By Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

In the heart of Washington D.C. is the world’s largest museum complex, known as the Smithsonian Institution. Among the many museums, libraries and research centers that make up this diverse information paradise is the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI).

According to the museum’s website, NMAI cares for one of the world’s most expansive collections of Native artifacts, including culturally significant objects, photographs, treaties, and media covering the entire Western Hemisphere. From its indigenous landscaping to its wide-ranging exhibitions, everything is designed in collaboration with tribes and tribal communities, giving visitors from around the world the sense and spirit of Native America.

“I feel a profound and increasing gratitude to the founders of this museum,” said museum director Kevin Gover (Pawnee). “We are here as a result of the farsighted and tireless efforts of Native culture warriors who demanded that the nation respect and celebrate the contributions that Native people have made to this country and to the world.”

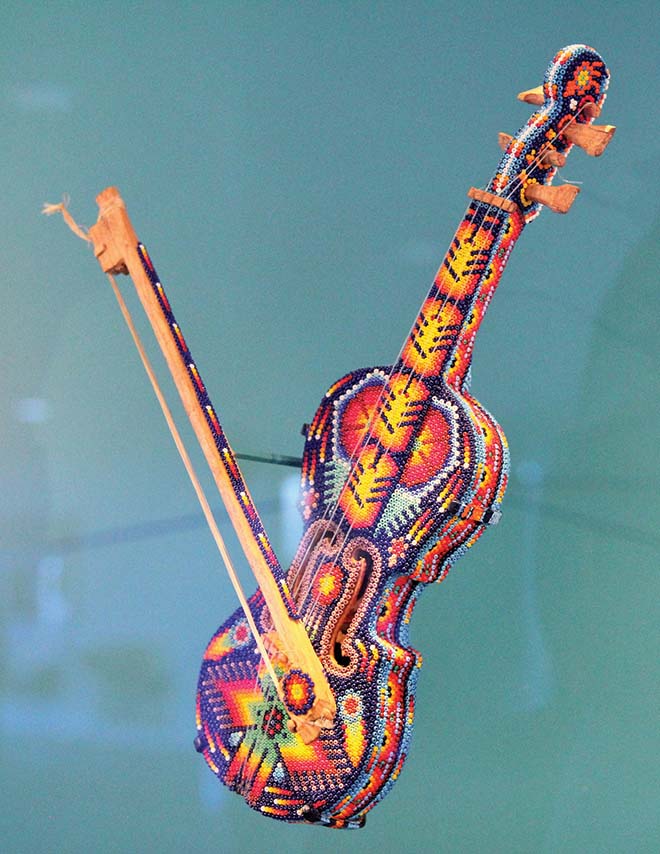

Jalisco or Nayarit State, Mexico

Wood, glass beads, beeswax, vegetal fiber and nylon monofilament.

Beadwork

The earliest beads were made from shell, stone, bone, ivory, and seeds. By 1492, Venetian factories were producing glass beads that early explorers and traders carried all over the world. Native people saw brightly colored glass beads as prized possessions and eagerly traded for them. Large “pony beads” are found on Great Plains clothing before the 1850s. The tiniest beads, called “seed beads,” become popular after about 1855.

Beads could be worn as necklaces, stitched to clothing, or woven into strips. They often replaced earlier decorative materials such as porcupine quills or painted designs. Since women learned beadwork from their elders, clothing and other items often matched distinctive traditional tribal styles.

Color preferences, influenced by the symbolic meanings ascribed to certain colors, varied regionally. In the western Arctic, for example, blue beads were thought to have great cultural importance.

Today, beadwork continues to delight us, with both women and men creating traditional clothing and regalia as well as innovations such as beaded neckties, baseball caps, and high-top sneakers. All are worn by both Native people and non-Native admirers of this unique American creation.

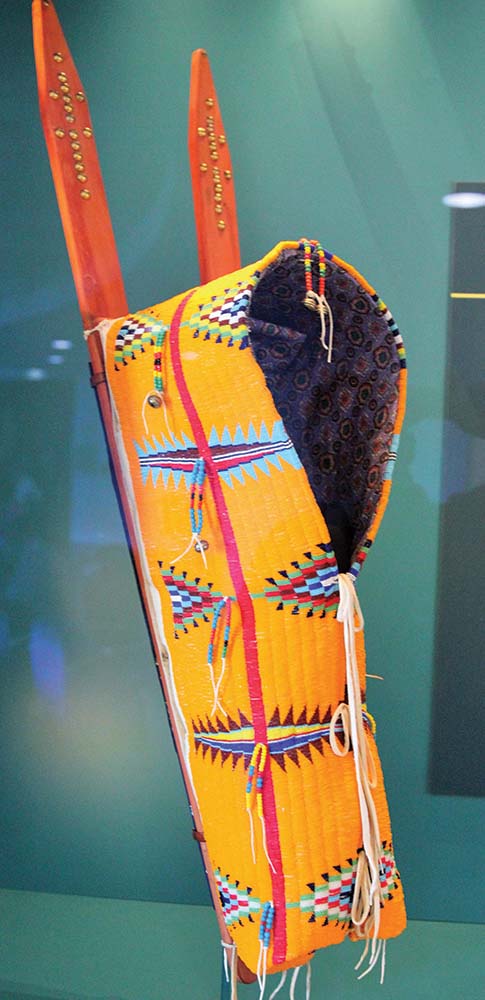

Ardena M. Whiteshield (Cheyenne), 1939-2001

Wood, glass beads, hide, metal tacks and cotton cloth.

Native Glass

In the early 1960s, innovations in glass furnaces brought glass-blowing out of the industrial settings and into individuals studios and workshops, as well as Native art schools. Since then, dozens of Native artists have created works in blown, cast, etched, fused, and electroplated glass, stretching the boundaries of Native Art.

Emil Her Many Horses (Oglala Lakota)

The sun figures prominently in Native American ceremonies, creation stories, and art. This sculpture is based on the Tlingit story, “How Raven stole the Sun.” In the story, Raven releases the sun and the moon from boxes held by a chief. This gives light to the people and created day and night.

Wood, feathers, paint and cotton string.

Kuskokwim River, Alaska

Yup’ik people used masks as prayers to ask for what they needed, including good weather and plenty of animals to hunt. This mask was intended to heal someone who was sick.

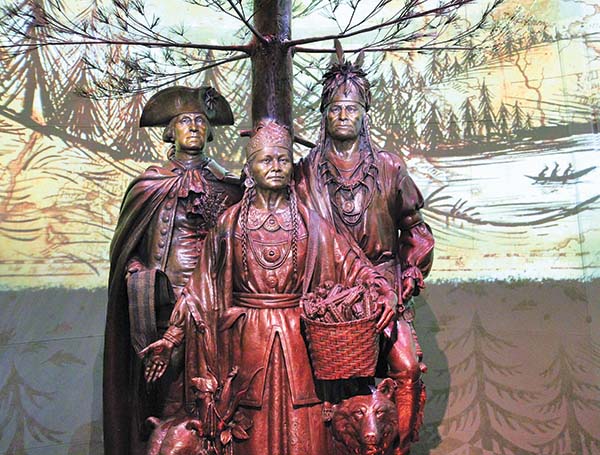

Edward E. Hlavka (Oneida Nation)

This bronze statue honors the alliance between the Oneida Indian Nation and the United States during the American Revolution. General George Washington stands alongside the Oneida diplomat Oskanondonha and Polly Cooper, an Oneida woman who came to the aid of Washington’s starving troops at Valley Forge in 1777-78.