By Andrew Gobin, Tulalip News

Over the last three years the Snohomish County Sustainable Land Strategy (SLS) has gained national attention for innovative planning to preserve and protect both agricultural interests and the county watershed. What started as a small project now will drive national agriculture policy. Collaborators of the SLS met with United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Deputy Under Secretary for Natural Resources & Environment, Arthur “Butch” Blazer, on January 23rd to discuss the progress of the SLS so far and their future plans. Historically, Snohomish County and area tribes have a reputation for innovative strategic planning, yet this is the first strategy that is beneficial to everyone’s interests.

The SLS is a collaborative project between the Tulalip Tribes, the Stillaguamish Tribe, and Snohomish County that “balances the need to restore vital salmon habitat while also protecting the viability of local agriculture,” according to Snohomish County’s brochure on the SLS. Salmon and farming are noted as having key roles in the history and economy of the county and can both be protected through the SLS.

Qualco Energy is one example of a collaborative effort to protect salmon habitat without burdening or infringing on agriculture. The energy company, located a few miles southwest of Monroe, is a non-profit partnership comprised of the Tulalip Tribes, Northwest Chinook Recovery, and the Sno/Sky Agricultural Alliance. In February of 2008, after 10 years of planning and research, Qualco installed an anaerobic digester that converts cow manure into energy and natural gas. Cow manure has devastating impacts on salmon habitat and typically has to be hauled away or diverted to a lagoon. Now, the manure can go right to a digester, keeping it out of the watershed without incurring time and monetary costs to farmers.

“Local communities are also happy with the reduced agricultural smells, now that the waste goes to the digester and isn’t sitting in open lagoons,” added Qualco Vice President Daryl Williams, a Tulalip tribal member who also works for the Tulalip Tribes Natural Resources department.

The Qualco example also demonstrates the support the SLS has from the state legislature. The land on which the project is located is an old dairy farm donated to the project by the state. State permitting laws were changed for the project in order to allow the project to expand to food waste, now allowing the Qualco digester to run 30% food waste without need a solid waste permit.

Co-Facilitator of the SLS, Dan Evans, said, “When you bring together the tribes and agriculture, you have tremendous bandwidth. With that, you have the key to push things through legislation,” referring to the political influence of the SLS.

That political momentum has caught the attention of the USDA, which only adds to it.

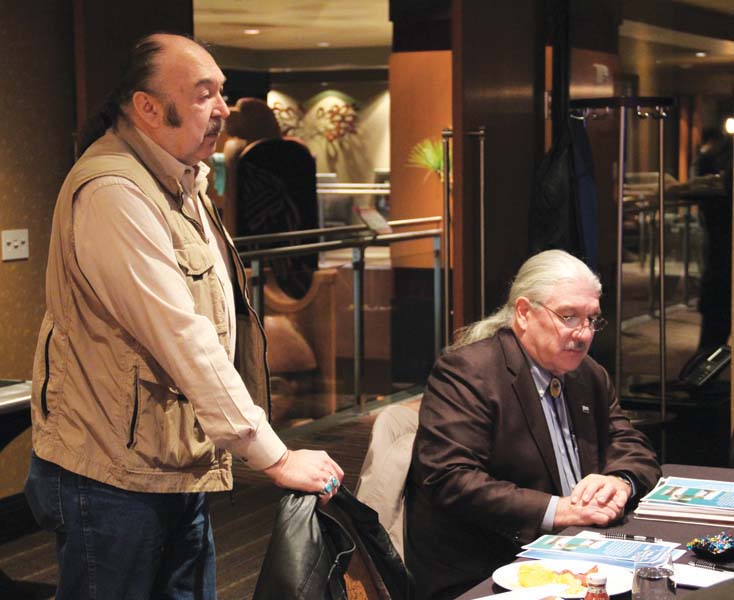

“The primary purpose I am here is to listen. This presentation is material I can take back with me [to Washington DC] and help you continue doing what you’re doing on a national policy level,” said USDA Deputy Under Secretary Butch Blazer.

The SLS has the potential to expand to other counties; Skagit and King are currently expressing an interesting in developing their own SLS.

In addition to peripheral county influence, the SLS is a gateway for future innovation in the fields of sustainable land use and clean, renewable energy.