade class.

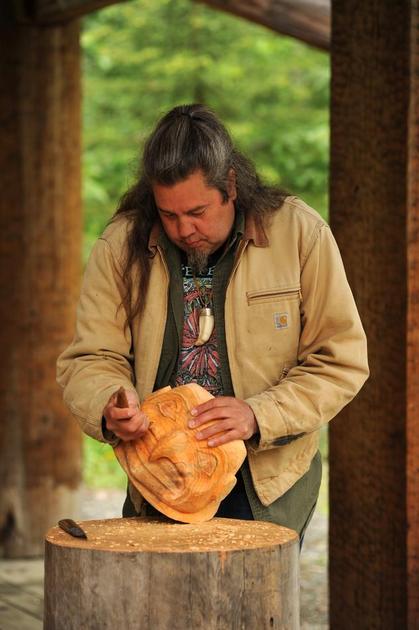

Last week it was Joseph who was teaching apprentices how to make such hooks at the Alaska Native Heritage Center. He was also working on a new war helmet at the center’s Southeast site.

After his talk about battle gear this week, he’ll stay in Anchorage to do conservation work on one of his poles that recently came into the museum’s possession.

He doesn’t often come to Anchorage. Only coincidental gaps in timing with various other projects permitted him to make an extended visit this year. Among other things, his Sitka studio, Raindance Gallery, is slated for expansion, in part to accommodate the popular workshops he conducts there.

And yes, if you need a Tlingit war helmet, you can buy one at the gallery. Though his in-depth study of Tlingit weapons is only about a decade old, they’ve been an object of artistic interest for some time.

The Kiks.adi pole, for instance, carved in 1999, has a frog at its base, the clan symbol of the Tlingit leader Katlian. The frog appears to be holding a raven in its lap.

A closer look shows that it’s a replica of Katlian’s helmet.

Reach Mike Dunham at mdunham@adn.com or 257-4332.