An intersection of domestic violence and the MMIW movement

By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

As October comes to an end, so does Domestic Violence Awareness Month. However, the reality for Native American women around the country is domestic violence isn’t simply a notion only worth paying attention to in October. It’s much, much more than that. It’s a historical trauma that plagues our life bearers every single day.

Abuse and mistreatment of Native women has garnered recent attention in mainstream news outlets since Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland took office and placed a spotlight on the national crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW). A foreign concept to the vast majority of non-Native citizens, the MMIW movement isn’t new. It’s innately tied to each of the 574 federally recognized tribes through blood, tears, and loss.

The National Crime Information Center reports that, in 2016 alone, there were 5,712 reports of missing Native American women and girls. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention has reported that murder is the third-leading cause of death among Native women and the rates of violence on reservations can be up to ten times higher than the national average. Despite this ongoing crisis, there is a lack of data and an inaccurate understanding of MMIW.

In her Washington D.C. role, Secretary Haaland has made it a personal mission on behalf of Native America to pursue justice. Earlier this year she announced the Not Invisible Act to increase intergovernmental coordination to identify and combat violent crime against Natives and within Native land. The bill was passed unanimously by voice vote in both chambers of Congress.

“A lack of urgency, transparency, and coordination has hampered our country’s efforts to combat violence against American Indians and Alaska Natives,” said Secretary Haaland. “In partnership with the Justice Department and with extensive engagement with Tribes and other stakeholders, Interior will marshal our resources to finally address the crisis of violence against Indigenous peoples.

“We’ve had missing and murdered Indigenous people for the last 500 years. This is an issue that’s been happening since the Europeans came to this continent and began colonizing Indigenous people,” she added.

While the Not Invisible Act and corresponding formation of a new Missing and Murdered Unit within the Bureau of Indian Affairs are intended to provide critical leadership and direction for interagency work involving MMIW, it brings little comfort to those who’ve lost loved ones. Nothing will undue the violence and untold traumas inflicted upon our Native women.

But if silence promotes violence, then creating a platform of understanding about the intersection of domestic violence, something that is well known in the mainstream, and the MMIW movement can ultimately prevent trauma while amplifying voices that have been silence for far too long. Tulalip tribal member Malory Simpson, a domestic violence survivor, agrees with this sentiment.

“There is an overlap between Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and domestic violence because the manipulation that happens when you are in that place is unreal,” explained Malory. “It can be crippling depending on the severity of the abuse. You can be isolated and mentally beaten down to where you do not want to reach out and ask for help and that’s where the abusers want you to be. Alone, isolated, afraid and all theirs.

“MMIW continues to be an ongoing issue in Indian Country because abusers are allowed to get away with perpetrating violence, up to and including murder, on Native women and get away with it due to jurisdictional restraints by law enforcement,” she added.

In her position as training coordinator for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Malory was especially open and honest about her past experience with domestic violence during October. She routinely posted on social media about it and offered resources for those who may be suffering in silence.

“I find it important to share my story because that was a huge part of my own healing journey,” she said. “I used to be worried about what others would think, like thoughts of guilt or shame, but really nothing compares to the relief of opening up about your situation. There are so many in our community who will wrap you with support, and the Tribe has resources to help. I share my story now in the hopes of empowering anyone who is in a similar situation to find the strength to leave, or to at the very least reach out for help.”

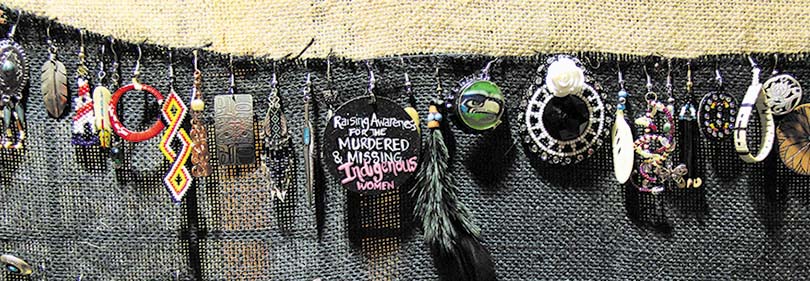

Symbolizing the intersection of domestic violence and the MMIW movement is a travelling art exhibition titled Sing Our Rivers Red. The exhibit aims to be bring awareness to the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and colonial gender based violence in the United States and Canada.

Created by Navajo and Chicana artist Nani Chacon, her travelling exhibition uses thousands of single-sided earrings to represent the Indigenous women reported murdered and missing every year. Nani’s intention is to use the power of art to raise awareness about this epidemic that occurs in the United States and all across Turtle Island. Over 3,406 earring were donated from over 400 people, organizations, groups, and entities from across 45 states in the U.S. and six provinces in Canada.

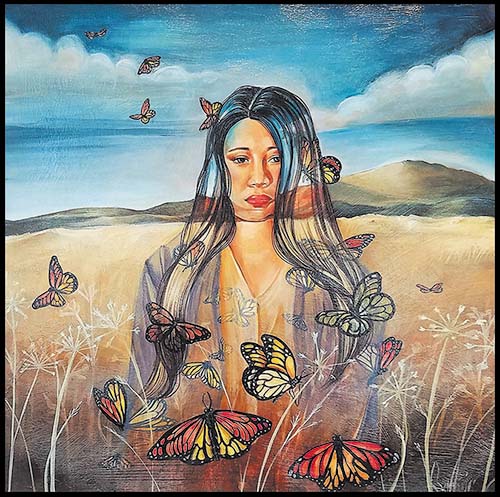

Accompanying the waves of earrings is a stunning oil painting titled Missing. Nani explained, “I created this piece to honor the lives and memory of unexplained murders and missing Indigenous women of North America. The imagery I chose places a woman amongst a landscape and butterflies.

“The interaction of the woman and the butterflies has little do with one another in the physical sense; instead, I combine the elements in this painting in an overlapping manner to create cohesion between three violated subjects. The butterflies are a symbol for Indigenous women, which is why they are seen moving through and within the woman. The monarch butterfly has a migratory pattern that spans North America. In recent documentation, the monarch butterfly is also unexplainably dying / missing.

“In this piece, I wanted to depict the connection between land and women – I see that we are mistreating and killing both. I believe that because there is no respect for the land, there is no respect for women. I believe when one stops, the other will too.”

Sing Our Rivers Red recognizes that each of us has a voice to not only speak out about the injustices against our sisters, but also use the strength of those voices to sing for our healing. Water is the source of life and so are women. We are connecting our support through the land and waters across the border: we need to “Sing Our Rivers Red” to remember the missing and murdered and those who are metaphorically drowning in injustices.