Photo by Peter van Agtmael/Magnum for MSNBC

03/24/14 msnbc.com

By Trymaine Lee

QUINTON, Okla.— “He’s still not talking yet,” said Autumn Sisco, staring down at the beefy little boy in the Buzz Lightyear sweatshirt playing at her feet. She scooped him up and swiped at his runny nose with her shirt sleeve.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with him,” she said, sinking back into her living room sofa, watching the two-year-old bounce like a pinball across the living room floor to the kitchen, down a hallway and back.

This isn’t what her life is supposed to look like. She’d imagined herself a college co-ed, partying somewhere with a drink in her hand, giggling with girlfriends, or pulling an all-nighter for an exam she didn’t study for.

Instead she’s an underemployed 19-year-old mother and wife, struggling to keep her young marriage together and raise a kid in a small rural town where opportunities are few and disappointments are many.

“Trouble,” she lamented quietly. “You’re always in trouble here. There’s nothing positive.”

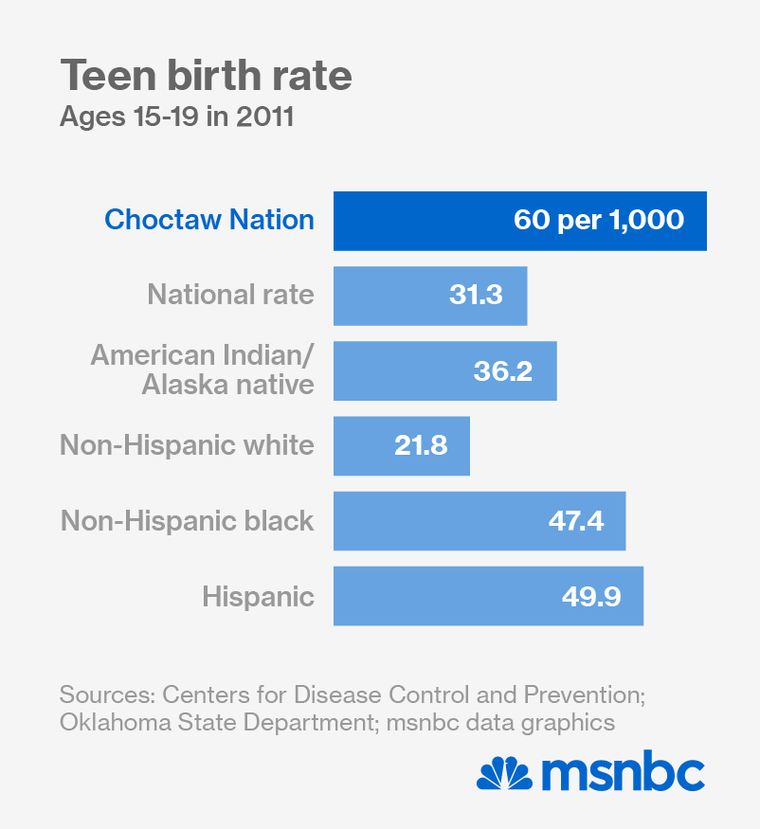

Life as a teen mom could be difficult under any circumstances. But it’s even more so here in the Choctaw Nation, a vast, rural expanse in southeastern Oklahoma where poverty and unemployment are rampant and the teen pregnancy rate is nearly double the national average.

While the teen birth rate has fallen drastically among all racial groups over the last two decades, the pregnancy rate for American Indian teens between 15 and 19 years old is 36.2 per 1,000, 15 points higher than their white counterparts and about 5 points higher than the national average, according to the Center for Disease Control. American Indian teens also lead all other groups in the rate of repeat births.

With so many young parents in the Choctaw Nation— an area larger than the state of Massachusetts— tribal leaders have made outreach to teen parents a priority. Those efforts were given a boost recently when the Obama administration designated the Choctaw Nation one of its first five Promise Zones, a program aimed at strengthening the relationship between impoverished communities and the federal government.

The tribe hopes to use the designation to access grants they’ll use to bolster some of the work they’ve already been doing, particularly around youth and families.

“What we’re doing isn’t just about changing today’s parents,” said Angela Dancer, senior director of the Better Beginnings Program, which serves at-risk and high-needs families. “It’s about changing the parents of the future.”

Dancer’s program helps ease the burdens many of these families face, including food insecurity and access to adequate medical care. The outreach workers, all of whom are Choctaw, do at-home visits and try to walk young mothers through the uncertainty of new parenthood.

They give away free diapers and car seats. And they help overwhelmed teen parents deal with stress management, create a healthy environment and teach them skills to build stronger attachments to their babies, all of which are challenges in the small impoverished communities that dot the Nation.

“They’ve had people come in and out of their lives and tell them all of the negative things about their weaknesses. But we help them understand their strengths,” Dancer said. “If we didn’t go out and touch them where they are, there’s no way we could touch as many as we do.”

But the challenges of reaching this demographic, many of whom are high-school dropouts without much financial or emotional support from their families, can often seem unsurmountable.

They’re geographically spread across very isolated communities within the nearly 11 counties that comprise the Nation’s service area. And emotionally, many are saddled with feelings of shame, guilt and the generational curse of teen pregnancy. Others are victims of domestic abuse.

“So many of them just close themselves off because they’re already worried about being judged – judged for getting pregnant in the first place,” said Hanna Wood, 29, an outreach worker who has worked with Sisco and her family.

The Nation also offers sex-education courses to schools within the Nation’s boundary, an effort that remains somewhat controversial in an area of the state dominated by conservative politics and where abstinence-only education is the preferred model. Outreach workers have found navigating the politics of teaching teens and pre-teens about safe sex and personal boundaries a delicate endeavor.

Nearly all Choctaw Indian students attend public schools where the majority of students are non-Native. And despite high rates of teen-pregnancy and a rate of sexually transmitted disease that is four times the national average, many public school districts within the Nation won’t allow the sex-ed courses taught in their schools.

For More on the Choctaw Nation see our photo essay: Hope on the Horizon for Choctaw Nation

Some schools will allow parts of the curriculum to be taught in their classrooms but won’t allow others, like condom demonstrations. On a recent evening nearly two dozen eighth graders whose school forbade such a demonstration gathered at Choctaw Nation outreach services headquarters, giggling and guffawing as an instructor urged them to slide a latex condom down their fore and middle fingers.

“We’re dealing with some pushback,” said Dancer. “But the statistics don’t lie.”

National politics have also become intertwined with the Nation’s efforts, as much of the funding for Better Beginnings is tied to the hotly-contested Affordable Care Act, aka Obamacare. Last year, sequestration cuts and a shrinking number of grants, stripped funding from many of the tribe’s critical, government-funded programs. Better Beginnings was no different.

“I don’t care about the politics of it. I’m not a political person,” Dancer said. “But that’s what my funds are tied to. If that means it gets reinstated over and over, that’s just fine by me. “

While programs to help at-risk youth in the Nation have grown from just a few 20 years ago to dozens today, there still are major gaps. The nearest substance abuse treatment facility for juveniles is nearly 300 miles away, and there’s no in-patient mental health facility or homeless shelter. And there’s still a stigma around many of the issues these young people face, a hurdle outreach workers must handle with care.

“It’s the cycle. Their mothers went through the same thing,” said Shonda Shomo, an outreach worker with the Better Beginning program. “I was a teen mom. I was 18, so I know what they’re going through. I just keep encouraging them. And that’s something they don’t always hear from their mother figures.”