by Micheal Rios, Tulalip News

Traditional ceremonial practices and art-making are imbedded in all Native cultures. These fundamental Native aspects continue today much as they did in the past, and new forms have evolved in response to social changes, new markets, and a desire for personal expressions. The resurgence of canoe carving teaches youth how to strengthen body and spirt by working together, while increasingly, Native foods are used to combat modern diseases. Artists today have important dual roles of creating works for their community and for family celebrations, but also for public art, private patrons, art gallery sales and museum displays.

For the last three months, the greater Seattle area had the opportunity to see some of the most stunning works of Native American art that has been produced as a result of those traditional ceremonial practices of long ago and the modern day interpretations that combine the traditional with contemporary design. The ‘Indigenous Beauty’ exhibit on display at the Seattle Art Museum held masterworks of Native American art. Those who were able to visit the museum and explore the exhibit marveled at nearly 20,000 years of amazing skill and invention. Museum patrons lingered over paintings, sculptures, baskets, beaded regalia and masks.

The immense variety of ‘Indigenous Beauty’ reflects the diversity of Native American cultures. Deeply engaged with cultural traditions and the land, indigenous artists over the centuries have used art to represent and preserve their ways of life. Even during the 19th and 20th centuries, when drastic changes were brought by colonization, artists brilliantly adapted their talents and used the new materials available to them to marvelous effect.

The works in ‘Indigenous Beauty’ inspire wonder, curiosity and delight. In an effort to share those feelings of admiration and amazement that stem from viewing the culture and history that was on display from February 12 to May 17, the Tulalip See-Yaht-Sub offers its readers a sample of the exhibit.

The objects on view in this exhibition reflect a wide breadth of indigenous history and artistry from the past 250 years, from the Columbia River to Southeast Alaska. The Seattle Art Museum is grateful for the generosity of the indigenous artists and their willingness to share their collections.

Glass Chest, 2005 (top left). For hundreds of years, cedar chests have been made by steaming and skillfully bending a plank of cedar to create the four sides of the container. A separate bottom and top are then added, and formline designs representing natural forms such as bears, ravens, eagles, orcas and humans; legendary creatures such as thunderbirds; and abstract forms made up of the characteristic Northwest Coastal shapes dramatically embellish the four sides of the chest. Wood chests were used to store valuables, serve as a royal seat for a chief, or even act as a repository for his remains after death.

This spectacular example is a very contemporary version made using cast and sand-carved techniques by Preston Singletary (Tlingit, born 1963), an innovative Tlingit artist who was the first to render one of the ancient designs in glass. Singletary’s glass chest retains the essence of an ancient art form and signals his participations in a larger community of contemporary art.

Frog Feast Bowl, 1997 (page 8 bottom) Preston Singletary worked at Pilchuck Glass School, an international center for glass art education, for thirteen years where he studied with Dale Chihuly. His work is renowned for incorporating Northwest Coast design into the non-traditional medium of glass, synthesizing his Tlingit cultural heritage, modern art, and glass into a unique blend all his own.

Indian Warrior, 1898 (page 8 top right)A westerner by birth, Alexander Proctor (1860-1950) earned an international reputation as one of the most accomplished sculptors of his generation. This parlor sculpture was Proctor’s response to the equestrian statues that were typically favored by 19th-centure Americans. Proctor imagined a great Native leader. While on the Blackfeet reservation in Montana, he modeled the figure from a Blackfeet warrior, a man who conveyed elegance, fleetness and dignity. His heroic subject, cast in bronze in Paris, won the twenty-seven year old Proctor a gold medal at the International Exposition of 1900.

Thunderbird mask and regalia, 2006. Wood, paint, feathers, rabbit fur and cloth by Tlasutiwalis Calvin Hunt, Kwagu’l born in 1956. “In the myth stories in our culture, we believe that the animals and the birds can take off their cloaks and transform into human beings.” – Calvin Hunt.

Killer Whale, 2003. Fused and sand carved glass by Preston Singletary, Tlingit born 1963. In this, his first monumental work, Singletary fused his clan Killer Whale crest into sixteen panels, recharging an ancient tradition and bringing the past forward.

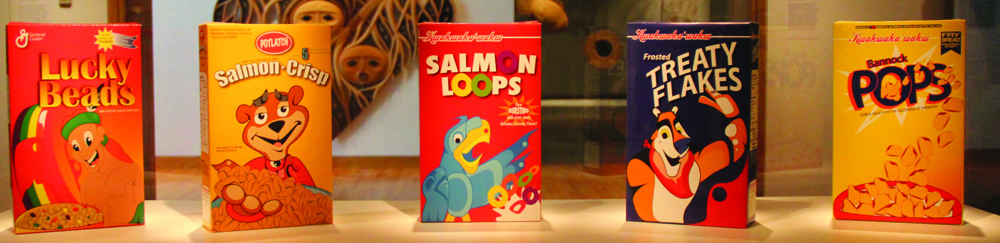

Breakfast Series, 2006. Sonny Assu’s (Southern Kwakwaka’wakw born 1975) ‘Breakfast Series’ appropriates the form of the familiar cereal box and decorates its surfaces with commentary on highly-charged issues for First Nations people – such as the environment, treaty rights and land claims. The pop art-inspired graphics on the five boxes in the series contain recognizable imagery, but upon closer inspection we see that Tony the Tiger is composed of formline design elements, the box of Lucky Beads includes a free plot of land in every box, and contains “12 essential lies and deceptions.” The lighthearted presentation, upon further investigation, exposes serious social issues.

Contact Micheal Rios, mrios@tulaliptribes-nsn.gov