By Kyle Taylor Lucas, Tulalip tribal member, guest reporter

Joan Staples-Baum, Director, Tahoma Indian Center

She is nearly seventy, but you wound not guess she is a day over fifty. There’s a twinkle in her eye, but immediately striking is a sense of inner strength, wisdom, and dignity. Her eyes say that she has seen much. No doubt, great inner strength was pivotal to her daily work with Native America’s rejected and forgotten, many of whom live under bridges and on the streets of Tacoma. She is Joan Staples-Baum, White Earth Chippewa from Minnesota, and she has been the program manager at the Tahoma Indian Center for nearly 22 years.

At the end of this year, Staples-Baum will leave the center that she and two other American Indian women, Betty Sampson, Swinomish and Jeanette DeCoteau, Turtle Mountain Chippewa, founded in October 1991. Sampson, who worked daily at the center, sadly since deceased. DeCoteau is a Physician’s Assistant at Muckleshoot Tribe.

“To me the key to survival as an Indian is to know who you are,” said Staples-Baum. Over the past 22 years, she has dedicated her life to ensuring that urban Indians in Tacoma get that chance.

In January, Staples-Baum will journey across country to join the love of her life, Gilbert Moran, Turtle Mountain Chippewa, in Belcourt North Dakota where, among pursuing interests long put on hold, she will help him write a book documenting his language as one of its last speakers.

An artist, she’ll pursue arts and crafts, further research family ancestry, and infuse her life with more spiritual direction as well.

Joan Staples-Baum was born in 1942, the middle child of ten. Her parents moved off the reservation to provide educational opportunities for their children. She noted that it is hard for those who have left the reservation, often through no fault of their own. When they attempt to return home, they are not accepted.

Also of Finnish descent, in 1988 she traveled with her mother to Finland where she met her mother’s first cousins. “Finland is so Indian it’s unbelievable! Oh my God, I got a double whammy being Finnish and Indian.” She described a community set up like longhouses where adults lived in the big house, kids in small houses, with a full range of community services in the middle.

Staples-Baum completed her undergraduate work at Seattle Pacific University and earned her MSW at Seattle University in 1997. She is the mother of two and the proud grandmother of two grandchildren, ages 8 and 12.

Tahoma Indian Center

According to its mission, the Tahoma Indian Center was “established to help restore and sustain the dignity of Urban Native American Indians. We believe in living out a ministry of presence by offering a safe place where hopes can be revived, hearts healed, and lives can begin anew. We are a drop-in resource center designed to nurture and build up Native Peoples through service and advocacy.”

It is a long narrow building with a bright blue front at 1556 Market Street in Tacoma and is open Monday through Friday from 9:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. Those utilizing the center and its services consider it a blessing. Upon entrance, one feels immediately welcomed. Tables with chairs line both sides of the long room, a long series of comfortable benches line the center of the room. A computer center is available where Indians can access their email, search and apply for jobs, or seek information. There is access to a phone, a physical address for mail, and laundry services. The coffee is always ready and a full meal is served once daily.

The center provides referrals to needed social services such as housing, food, clothing, employment and training, legal services, education, as well as referrals to culturally specific services such as tribal registration, pow-wows, counseling, recovery, and healing

The center operates under the umbrella of Catholic Community Services and receives the bulk of its funding from grants and the support of funders such as the Tulalip Tribes, Muckleshoot Tribe, Puyallup Tribe, Snoqualmie Tribe, and the United Way of Pierce County. Last year, the center served 1,133 urban Indians.

Staples-Baum emphasized, “We’ve intentionally not sought local government funding because we would have to open the doors to everyone and we feel it’s important to maintain the center for Natives. I’ve seen what happens when you accept that funding, the Natives get lost in the mix.” Essentially, the Native people and their unique needs are over-shadowed.

Prior to founding the Indian center, Staples-Baum worked at another local support center and noticed that the Indians came in, quietly got their plates, and went to the back. Shortly thereafter, she, Sampson, and DeCoteau, hatched the idea to create a center that would focus on the unique cultural and identity needs of urban Native peoples.

Pointing to a beautiful portrait of Kenny Moses, a traditional healer of the Tulalip Tribes, she happily recalled his special blessing of the center at its original location on Yakima Street in 1991.

The center has a board of 12 members, all Native except for one representative of the Catholic Community Service. Some are center users. Tahoma Indian Center Board Chair, Peter Hayes (Choctaw), and his wife and family bring the Native community together every year to prepare and serve Thanksgiving dinner.

On a more sober note, more than a third of those served by the center are homeless Indians. They sleep at homeless shelters, under bridges, or in their cars. The average age is 30 to 45, some veterans, a few over 50. About a third of those served are women whose needs are unique because they are especially vulnerable living on the streets.

“We welcome all Indians to the center and we don’t judge. We try to help them find their way. According to the 2010 census, the majority of Natives live in the city today, and most of them for reasons not of their own doing. We’re scattered around. We don’t have a housing section. The center helps us find each other,” said Staples-Baum.

The center has been a cultural center, too, a place for Indians to practice beading, to weave, to drum, to dance. They have held classes in drum making and in beadwork and weaving, and have encouraged center clients to avail themselves of Native art classes through The Evergreen State College longhouse and with Native teachers in classes at the center.

When asked whether she has been involved in political advocacy for urban Indians, Staples-Baum said, “I have no right to intervene with any of the tribes, politically. My role is to ensure a neutral line. We have been grateful for the support of the tribes.” She once worked with a few others in securing passage of a resolution by Affiliated Tribes of Northwest Indians to support urban Indians, but said that nothing more came of it.

Memorial Wall

A grim reminder of the tragic lives of a majority of those served by the center is the center’s memorial wall. Most of those remembered passed from suicide, murder, drugs, alcohol, or cancer. Tragically, “There’s probably not one natural death on it,” said Staples-Baum who pointed to photos, “See that young woman in the hat, she’s Tulalip, and she was strangled to death; that young man was murdered; she died of AIDs, he was killed by police; he committed suicide; he died of drugs.”

Despite the legacy of desperate lives, likely otherwise forgotten, on the memorial wall, the center has and continues to fulfill the wide-spectrum of the human experience, including celebrations of life. “We’ve had naming ceremonies, baptisms, weddings, Shaker Church services, memorial services, and funerals.”

Tyrone Patkoski – Tulalip “Outside Artist”

Against the stark realities and lives of those served by the center, when asked what has kept her going all these years, Staples-Baum said, “It’s people like Tyrone Patkoski.”

Tyrone Patkoski, an enrolled Tulalip tribal member, has lived on the margins of society for most of his life and on the streets for more than three decades. His last job was in 1976 when he cleaned movie theaters. Since then, he has survived by selling metals, which he said, “kept gas in the car and the insurance paid.” Staples-Baum said, “Tyrone was one of the first environmentalists, believing in re-use.” Tyrone often incorporates found objects into his art.

Patkoski said he first became homeless in the early seventies, “Starting about 1971, I was wandering around, staying in my panel truck. Some people let me park at their house. Wasn’t no fun driving around trying to find a place to stay. After that, I sometimes lived under the bridge, or slept in my car when I had one.” He was especially happy about the years that the Puyallup Tribe allowed him to stay at the river.

Despite a difficult adulthood marked by homelessness, periods of mental illness and depression, Tyrone shared fond memories of his youth and times spent with extended family in cascara bark gathering, berry picking, and trout fishing. He happily recalled how he “wandered around the mountains with family and we’d get together for picnics.” He shared black and white photos of his lovely young mother and father, saying that his father was in the army and the navy. His tone was disapproving as he recalled that his dad used to shoot bottles off the top of his mother’s head. He was clearly proud of his uncle Kenny Moses and marveled that his uncle Amos Moses was hit twice by lightening.

Staples-Baum said that she met Tyrone when his sister brought him into the center 20 years ago. He worried about losing his art to street thugs, so she offered to store it at the center. While she had marveled at his artwork, Patkoski’s big break came when she introduced him to former News Tribune photographer Casey Madison. Madison admired his work and encouraged Staples-Baum to frame it, so she secured $2,000 in funding from an anonymous donor. Tacoma Art Supply framer Glenn Leonard loved Tyrone’s work and helped organize the first exhibition and public recognition of his art in May 2010. Tyrone and his show were also featured on King5 television. Total sales amounted to a few thousand dollars, which has helped to support him and to buy canvasses, brushes, and paint. Tyrone Patkoski’s work can been seen at www.TyronePatkoski.com.

In a “Weekly Volcano” review of Tyrone’s art, Alec Clayton said, “An unheralded and untrained artist with innate talent, guts and sincerity is discovered. There is nothing in these densely packed images that does not refer to something in his life experience, his demons, or his hopes.”

Asked what inspires him, Tyrone mumbled, “I don’t think about what I’ll paint. I just let the paint decide.” Asked when he creates, he said, “I like to work at night when I have materials, but I need linseed oil, canvasses, and brushes – which are expensive.”

At the mention of his sister, Helen, Tyrone was cheered, but suddenly blurted, “Helen died from alcohol, she had a rough life. Her boyfriend got her drinking Thunderbird and eventually she had an aneurism and lost half her memory. Then she died.” He choked, “Rainy days are hard. When it gets rainy, I always think about Helen,” a tear rolled down his cheek. Wiping it away with his sleeve, he was unable to talk. One is struck by his vulnerability. He seemed appreciative of a stranger’s condolence and consolation, though it was clear that such human touch was unfamiliar. Even upon meeting and extending a handshake, he reacted in surprise as though such a gesture is rare.

Tyrone is a big guy, at least 6’ tall with broad shoulders. Staples-Baum calls him a “gentle giant,” and later remarked, “I’m happy and surprised that he opened up and talked with you, he rarely speaks to anyone, so this was unusual and special.” Perhaps it helped to be interviewed by another Tulalip who happens to be a freelance journalist, but also by someone who treated him as an equal.

Since about the age of 20, he says his medium has mostly been “oil paints on canvass and acrylics on the bugs with some ink pens on paper,” but many of his early works were ink drawings on the backs of file folders and boxes.

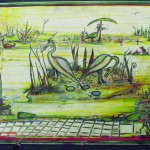

After the center closed, we three stayed late for the interview. In the sudden quiet, Staples-Baum brought out of storage a huge 4-foot folio of Tyrone’s work. She began to lay the very unique and colorful pieces out, all the while gently asking Tyrone about them. Before long, he was quietly chuckling and offering brief, shy, comments about the various aspects, influences–Van Gogh and Picasso, and meanings of his truly remarkable drawings and paintings.

Shy and humble, he seems almost childlike, yet his art often conveys deep thought, sometimes dark and disturbing reflections on drugs, needles, 8-balls, alcohol, gambling, and the painful and destructive human experiences he has witnessed first-hand on the streets; then, alternately humorous commentary of current affairs and the mundane.

Tyrone is an environmentalist who paints ducks stuck in an oil spill, a moralist who draws monkeys being shot into space in rockets, and a humanist who decries Satan stealing humans with needles and 8-balls depicted in many of his drawings and paintings. Then, there are his acrylic 3-dimensional bug pieces that depict the human existence from the sublime to the ridiculous.

The fortunate viewer is instantly struck by the abstract and intricate designs with layered meanings infused in each Patkoski art piece, whether his drawings, oil paintings, watercolors, or 3-dimensional acrylic pieces. Yet, Tyrone has quickly moved on to the 4-foot portfolio where he delights in re-discovering and sharing his past works, some dating to the early seventies. If Tyrone is quietly pointing out the next piece, one dare not be detained by the last mesmerizing piece.

After living on the street, under bridges, and in his car or panel van for nearly thirty years, Tyrone Patkoski finally has a home of his own. A kindly man who became his friend had allowed him to stay on his property. “I spent about ten years sitting in the car outside Butch’s house with ink pens and paper. He brought me there to be his security guard.” When he passed away, he left his house to Tyrone. Staples-Baum contacted Tulalip Tribes when he was, shortly thereafter, about to lose the home due to back-taxes. She said, “Tulalip Tribes stepped in to help Tyrone and keep his home from foreclosure.”

Asked what he liked best about having a home, Tyrone’s stark and simple reply is, “It’s really nice when it’s cold and rainy.”

Hopes for the Center’s Future

As Tahoma Indian Center founder, Joan Staples-Baum leaves, she shared her thoughts on her legacy and hopes for the center’s future. Her parting thoughts are characteristically in keeping with the pragmatic and humble approach she has taken to managing the center for 22 years. “I hope there will not only be a safe place for urban Indians to hang out during the day, to get something to eat, and to have a sense of community, but I hope the center will provide a space where people feel safe to be who they are, feel respected, and to be inspired to make changes themselves.”