(Part One of a Four-Part Series)

By Kyle Taylor Lucas for Tulalip News

This is the first story in a series exploring the study of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) and the intersection of chronic health and addiction issues among American Indians. The series focuses upon contributing factors of disproportionately high ACE numbers in American Indians to disproportionately high substance abuse and behavioral and physical health issues. The underpinning historic, social, legal, political, and economic realities of American Indian tribes and members are ever present.

The ACE scientific breakthrough unexpectedly originated with an obesity clinic led in 1985 by Dr. Vincent Felitti, chief of Kaiser Permanente’s Department of Preventive Medicine, San Diego. He was mystified that over a five year period, despite their desperate yearning to lose weight, more than half of his obese patients dropped out. Then, in conducting interviews with those patients, he was shocked to discover that the majority had experienced childhood sexual trauma. That led to 25 years of research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente’s San Diego program. Their research resulted in a study that revealed adverse childhood experiences are strongly linked to major chronic illness, social problems, and early death.

According to the CDC, “the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study is one of the largest investigations ever conducted to assess associations between childhood maltreatment and later-life health and well-being.” It includes more than 17,000 Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) members who upon “undergoing a comprehensive physical examination chose to provide detailed information about their childhood experience of abuse, neglect, and family dysfunction. To date, more than 50 scientific articles have been published and more than 100 conference and workshop presentations have been made.”

The ACEs study considered three types of abuse–sexual, verbal and physical; five types of family dysfunction (mentally ill or alcoholic parent, mother as victim of domestic violence, an incarcerated family member, and loss of a parent through divorce or abandonment); and added emotional and physical neglect for a total of 10 types of adverse childhood experiences or ACEs. These are the ten categories utilized in today’s screening.

The CDC’s study uses the ACE Score, which is a total count of the number of ACEs reported by respondents. The ACE Score is used to assess the total amount of stress during childhood and has demonstrated that as the number of ACE increase, the risk for the following health problems increases in a strong and graded fashion:

Alcoholism and alcohol abuse

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Depression

Fetal Death

Health-related quality of life

Illicit drug use

Ischemic heart disease (IHD)

Liver disease

Risk for intimate partner violence

Multiple sexual partners

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs)

Smoking

Suicide attempts

Unintended pregnancies

Early initiation of smoking

Early initiation of sexual activity

Adolescent pregnancy

The CDC said, “It is critical to understand how some of the worst health and social problems in our nation can arise as a consequence of adverse childhood experiences. Realizing these connections is likely to improve efforts towards prevention and recovery.”

The ACEs study and others specifically focused upon the American Indian community provide information and support for those struggling to overcome ACEs by building resilience–competencies and supports that enable individuals, families, and communities to recover from adversity.

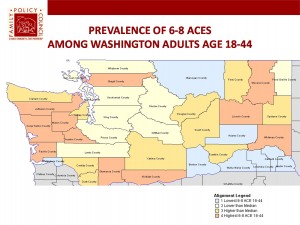

A 2009-2010 statewide study of the Prevalence of 6-8 ACEs among Washington adults ages 18-44 found ACEs to be common among Washington adults with 62 percent having at least one ACE category, 26 percent having 3 categories; and 5 percent having 6 categories. Of interest to Tulalip, the study found Snohomish County among the group scoring two lower than the median.

State research shows part of the key to overcoming ACEs is building both individual and community resiliency and some have suggested a move from technical problem solving to adaptive. Some of the discussions around improving coherence of systems will be explored in subsequent stories.

It is generally understood that ACE scores between 4 and 10 can explain why we have chronic disease or identify those at risk for developing chronic diseases. It’s been said that knowing our ACEs score is as important as knowing our cholesterol scores. Knowing can help us take steps to change or prevent behavior likely to result in disease and it can help us to prevent it in our children as well to ensure their healthy development. It can help communities to address often-taboo issues to begin healing from trauma as well as to build resilient communities.

An Indian Health Service (IHS) report, “Trends in Indian Health,” finds American Indians are 638% more likely to suffer from alcoholism compared to the rest of the U.S. population.It is no secret that alcohol and substance abuse is a prevalent tragic reality destroying loved ones and communities in Indian Country. Every one has been touched by its pain. Yet, despite herculean efforts to address it through a wide variety of treatment options, American Indian communities feel at a loss when traditional treatment too often fails.

According to the National Indian Health Board (NIHB), “behavioral health” is an “integrated, interdisciplinary system of care related to mental health and substance use disorders that approaches individuals, families, and communities as a whole and addresses the interactions between psychological, biological, socio-cultural, and environmental factors.”

In recent years, there has been a general shift toward more holistic treatment of health issues; but, particularly in Indian Country with a prevalence of multigenerational trauma issues, practitioners find it more effective. American Indians struggling with addiction and/or mental health issues generally find the infusion of traditional cultural and spiritual practice makes treatment more accessible for them. Perhaps a basis for this is found in the relatively new science of epigenetics. Could it be that traditional treatment methods are especially insufficient for American Indians?

In the report, “A Framework to Examine the Role of Epigenetics in Health Disparities among Native Americans,” the authors affirm, “Native Americans disproportionately experience ACEs and health disparities, significantly impacting long-term physical and psychological health.” In addition to these experiences, the persistence of stress associated with discrimination and historical trauma converges to add immeasurably to these challenges.” [Teresa N. Brockie, Morgan Heinzelmann, and Jessica Gill, “A Framework to Examine the Role of Epigenetics in Health Disparities among Native Americans,” Nursing Research and Practice, vol. 2013, Article ID 410395, 9 pages, 2013. doi:10.1155/2013/410395]

Harvard researchers, neurobiologist Martin Teicher and pediatrician Jack Shonkoff, and neuroscientist Bruce McEwen at Rockefeller University, report, “Childhood trauma causes adult onset of chronic disease.” They determined that “the toxic stress of chronic and severe trauma damages a child’s developing brain. It essentially stunts the growth of some parts of the brain, and fries the circuits with overdoses of stress hormones in others.”

Washington has been a leader in research and education on ACEs on state government and foundation levels. Laura Porter, formerly served as director of ACE Partnerships for the Washington Department of Social and Health Services, but now directs the ACEs Learning Institute for the Foundation for Healthy Generations (FHG), founded in 1974. FHG, formerly Comprehensive Health Education Foundation, has a 40-year history of providing social and emotional learning tools in schools to prevent youth substance abuse, support self-esteem, anti-bullying and other kinds of related social-emotional tools for teachers. This past year, the board decided to include ACEs in its strategic plan and hired Porter to direct the program.

Porter oversees analysis of ACEs & resilience data and works with local and state leaders to “imbed developmental neuroscience and resilience findings into policy, practice, and community norms.” It would be exciting to see some coordination with tribes whose members are disproportionately affected.

This past year, Porter conducted a webinar on the “Science of ACEs and the Potential Role of Public Health in Addressing Them.” She found that only about one-third of her audience had an ACE-informed public health initiative. She hopes to help local jurisdictions to learn how to apply the science in their work.

In her presentation, Porter explained, “Health equity occurs when the distribution of determinants of health are fairly spread across the population,” and added, “When the determinants of health are unevenly spread in ways that we could have prevented, then we have health inequity.” She argues that “ACEs are one of the most powerful drivers of health inequity of our times and maybe of all times. And for that reason, taking a public health approach is critical to solving this problem and bringing about the conditions for enduring health equity for our nation and throughout the world.”

Porter noted that the neuroscientists “working on impacts of toxic stress on development tell us that people who grew up in very dangerous periods of time have increased levels of stress hormones and neurotransmitters in their blood stream at sensitive developmental times.” Accordingly, that effects both their brain development and the expression of their genetics. That is affirmed in a new field called epigenetics. [Epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression caused by certain base pairs in DNA, or RNA, being “turned off” or “turned on” again, through chemical reactions].

According to Porter, people who grow up in adversity and a lot of danger in sensitive developmental years can generate typical kinds of characteristics. She said, “They can be more hyper-vigilant, more hyper-responsive, quick to anger, and slow to soothe. They can be very mission-focused and have a hard time taking advantage of the array of opportunities that might pop up around them. They can have a very small amount of stress and end up feeling like a major crisis in their lives. So, they’re actually responding differently to the moment by moment reality based on the adaptation they had during childhood.”

Conversely, she noted that people who grow up in very safe environments also develop typical characteristics. They might be more relationship-oriented, more likely to talk things through even when action may be more appropriate.

The important teaching from neuroscience is that both tracks are adaptations. “In both cases, people are adapting to danger or they’re adapting to a safe childhood, either way they’re helping a species to survive,” said Porter. She added, “Society has developed great accommodations for helping people who grew up in very safe environments navigate more dangerous times. We have stranger danger, we have martial arts, we have lots of public education campaigns, etc.”

Importantly, and most applicable to Indian Country, Porter goes on to emphasize that we have not yet “created the kinds of programming that can help to accommodate people who grew up in very dangerous times so they can navigate a more peaceful adulthood well. And that’s really one of the big challenges of our times, to develop those accommodations at every level of public health.”

Because American Indians are disproportionately affected by violence and the ten factors identified in ACEs, it makes sense that the community is disproportionately impacted by the related disorders.

Porter stressed the importance of looking at the determinants of health and how science is applied as well as paying attention to ACEs in terms of the life course. She emphasized the “Role of Time and the “life course approach that recognizes the role of time in shaping health outcomes.” Different kinds of supports are more meaningful in different times of life.

Photo/Julie Corley

Asked if Tulalip Tribes had conducted any research on ACEs, Sherry Guzman, Mental Health Manager in the Family Services Department, said Tulalip Tribes was one of a handful of tribes that agreed to participate in a statewide network a few years ago. She said, “Most tribes were very leery at first, but I went forward with it because I saw the value of it. It enabled me to see the difference in average of WA State versus Tulalip Tribes. I like the ACEs model because it gives a base to compare something to.”

Guzman noted that Tulalip conducted a sampling test, but the findings are clinical information, so she was unable to discuss it. However, she noted that she “was really amazed at the results,” which is not unlike responses in non-Indian communities as well.

The Behavioral Health Department is continuing its work and has scheduled an all-staff information and training session at the administration building on September 17 at 9:00 am. Asked if her department has planned any community educational sessions, Guzman said it would come later after the staff becomes better educated.

Guzman, a Tulalip tribal member, earned an MSW, and she has worked for the Tulalip Tribes for nearly twenty years, beginning on October 20, 1995. She has 8 children, 35 grandchildren, and 16 great-grandchildren. “I am very blessed,” said Guzman. Guzman added that the Tulalip Tribes are “state licensed for our chemical dependency, gambling, and mental health programs.” She noted that the department has a brochure and website that are nearly ready to be published.

As mentioned, several studies have documented the validity of ACEs testing and its value to healing in American Indian communities. Of course, privacy and anonymity must be assured.

Subsequent stories will also consider federal government obligation to American Indian health; personal interviews, treatment experts; and finally, the series will explore the potential of ACEs science and education in prevention and for building individual and community resiliency for American Indian people and tribes.

Kyle Taylor Lucas is a freelance journalist and speaker. She is a member of The Tulalip Tribes and can be reached at KyleTaylorLucas@msn.com / Linkedin: http://www.linkedin.com/in/kyletaylorlucas / 360.259.0535 cell