By Ashley Ahearn, KUOW

SEATTLE — Some bad news for backcountry in the West: Some of the fish in the region’s wild alpine lakes contain unsafe levels of mercury, according to a new study by the U.S. Geological Survey.

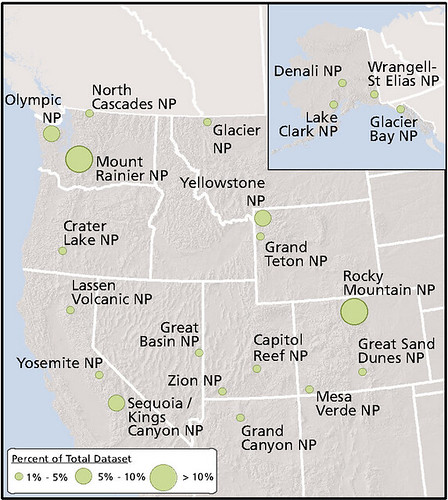

In the broadest study of its kind to date, the USGS tested various kinds of trout and other fish at 86 sites in national parks in 10 western states from 2008 to 2012. The average concentration of mercury in sport fish from two sites in Alaskan parks exceeded federal health standards, as did individual fish caught in California, Colorado, Washington and Wyoming.

But perhaps more importantly, mercury was detected in all of the fish sampled, even from the more pristine areas of the parks.

The study, conducted jointly by the National Park Service and the USGS, found that mercury levels varied greatly from park to park and even among sites within each park. Overall, 96 percent of the sport fish sampled were within safe levels of mercury for human consumption.

“It’s good news that across this entire study area most of the fish were low,” said Collin Eagles-Smith, a research ecologist with USGS and the lead author of the study. “The concern is that there were some areas, and some fish, that did have concentrations that might pose a threat to either wildlife or humans.”

Spatial distribution of the 21 national parks sampled in this

study. Size of circle represents percentage of total dataset.

Credit: USGS.

Two percent of the fish sampled in Mount Rainier National Park exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency’s guidelines for safe human consumption. Fish sampled in Olympic National Park had a higher average mercury concentration than some other parks in the region, but none of the samples were above safe human consumption levels.

“Mercury concentrations in those fish in the Pacific Northwest were quite variable,” Eagles-Smith said. “Crater Lake had quite low concentrations in comparison to other parks, whereas Olympic National Park had some of the highest concentrations in comparison to other parks.”

The researchers were surprised to find some of the highest levels of mercury in a small fish called the speckled dace, which were sampled in Capitol Reef and Zion national parks in Utah.

“The concentrations in those fish were comparable to the highest concentrations we saw in the largest, longlived fish in Alaska,” Eagles-Smith said. He added that more research is needed to better understand how mercury is deposited from the atmosphere into the environment and then concentrated at varying levels in different species.

There was some bad news in the study for birds: In more than half the sites tested, fish had mercury levels that exceeded the most sensitive health benchmark for fish-eating birds, Eagles-Smith said.

“People can regulate their intake of fish and wild fish-eating birds can’t. So, they’re going to take in more fish and more mercury as a result, and it can impact their behavior, ability to reproduce and ability to find food.”

Mercury can come from natural sources, like volcanoes. However, since the industrial revolution atmospheric mercury levels have increased three-fold because of the burning of fossil fuels. Recent studies have shown that particulate pollution from China, which could result from the burning of coal among other sources, can and does make its way across the Pacific Ocean to North America.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warns that exposure to high levels of mercury in humans may cause damage to the brain, kidneys and the developing fetus. Pregnant women and young children are particularly sensitive to the effects of mercury.