Gale Courey Toensing, Indian Country Today Media Network, March 27, 2013

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, the legislation that dramatically changed the economic landscape for tribal nations with casinos. In recognition of that momentous event, Indian Country Today Media Network decided to take a look at some of the early heroes of Indian gaming—the tribes and individuals who advanced it both before and after the passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act.

TABLE STAKES

The precursor to IGRA was the 1987 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in California v. Cabazon Band of Indians, which upheld the right of sovereign Indian nations to conduct gaming on Indian lands free of state control when similar gaming is permitted by the state elsewhere. While Cabazon is often cited as the legal foundation for Indian gaming, a Supreme Court ruling more than a decade earlier paved the way for Cabazon: Bryan v. Itasca County. Russell and Helen Bryan, the Chippewa couple who brought the case forward, deserve a top spot on the list of early Indian gaming heroes, even though they had nothing to do with gaming.

In June 1972, the Bryans received a personal property tax bill for $29.85 from Itasca County in Minnesota, an assessment on their trailer home on the Leech Lake Indian Reservation. They took it to the local Legal Aid Society office, and attorneys there brought a lawsuit to challenge the tax bill in state court. The assessment, which kept going up over time, was challenged all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, and in June 1976, the high court ruled that states do not have authority to tax Indians on Indian reservations or to regulate Indian activities on reservations.

“Bryan thus was the bedrock upon which the Indian gaming industry began,” Kevin K. Washburn wrote in a Minnesota Law Review article entitled: “The Legacy of Bryan v. Itasca County: How an Erroneous copy47 Tax Notice Helped Bring Tribes $200 Billion in Indian Gaming Revenue”. Washburn, who was Oneida Nation Visiting Associate Professor of Law at Harvard Law School when his article was published in 2007, is currently the Interior Department’s Assistant Secretary—Indian Affairs. “If economic impact is a useful measure of importance, Bryan may be the most important victory for American Indian tribes in the U.S. Supreme Court in the latter half of the 20th century. Indian gaming is simply the most successful economic venture ever to occur consistently across a wide range of American Indian reservations,” Washburn wrote. If there’s any doubt about the importance of Bryan, he added, “consider that on the basis of the Bryan precedent, the Indian gaming industry was generating between copy00 million and $500 million in annual revenue before Cabazon was decided.”

And, indeed, all across the U.S., Indian country was bustling with gaming activities during the 1970s and 1980s.

THE BIRTH OF RED CAPITALISM

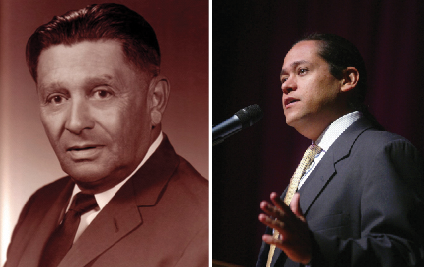

One of Turtle Island’s greatest advocates for Indian sovereignty and self-determination was the late, iconic Mescalero Apache leader Wendell A. Chino. Born in 1923, Chino was elected chairman of the Mescalero Apache’s tribal governing committee at the age of 28 and was reelected every two years until 1965 when he was named the first president of the Mescalero Apache Tribe, serving in that capacity for 16 consecutive terms.

Chino spearheaded the tribe’s shift to controlling its own natural resources, and by the same philosophy of “red capitalism,” in 1975 the Mescalero Apache Nation built the Ski Apache Ski Resort and the Inn of the Mountain Gods resort in the Sierra Blanca Peak, including the first tribal-owned golf course in the United States. At the Mescalero resort property, Chino was also instrumental in establishing one of the earliest Indian casinos (now called the Inn of the Mountain Gods Resort and Casino) by asserting that the state of New Mexico could not outlaw gaming on sovereign tribal land.

Chino led his Nation until his death in 1998 at the age of 74. “In the scheme of the 20th century, it has been said that Wendell Chino was a Martin Luther King or a Malcolm X of Indian country. He was truly a modern warrior,” said Roy Bernal, then chairman of the All Indian Pueblo Council and a member of the Taos Pueblo, in Chino’s obituary in the The New York Times.

![From left: Hayward, Tommie and Halbritter (Courtesy Seminole Tribune/Seminole Tribe of Florida [Tommie]; courtesy Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation [Hayward]; Onieda Indian Nation [Halbritter])](http://ictmncdn1.tgpstage1.com/sites/default/files/default/files/uploads/screen_shot_2013-03-26_at_4.03.54_pm.png)

Fifteen years ago, the National Indian Gaming Association (NIGA) established the Wendell Chino Humanitarian Award in his name to recognize tribal leaders whose actions have improved the lives of citizens in Indian country. For the first time, in 20 the award was presented to an entire tribe, the Quapaw Tribe of Oklahoma, whose altruistic and humanitarian actions helped tornado victims and their devastated community of Joplin, Missouri.

The winner of this year’s award will be honored on March 26 at the Wendell Chino Humanitarian Award Banquet during NIGA’s Indian Gaming 2013 Tradeshow and Convention in Phoenix.

On the East Coast, the Oneida Indian Nation, the Seminole Indians of Florida and the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation were among the earliest to develop Indian gaming.

FROM THE ASHES

Oneida’s gaming enterprise emerged from a tragedy. In June 1976, the aunt and uncle of Ray Halbritter, Oneida Nation Representative and Chief Executive Officer of Nation Enterprises, parent company of Indian Country Today Media Network, burned to death after their trailer caught fire. “The city of Oneida, which is named after us, refused to send the fire department,” Halbritter says. “It was a very tragic time for us. It was horrible.”

Tensions both on and off the reservation were running high because the nation had filed a lawsuit to restore its land rights, which was opposed by many in the surrounding communities. The reservation by that time had been reduced to 32 acres divided into 36 trailer lots, with a mud road down the center and no services. After that tragic fire, the nation’s leaders knew they needed to provide fire protection for the people, but there was no money, Halbritter recalls. They decided to follow the lead of the small fire departments and charities in the surrounding communities that held bingo and “Las Vegas” gambling nights as fund-raisers.

By October of that year, the Oneidas’ bingo operation was up and running. In an effort to develop a better relationship with the city of Oneida, the nation planned a bingo night fund-raiser for the city police department’s benevolent society. The nation informed the state of its plans and invited members of the police department to the event. “A certain number of police came representing the department, but we didn’t anticipate they would use the opportunity to arrest us for operating bingo without a license,” Halbritter recalls.

The nation didn’t have money to wage a legal battle against the state, so their high-stakes bingo operation was shut down. The Oneidas then opened a high-stakes bingo operation in 1985 after the Seminoles in Florida had fought—and won—some of the most important legal battles for Indian gaming. “After they went through all the legal battles, I went down there to visit and they had a flier that told the story of Seminole bingo and they mentioned the Oneida Nation of New York; they talked about the bingo that we had stared years earlier,” Halbritter says.

By 1993, the Oneida Nation, under Halbritter’s leadership, transformed its high-stakes bingo operation into the hugely successful Turning Stone Resort Casino, a world-class golf, gaming, entertainment and hotel resort destination.

SOVEREIGNTY IN THE SUNSHINE STATE

The Seminoles, under the leadership of Howard Tommie, had opened a high-stakes bingo hall on their reservation on December 14, 1979. It was the first casino on Indian land in the country and Broward County Sheriff Robert Butterworth threatened to shut it down and arrest the Seminoles for allegedly violating a Florida gaming statute the minute it opened. The tribe sued the county in Seminole v. Butterworth and won in both federal district court and in the appeals court, which upheld the lower court ruling that Indian tribes have sovereignty rights that are protected by the federal government from interference by state government. The ruling affirmed the Seminoles’ sovereign right to conduct high-stakes bingo on its land and established the tribe’s leadership in Class II gaming.

THE CONNECTICUT MIRACLE

Meanwhile, in Connecticut Pequot leader Skip Hayward was engaged in a three-pronged battle: (1) to save the Pequot reservation from a state takeover after his grandmother Elizabeth George died in 1973, leaving the 200-acre reservation without any residents; (2) to re-establish the fragmented Pequot people as a tribal community and (3) to gain federal acknowledgment. Working with attorneys in a Legal Aid office in 1974 and following a model set by the Penobscot and Passamaquoddy tribes in Maine, Hayward initiated a land claim lawsuit based on the 1790 Indian Nonintercourse Act and drafted a settlement agreement. The land claim raised a storm of opposition in the community and throughout the state, and was challenged in federal court. In 1983, the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation received from Congress 2,000 acres of land, federal acknowledgement, and $300,000 to invest in tribal economic development. Thus began the path that led to the creation of Foxwoods Resort Casino, the largest gaming facility in the country, and to an authentic and astonishing rags-to-riches story for the Pequot people.

“Clearly, we would not be here today without the remarkable dedication and commitment of our early leadership and that goes back to Skip Hayward,” Mashantucket Pequot Chairman Rodney A. Butler says. “His willingness to stand up and fight for Indian rights in the 1970s and again in the 1980s

![Clockwise, top left: Wendell Chino, Jana McKeag, Leonard Prescott, Marge Anderson (Richard Pipes/Albuquerque Journal [Chino]; courtesy Leonard Prescott](http://ictmncdn1.tgpstage1.com/sites/default/files/default/files/uploads/screen_shot_2013-03-26_at_4.04.07_pm.png)

on Indian gaming can’t be underscored enough. Clearly we wouldn’t be here without his persistence and efforts.”

Hayward started a very successful high-stakes bingo operation in 1986. After the Cabazon ruling in 1987 and the passage of IGRA in 1988, the nation began its pursuit of a casino. By 1993, the bingo operation had evolved into the full-fledged Foxwoods Resort Casino. Hayward had envisioned Foxwoods as the first world-class, family-oriented destination resort casino. “That was a tremendous credit to him and where he wanted it to grow,” Butler says.

Foxwoods’s spectacular success has stood as an inspirational story for all of Indian country, he adds. “Here’s this small tribe from Connecticut now owning one of the largest casinos in the world—we can all do that, right? Well, we can’t all do that, but just the inspiration and hope that it provided, I think, was a big influence on Indian gaming.”

MYSTIC LAKE

The Shakopee Mdwakanton Sioux (Dakota) Community in Minnesota was treading a similar path to Indian gaming success in the early 1980s. The poverty-stricken tribe opened a high-stakes bingo hall in 1982, which laid the groundwork for the development of Mystic Lake Casino a decade later. Leonard Prescott, a founding member of the National Indian Gaming Association in 1985, became the Shakopee chairman in 1987. “I built Mystic Lake Casino in 1991, 1992,” Prescott says. Under his leadership the Shakopee and other Minnesota tribes negotiated the first tribal state gaming compacts in the country in 1989. “The compacts are perpetual,” he says. “We have no time limits. We have no jackpot limits. We pay copy0,000 per tribal government which means today we pay copy50,000 to the state of Minnesota for a $2.5 billion business.”

The Mystic Lake Casino Hotel is one of the most successful in the country, providing the less than 400 citizens of the nation with more than copy million annually in payments. The nation also has a philanthropic program that has distributed hundreds of millions of dollars to local governments, organizations and people in Indian country. Last year, Shakopee donated $29 million.

Prescott says he is astounded at the tribe’s transformation. “When we first developed our bingo hall, we had a dirt road, we were making tracks to our building that sold welfare products, we had no sewer and water. So coming from there to where we are today is miraculous.”

WEST COAST FAST-TRACK

California developed the largest number of Indian gaming facilities in the shortest amount of time in the 1980s and 1990s, and even now—with 62 gaming tribes—it has the highest number of gaming tribes in the country, according to Casino City’s Indian Gaming Industry Report for 2013. The Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians opened its casino in 1995, the last tribe to do in the state during that early era, said Pechanga Chairman Mark Macarro. Numerous California tribes had successful bingo operations in the 1980s—the San Manuel, Morongo, Cabazon, Barona, and Viejas, Sycuan and Yocha Dehe. “These were the first and therefore the trailblazers,” Macarro says.

Several California tribal gaming facilities were shut down in the 1980s by sheriffs eager to prove tribal gaming was illegal under state laws. Those raids led directly to the watershed ruling in Cabazon, “which then rather quickly was contained and abridged in October of 1988 by the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act,” Macarro says.

But state opposition didn’t stop even after Cabazon and IGRA. Then-governor Pete Wilson disliked gaming and refused to negotiate with the tribes, despite IGRA’s mandate that he do so. Wilson complained about tribal gaming to anyone who’d listen—federal and state officials, Congress, U.S, attorneys, law enforcement, Macarro recalls. Finally, in March 1997, U.S. Attorney Nora M. Manella took action. “Each tribal chair (myself included) was issued a summons to appear in Los Angeles Federal District Court. Our machines had been legally seized, i.e. they were arrested—it’s called in rem seizure.”

The tribal leaders didn’t go to jail, and they called for a huge demonstration. Around 5,000 to 7,000 employees and supporters rallied and shut down the streets of downtown Los Angeles, Macarro says. “The point was: Shut us down? Do so and lose a huge economic engine and these thousands of people go unemployed. The high-point of this rally was when all the tribal chairs stood literally in unity on the top step of the courthouse—summons in hand—and spoke to the crowd. It galvanized us as a group and forged a strong bond which became the keystone for the first statewide ballot proposition battle—Prop 5—in 1988. This was the next major evolution for tribal cohesion and became a watershed period.” Macarro says. Prop 5 passed with 62 percent of the vote and established tribal-state compacts that allowed, among other things, slot machines in tribal casinos.

DOUBLING DOWN

This has been only a partial look at the early Indian gaming “heroes”—it would be impossible to acknowledge the contributions of everyone who worked to make Indian gaming a reality. But no list of Indian gaming trailblazers would be complete without mention of two great women of gaming: Marge Anderson, of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe in Minnesota, was the driving force behind the opening of Grand Casino Mille Lacs and Grand Casino Hinckley within four years of the passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988; Jana McKeag, of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, was one of the commissioners on the newly created National Indian Gaming Commission in 1991 and began the commission’s first task—writing the regulations that govern Indian gaming.

In the years since the passage of IGRA, Indian gaming has grown to a $27 billion-plus a year industry, giving tribal governments the means to build their nations and provide services for their citizens. It has also infused the U.S. economy with hundreds of billions of dollars and almost 700,000 jobs. While there are potential threats to Indian gaming in the long-term, the industry is likely to continue its success into the mid-term future, says economist Alan Meister, author of Casino City’s Indian Gaming Industry Report for 2013. “The economy will continue to improve over time, bringing back disposable income, consumer confidence and spending on casino gambling.” So, in the words of former Shakopee chairman Leonard Prescott, it is likely the country will be able to enjoy the miraculous phenomenon of Indian gaming for the foreseeable future.