By Kalvin Valdillez, Tulalip News

On display in public buildings throughout the Tulalip Reservation are beautiful works of traditional Tulalip art. Paintings, drums, paddles, masks and carvings created by Tribal artists cover the walls of government offices and local schools. Some of those establishments are also home to large wooden sculptures carved from cedar that depict insightful stories passed through the generations, many welcoming guests to their space of business, healing or learning. At certain places, such as the Tulalip longhouse, you may even spot a carving with a family crest or symbol in the design.

“There are several different types of poles,” said Tulalip Carver, Tony Hatch. “Story poles, house posts, spirit poles, family crest poles. There’s clan poles; if you belong to a bear, wolf, seal, otter clan, they all have their own symbol and that’s what they put on their house posts. The house posts are the ones you see if you went into our longhouse, on the inside. Each one of those poles mean something different.”

The Tulalip people have a long, rich history with the cedar tree. For centuries, the Tribe’s ancestors utilized the tree’s resources by carving canoes, paddles, rattles and masks as well as weaving baskets, headbands and clothing from the sacred cedar. Although today Indigenous art is admired for its beauty from an outsider’s perspective, most pieces were intentionally created as tools for everyday necessity and for cultural and spiritual work.

Family and clan crests have been carved into house posts since time immemorial, specifying designated areas at the longhouses. An easy-to-spot indicator of a house post is the grooved indent at the top, intended to support the beams of the longhouse as house posts were initially a part of the building’s infrastructure. House posts are a common carving amongst Northwest tribes and can be viewed in person at a number of locations on the reservation such as the Hibulb Cultural Center, the Don Hatch Youth Center and the Tulalip Longhouse.

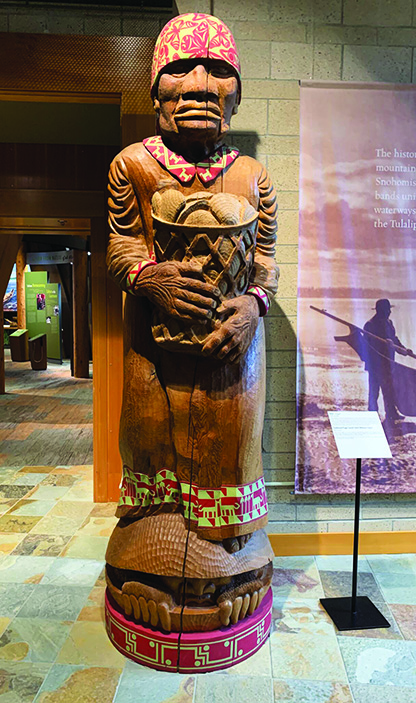

Also widely constructed by the tribes of this region are welcome poles. These sculptures are generally placed at the entrance of buildings, extending a friendly invite to visitors. They typically feature an Indigenous person in the design, highlighting a certain aspect to the tribal way of life. Welcome poles are prominent throughout Tulalip, with pieces at the entrance of the Tulalip Administration Building and the Betty J. Taylor Early Learning Academy.

“Those are storytelling poles at Early Learning,” stated Tulalip Carver, Steve Madison. “We put those there for a purpose, for the little kids. The poles are carved in the shape of a salmon. On the salmon there’s a woman and a man and they are both storytellers. That’s why they were carved, so our kids will always know the stories about our people, the salmon. Because the salmon encompasses the spirit of our people.”

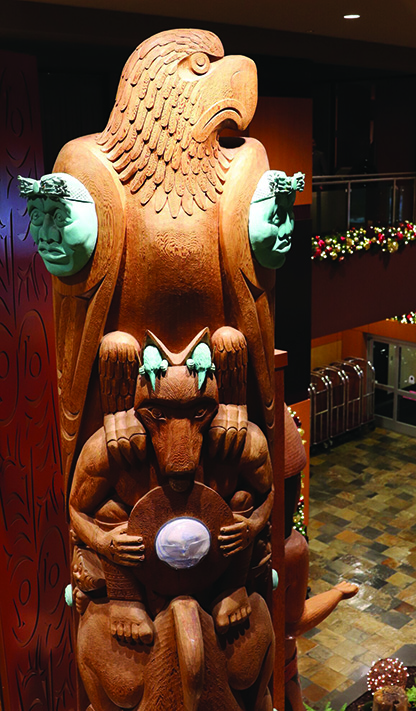

Perhaps the most recognizable welcome pole is the monumental post, created by Joe Gobin, which stands in the lobby of the Tulalip Resort Casino. With arms reaching out to the people, the pole welcomes newly arrived guests to the elegant hotel; a great photo opportunity for those receiving the Tulalip experience for the first time. Located directly at each side of the welcome pole are two story poles; a gambling pole representing the traditional game of slahal, also created by Joe Gobin, and a story pole that features an eagle and a seawolf designed by James Madison.

“There’s differences between house posts and story poles,” explains James. “A lot of people don’t know where a totem pole came from, or a story pole. They don’t know that we didn’t do that here, traditionally. But we continue it because William Shelton created it for our people, to keep our culture alive. They’re the stories of our families, about our people, and they hold the information of who we are and what our people went through; the history, knowledge and spiritual side of it. Joe Gobin and I decided to follow that William Shelton look but modernize it, refine the carvings and bring it up to date. You’ll see that high relief in our carvings. It’s a unique style and something that Shelton created, he was a pioneer in that way. It’s our way to pay respect to him as a carver.”

At a time when the Indigenous population was enduring assimilation efforts by the U.S. government, the last chief of Tulalip, William Shelton, made it his mission to preserve the traditional Salish way of life. By cunningly requesting approval to formally honor the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliot, Shelton received permission to construct the Tulalip Longhouse on the shore of the bay. Due to his dedication, the people were able to gather once a year at the longhouse to take part in a night of culture as well as reflect and continue the teachings of those ancestors who came before them.

Drawing inspiration from Alaskan Natives, as well as incorporating his own heritage, Shelton created the very first story pole in 1912 that was later erected at the Tulalip boarding school in 1913. The unique pole caught the attention of the masses and Shelton story poles began to pop up in local communities. The city of Everett, Seattle Yacht Club, Washington State Capitol, Woodland Park Zoo, and a number of parks throughout the nation commissioned his story poles and as time moved forward, colonizers eventually switched from condemning Native artwork to collecting it and his work was in high-demand.

In 2013, a William Shelton story pole returned to the Pacific Northwest after standing at Krape Park in Freeport, Illinois for almost seventy years. The pole was taken down due to damage from weather over the years and the thirty-seven foot pole was sent to the Burke Museum. Today, the pole is in possession of the Burke and contained in storage off-site with plans of restoration in the near future.

“The William Shelton story pole is an important piece of Salish, and more specifically, Tulalip history,” explained Kathryn Bunn-Marcuse, Burke Museum Curator of Northwest Native Art. “Shelton’s story poles brought oral histories and valued stories into monumental form, anchoring Tulalip history into these permanent markers. He did this during the years in which governmental and educational policies were aimed at erasing Indigenous languages, customs, and knowledge.”

In his lifetime, Shelton constructed a total of sixteen story poles that were raised at various locations to help educate newcomers about Tulalip culture. His efforts helped bridge the gap between Natives and non-Natives. Shelton found ways to feed the non-Indigenous population knowledge about the heritage of his people in small doses, subtly squeezing in traditional stories, language and songs through his art. In addition to the story poles, Shelton gifted the world two publications and a better understanding of the Coast Salish lifeways.

Tessa Campbell, Lead Curator of the Hibulb Cultural Center has been on the search for Shelton poles since the museum’s opening. Tessa and her team have recovered and restored, or are in the process of restoring, several poles after successfully tracking them down through Shelton’s correspondence letters. Unfortunately, due to decades passing by, a few poles were taken down, only to never be seen again. However, she intends to continue pursuing the poles until all sixteen are accounted for.

“We credit William Shelton for coming up with the idea of the story pole,” Tessa expressed. “There weren’t story poles around before William Shelton, but there were welcome poles and house posts. He saw the story pole as a way to preserve our history. I compare it to a book; people preserve their family history by writing, he did it through carving. For his first pole, he went to the elders and got their stories, and he carved each story into the pole. So, each figure is like a chapter of a book.”

Another set of carvings that held significant value to the people of Tulalip were the gateway poles. Over forty years ago, the entryways to the reservation were marked by two story poles and connected by a canoe carving overhead. Now fondly missed by the older generations of the community, the carvings were cut down by non-Natives of neighboring towns who were upset with the Boldt Decision in 1974.

“I remember my grandpa (Frank Madison) used to talk about the poles that were out here, the two upright poles and a canoe over the top and everyone used to drive underneath it,” James reflects. “That was an identifiable icon for our tribe way back when. A long time ago, something happened between the people of Marysville and some people of Tulalip. The Marysville people came over and chopped it down with a chainsaw. It’s a harsh story but its history – it’s what happened. I always had that story in the back of my mind. My grandpa always wanted to recreate it. I’m on that same path, so hopefully some day they let me recreate that out of a different material, out of bronze or cement. That way our people can have that to be proud of because we were all raised knowing that arch was there back in the day, the two of them one at the beginning of the rez and the one at the end.”

William Shelton and every Tulalip artist since his time have excelled at preserving and continuing their ancestral teachings. By passing on the tradition and the knowledge that comes with it, they have carved quite the story for the future generations of Tulalip as well as the history of the generations who came prior.

“Starting the little ones out while they’re young is important,” said James. “People like me; we don’t know any different. I was doing this before I can remember. Starting the youth early is important to keeping this part of our culture alive. Anybody can just pick it up and learn, but the knowledge of the work to go along with the skill is important. I was very fortunate to have my grandpa and my dad there to teach me that information. Honestly, you can teach anybody to carve or draw, but it’s the information that goes with it, putting your spirit and soul into it, making it come alive, making it Indian – that’s what I think is important.”