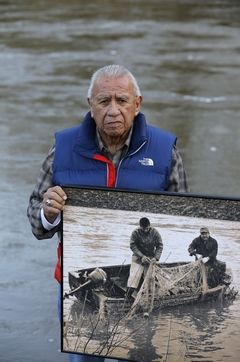

Billy Frank Jr., a Nisqually tribal elder who was arrested dozens of times while trying to assert his native fishing rights during the Fish Wars of the 1960s and ‘70s, holds a late-1960s photo of himself Monday (left) fishing with Don McCloud, near Frank’s Landing on the Nisqually River. Several state lawmakers are pushing to give people arrested during the Fish Wars a chance to expunge their convictions from the record.

By PHUONG LE, The Associated Press

SEATTLE — Decades after American Indians were arrested for exercising treaty-protected fishing rights during a nationally watched confrontation with authorities, a proposal in the state Legislature would give those who were jailed a chance to clear their convictions from the record.

Tribal members and others were roughed up, harassed and arrested while asserting their right to fish for salmon off-reservation under treaties signed with the federal government more than a century prior. The Northwest fish-ins, which were known as the “Fish Wars” and modeled after sit-ins of the civil rights movement, were part of larger demonstrations to assert American Indian rights nationwide.

The fishing acts, however, violated state regulations at the time, and prompted raids by police and state game wardens and clashes between Indian activists and police.

Demonstrations staged across the Northwest attracted national attention, and the fishing-rights cause was taken up by celebrities such as the actor Marlon Brando, who was arrested with others in 1964 for illegal fishing from an Indian canoe on the Puyallup River. Brando was later released.

“We as a state have a very dark past, and we need to own up to our mistakes,” said Rep. David Sawyer, D-Tacoma, prime sponsor of House Bill 2080. “We made a mistake, and we should allow people to live their lives without these criminal charges on their record.”

Lawmakers in the House Community Development, Housing and Tribal Affairs Committee are hearing public testimony on the bill Tuesday afternoon.

Sawyer said he’s not sure exactly how many people would be affected by the proposal. “Even if there’s a handful it’s worth doing,” he added.

Sawyer said he took up the proposal after hearing about a tribal member who couldn’t travel to Canada because of a fishing-related felony, and about another tribal grandparent who couldn’t adopt because of a similar conviction.

Under the measure, tribal members who were arrested before 1975 could apply to the sentencing court to expunge their misdemeanor, gross misdemeanor or felony convictions if they were exercising their treaty fishing rights. The court has the discretion to vacate the conviction, unless certain conditions apply, such as if the person was convicted for a violent crime or crime against a person, has new charges pending or other factors.

“It’s a start,” said Billy Frank Jr., a Nisqually tribal elder who figured prominently during the Fish Wars. He was arrested dozens of times. “I never kept count,” he said of his arrests.

Frank’s Landing, his family’s home along the Nisqually River north of Olympia, became a focal point for fish-ins. Frank and others continued to put their fishing nets in the river in defiance of state fishing regulations, even as game wardens watched on and cameras rolled. Documentary footage from that time shows game wardens pulling their boats to shore and confiscating nets.

One of the more dramatic raids of the time occurred on Sept. 9, 1970, when police used tear gas and clubs to arrest 60 protesters, including juveniles, who had set up an encampment that summer along the Puyallup River south of Seattle.

The demonstrations preceded the landmark federal court decision in 1974, when U.S. District Judge George Boldt reaffirmed tribal treaty rights to an equal share of harvestable catch of salmon and steelhead and established the state and tribes as co-managers of the resource. The U.S. Supreme Court later upheld the decision.

Hank Adams, a well-known longtime Indian activist who fought alongside Frank, said the bill doesn’t cover many convictions, which were civil contempt charges for violating an injunction brought against three tribes in a separate court case. He said he hoped those convictions could be included.

“We need to make certain those are covered,” said Adams, who was shot in the stomach while demonstrating and at one time spent 20 days in Thurston County Jail.

He also said he wanted to ensure that there was a process for convicted fishermen to clear their records posthumously, among other potential changes.

But Sid Mills, who was arrested during the Fish Wars, questioned the bill’s purpose.

“What good would it do to me who was arrested, sentenced and convicted? They’re trying to make themselves feel good,” he said.

“They call it fishing wars for a reason. We were fighting for our lives,” said Mills, who now lives in Yelm. “We were exercising our rights to survive as Indians and fish our traditional ways. And all of a sudden the state of Washington came down and (did) whatever they could short of shooting us.”