Everybody knows that coal trains are bad for our health, our economy, and our planet. So how do we stop them?

Cienna Madrid, Seattle Stranger

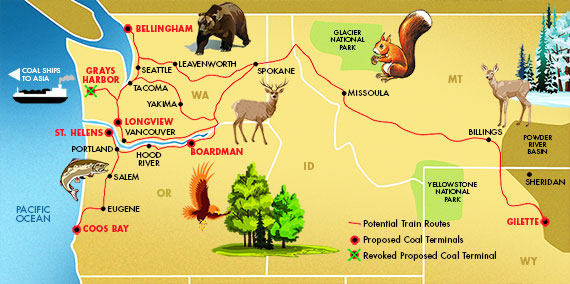

You might have heard the talk: Coal interests are pushing to make the Pacific Northwest a 24-hour conveyor belt linking coal mines in Montana and Wyoming with Asian markets clamoring for cheap, dirty power. The most urgent fight is currently taking place just north of Bellingham at Cherry Point, the site of a proposed coal-export terminal that would be the largest in North America.

Why should someone in Seattle care about a coal terminal 100 miles north of the city? Because coal combustion is the leading human-caused increase of CO2 in the atmosphere, which is largely responsible for global warming. Because shipping dirty coal to China while piously shutting down the last coal-fired power plant in Washington State (as the state is doing) would simultaneously mock and cheapen our forward-thinking, tree-humping pledge to cut greenhouse gas emissions 50 percent by 2050. And because there is not just one but five coal terminals—five!—currently proposed in the Northwest, each of which could bring 1.5-mile-long coal trains rumbling through our region daily, blocking traffic, interfering with other business at Seattle’s port, and leaving clouds of coal dust in their wake.

State and federal agencies are currently wrapping up a three-month public comment period to determine which environmental, economic, and health impacts should be studied before issuing or denying the Cherry Point terminal’s permits. Thousands of Washington residents have flocked to seven scheduled public meetings held around the state to oppose the proposal, 10,000 have submitted comments to the state Department of Ecology, 25,000 have submitted comments to the Army Corps of Engineers, and more than 40,000 people have signed a petition that’s been sent to the state’s land commissioner.

And yet, a lot of people still don’t know about the issue, don’t understand it, or don’t have an opinion. Not having an opinion on coal is like not having an opinion on climate change. And this isn’t just an environmental issue. It’s an economic issue. It’s a health issue. It’s an issue of priorities. Here’s all you need to know before the public comment period ends on January 21.

In February 2011, international shipping- terminal firm SSA Marine applied for permits to build a $500 million coal-export terminal outside Bellingham at Cherry Point, right next to a state-protected aquatic reserve and smack on top of a Native American burial ground (more on that later). The proposed Gateway Pacific Terminal would occupy nearly 1,500 acres of land, about 100 acres of which would be converted into a large open-air coal stockyard with stunning panoramic views of the Strait of Georgia and its closest neighbor, the state aquatic reserve, home to more than 300 blue heron nests and a metric fuckton of fish.

Roughly five million tons of coal is currently transported through Washington State each year to Canadian ports. This translates to about six coal trains per day (three full, three empty). The Gateway Pacific Terminal would dwarf that, shipping out 48 million tons of coal annually, circuitously hauled from sprawling strip mines in the Powder River Basin (PRB) of Montana and Wyoming. Calls to the company behind the Gateway Pacific Terminal were not returned, but the facts of its proposal are well known. Each day, 18 trains (nine full, nine empty), stretching 1.5 miles long each, would complete the journey to the Washington Coast, trundling at average speeds of 35 miles per hour through Spokane and the Columbia River Gorge, and up the coast through Longview, Tacoma, Seattle, Edmonds, Everett, Mount Vernon, and Bellingham, and back. Each train would delay traffic at railway crossings five minutes on average. (Gateway Pacific Terminal estimates delays at four minutes, while other groups have estimated seven minutes.) According to a city-commissioned traffic impact study, traffic along Seattle’s waterfront could be cumulatively delayed between one and three hours each day, significantly impacting commuter traffic, emergency vehicle response times, and freight operations at the Port of Seattle.

“It would create a wall along our waterfront,” said Mayor Mike McGinn. “The data suggests there will be more frustrations, with more bikers, drivers, and pedestrians ‘shooting the gap’ to get across—which means the potential for more accidents.”

Coal cars are typically uncovered, constantly spewing dust as they rumble down the tracks. As BNSF Railway acknowledged in a startlingly frank 2011 coal dust fact sheet, “The amount of coal dust that escapes from PRB coal trains is surprisingly large… from 500 lbs to a ton of coal can escape from a single loaded coal car.” According to BNSF, as much as 3 percent of the coal loaded into a coal car can be lost in transit: “In many areas, a thick layer of black coal dust can be observed along the railroad right of way and in between the tracks.” Aside from the health risks of inhaling coal dust, the railway explains that accumulated coal dust on tracks may cause derailments. At least 22 coal trains jumped the tracks in the United States in 2012.

Coal proponents argue that the dust can be mitigated by installing new, better coal chutes and applying “topper agents” to the coal cars. But there’s another risk when shipping PRB coal: It’s notoriously spontaneously combustible.

“Operators familiar with the unique requirements of burning PRB coal will tell you that it’s not a case of ‘if’ you will have a PRB coal fire, it’s ‘when,'” notes a 2003 article published by the coal industry group Utility FPE Group Inc. The article continues, “Although prevention is cheaper than repairing fire and explosion damage, its costs always seem difficult to justify.”

“Spontaneous combustion of coal is a well-known phenomenon, especially with PRB coal,” states an industry research paper called “PRB Coal Degradation—Causes and Cures.” “This high-moisture, highly volatile sub-bituminous coal will not only smolder and catch fire while in storage piles at power plants and coal terminals, but has been known to be delivered to a power plant with the rail car or barge partially on fire.”

It’s probably inaccurate to picture mile-long flaming coal train cars inching across the state, says the Northwest environmental research organization Sightline Institute: “The threat is likely to be more insidious—slowly smoldering coal that is perhaps emitting noxious gases into neighboring communities. Yet the severity and toxicity of these gases are largely unknown.”

Some of the worst health effects would be felt in the communities surrounding Cherry Point. The terminal’s port would be large enough to berth three cargo ships at once. Coal would be conveyed from the 100-acre coal stockyard along a 1,250-foot trestle linking ships to shore. Heavy machinery would troll the coal piles, continuously rotating them to discourage combustion, kicking up even more coal dust with each turn.

Common sense and science tell us that working with coal will shorten your life span. The US Department of Labor links coal dust to pneumoconiosis, regular bronchitis, chronic bronchitis, emphysema, “rapidly developing lung damage,” and premature death in exposed workers. It’s also been known to cause lymphoma and adrenal tumors in test animals.

But alarmingly, very little research has been done on the nonoccupational environmental health effects of coal dust on people. Here’s what we do know: Coal dust contains concentrations of heavy metals including arsenic, lead, mercury, and cadmium. Furthermore, rainwater runoff from coal stockpiles can leach into the soil and contaminate groundwater that people and animals drink.

“We’re concerned about increased air pollution and the effects it can have on patients,” testified Dr. Melissa Weakland at a public hearing on the Gateway Pacific Terminal held in Seattle’s convention center on December 13. Speaking on behalf of the Washington Academy of Family Physicians, Dr. Weakland also echoed concerns about delays in emergency response time, heavy metal poisoning, pulmonary problems, and cancer. “Many health specifics in this proposal are left unanswered,” Dr. Weakland said.

The Seattle public hearing was the last of seven held around the state. The meetings were crowded, tense, and predominantly packed with protesters—including heavy hitters like Seattle mayor Mike McGinn, a handful of Tacoma and Seattle city council members, King County executive Dow Constantine, and state representatives Joe Fitzgibbon (D-34) and Reuven Carlyle (D-36). But the most moving testimony came from a 12-year-old.

“I appreciate the natural wonders of this state,” testified Rachel Howell of Queen Anne to a packed convention center ballroom. “I like salmon. I like oysters. Global warming is threatening salmon and oysters. I like to ski at Snoqualmie Pass. In my lifetime, I will not be able to ski at Snoqualmie Pass because of global warming. This is the future you’re creating for us, and this is not the future we want. It’s pretty simple, even I understand: If you make coal more available, more people will use it.”

We can’t fight global warming by exporting our carbon: It’s an issue that’s simple enough for a 12-year-old to understand. The rest of us? That remains to be seen.

Lobbying in support of the coal terminal is the Alliance for Northwest Jobs & Exports, a pro-coal group formed last July to counter all of the bad press about heron habitat, heart disease, and spontaneous combustion. The Alliance is composed of 54 organizations representing almost 400,000 employees in Washington, Oregon, and “around the country,” according to spokeswoman Lauri Hennessey. The group has downplayed health and statewide environmental concerns.

“It’s impossible to consider the cumulative impact of coal trains; it’s purely speculative,” said labor union representative and Alliance member Herb Krohn at the December 13 public meeting. “Coal is a naturally occurring mineral, the coal dust discharged is minimal, and this argument that it impacts health is specious at best.”

Hennessey would not address specific environmental or health risks raised by citizens directly, saying only: “If people have concerns, they should write those concerns in.” If the government’s environmental impact study sees fit to address those concerns, “we’ll do whatever mitigation is necessary,” she adds.

Meanwhile, the group is purported to have spent $1 million in television ads in the Northwest to transform coal trains into huggable, huffing economic engines (Hennessey would neither confirm nor deny the amount spent, only calling it “sizable”). They claim the terminal will bring in $25 million in new tax revenue once built, as well as 4,400 new jobs, most of which would be two-year construction jobs. Gateway Pacific Terminal has promised the project would create 294 to 430 permanent local jobs.

But critics say that the job numbers don’t take into account the many careers the Cherry Point coal terminal would destroy.

“Anyone who claims that this massive coal project is about jobs had better learn to subtract,” testified Pete Knutson, a 40-year career fisherman, owner of the Loki Fish Company based out of Ballard, and a commissioner on the Puget Sound Salmon Commission (WSDA). “We have 15,000 fishery jobs in Puget Sound; now our marine livelihoods are at stake. A job is not necessarily a livelihood. We’re weighing jobs based on the one-time exploitation of a fossil fuel versus livelihoods based on a sustainable resource. We have a moral obligation to reject this proposal.”

Cargo operations at the Port of Seattle would also be threatened, both from the increased traffic through Sodo and from competition for scarce rail capacity. Washington’s freight rail system is already pushing its limits—18 additional coal trains a day would drive up prices for other shippers.

Opposition to the terminals is mounting: More than three dozen cities, counties, and ports, close to 600 health professionals, 220 faith leaders, and more than 450 local businesses have either voiced concern or come out against coal export off the West Coast. Many tribal governments, including the Lummi Nation, have also organized to oppose coal export after terminal contractors were issued a cease-and-desist order in June 2011 for bulldozing sacred Lummi burial grounds without permits.

“Cherry Point is flagged as a cemetery. That’s not oral history, that’s fact,” Lummi Nation spokesman Jay Julius says. “That is our Jerusalem. That is our holy ground.”

Three dozen municipalities, including the Seattle City Council, have passed symbolic resolutions in outright opposition to the proposals or at the very least demanding that state and federal agencies execute a full, comprehensive environmental impact study (EIS) on the cumulative impacts of coal trains and exports.

“I’m here speaking on behalf of dozens and dozens of state officials who’ve all called for a comprehensive, cumulative impact analysis to this proposal,” testified Representative Carlyle at the December 13 Seattle hearing. “That means a thorough, data driven analysis of the economic externalities of this proposal—the transportation, the health, the safety impacts that our communities will face. We’re asking you to acknowledge that most communities don’t have the resources to do their own economic analysis. It’s critical that this EIS be thorough, be data driven, and recognize the profound implications on our quality of life.”

Interstate commerce laws prevent local authorities from outright blocking coal trains from passing through their jurisdictions, so the only way to stop the trains is to stop the terminals. But the path to blocking the Gateway Pacific Terminal and other terminal proposals in Longview, Washington, and Boardman, St. Helens, and Coos Bay, Oregon, is murky. Each terminal is being pushed by separate coal interests and each faces its own timeline and permitting process for approval. Opponents fear that if one proposal goes through, the amount of coal they plan on shipping will increase exponentially to meet market demands.

“The coal industry has already lied about the amount of coal they were planning on shipping out of Longview,” says Krista Collard, a spokeswoman for the Sierra Club. “When that was discovered, they had to pull permit applications and refile.” A spokesperson for Millennium Bulk Terminals, the organization behind the Longview proposal, didn’t respond to a request for comment.

In order to proceed with the coal terminals, companies must first secure development permits from local county councils, aquatic lease permits from public lands commissioner Peter Goldmark, and approval for the projects from the state Department of Ecology and federal Army Corps of Engineers. The biggest challenge, opponents say, is to orchestrate killing all five of the proposals at once—not just the terminal at Cherry Point.

“It’s not about one entity, it’s about the big picture,” explains Kimberly Larson, a spokeswoman for Climate Solutions, which is working with the Sierra Club and other environmental groups to organize Northwest opposition efforts in both Oregon and Washington. “They’re all in play at the same time, and that’s why it’s important to show the collective resistance across the region. If one goes through, it will affect all of us.” For instance, coal trains headed to Oregon would still trundle through Spokane and the Columbia River Gorge, impacting communities along the way and clogging Washington’s freight rail system. You can help Climate Solutions and the Sierra Club by writing letters opposing the terminals to Commissioner Goldmark (cpl@dnr.wa.gov), the US Army Corps of Engineers and the Washington State Department of Ecology (eisgatewaypacificwa.gov/get-involved/comment), as well as to your state, county, and city representatives.

Protesters already helped kill one coal terminal last summer, slated for Grays Harbor. “After hearing from the community, the terminal said that they wanted to ship friendlier, healthier items than coal out there,” Collard explains.

That’s the sort of victory coal train opponents hope to achieve throughout the Northwest. “We share a vision for a better future,” testified King County executive Dow Constantine at Seattle’s public hearing on the Cherry Point terminal. “Our vision doesn’t include 18 trains a day pulling those coal cars through the heart of Washington. This isn’t just a regional issue; it’s a global issue and a generational issue. In Washington, we have done away with coal-fired plants, but shipping overseas will overwhelm the gains we’ve made here at home.”

A 12-year-old couldn’t have said it any better.