By Sandi Doughton, The Seattle Times

SEATTLE — Nearly two decades after the ancient skeleton called Kennewick Man was discovered on the banks of the Columbia River, the mystery of his origins appears to be nearing resolution.

SEATTLE — Nearly two decades after the ancient skeleton called Kennewick Man was discovered on the banks of the Columbia River, the mystery of his origins appears to be nearing resolution.

Genetic analysis is still under way in Denmark, but documents obtained through the federal Freedom of Information Act say preliminary results point to a Native American heritage.

The researchers performing the DNA analysis “feel that Kennewick has normal, standard Native American genetics,” according to a 2013 email to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which is responsible for the care and management of the bones. “At present there is no indication he has a different origin than North American Native American.”

If that conclusion holds up, it would be a dramatic end to a debate that polarized the field of anthropology and set off a legal battle between scientists who sought to study the 9,500-year-old skeleton and Northwest tribes that sought to rebury it as an honored ancestor.

In response to The Seattle Times’ records request, geochemist Thomas Stafford Jr., who is involved in the DNA analysis, cautioned that the early conclusions could “change to some degree” with more detailed analysis. The results of those studies are expected to be published soon in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. Stafford and Danish geneticist Eske Willerslev, who is leading the project at the University of Copenhagen, declined to discuss the work until then.

But other experts said deeper genetic sequencing is unlikely to overturn the basic determination that Kennewick Man’s closest relatives are Native Americans.

The result comes as no surprise to scientists who study the genetics of ancient people, said Brian Kemp, a molecular anthropologist at Washington State University. DNA has been recovered from only a handful of so-called Paleoamericans — those whose remains are older than 9,000 years — but almost all of them have shown strong genetic ties with modern Native Americans, he pointed out.

“This should settle the debate about Kennewick,” Kemp said.

Establishing a Native American pedigree for Kennewick Man would also add to growing evidence that ancestors of the New World’s indigenous people originated in Siberia and migrated across a land mass that spanned the Bering Strait during the last ice age. And it would undermine alternative theories that some early migrants arrived from Southeast Asia or even Europe.

It’s not clear, though, whether the upcoming study will provide tribes the legal ammunition they need to reclaim what they call “The Ancient One.”

Controversy flared over the skeleton almost from the moment in 1996 when two students stumbled across human bones near the Southeastern Washington town of Kennewick.

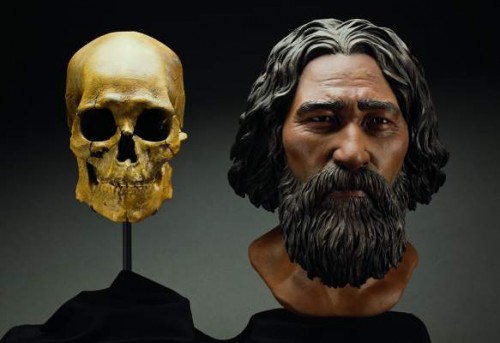

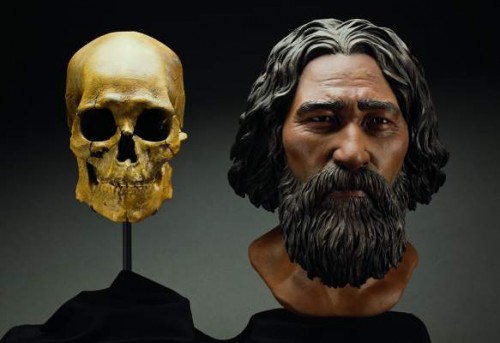

Bothell archaeologist James Chatters, the first scientist to examine the skeleton, said the skull looked “Caucasoid,” not Native American. A facial reconstruction that bore a striking resemblance to Capt. Jean-Luc Picard (actor Patrick Stewart) of the television series “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” further inflamed members of local tribes, who argued that the remains were rightfully theirs under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

After eight years of litigation, a federal appeals court ruled in 2004 that Kennewick Man’s extreme age made it impossible to establish a clear link to any existing Northwest tribes.

A scientific team led by Douglas Owsley, a physical anthropologist at the Smithsonian Institution, won the right to study the skeleton, which is stored at the University of Washington’s Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture.

The results, including a new facial reconstruction based on more thorough analysis of the skull, were published last year in a 669-page book. Owsley, the lead author, told Northwest tribal members in 2012 that he remains convinced Kennewick Man was not Native American.

In an interview last week, Owsley explained that he bases that conclusion on the shape of the skull, which doesn’t look anything like the skulls of modern Native Americans. Its narrow brain case and prominent forehead more closely resemble Japan’s earliest inhabitants and people whose genetic roots are in Southeast Asia, not Siberia and other parts of Northeast Asia.

“His origins are going to go back to coastal Asia,” Owsley said.

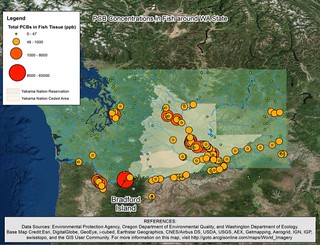

That wouldn’t preclude the possibility of some distant, shared ancestry with Native Americans, he added. But chemical analysis of the bones suggests Kennewick Man ate a lot of marine mammals, which means he probably spent most of his life along the coast of Alaska or British Columbia, not on the Columbia Plateau where his bones were discovered, Owsley said.

With its ability to settle questions about lineage, DNA analysis has become one of the most powerful tools for the study of the ancient world, said Peter Lape, curator of archaeology at the Burke Museum.

“This is yet another case where genetics are really revolutionizing the way we think about ancestry and calling into question older scientific methods that rely on looking at the shape of bones,” he said.

Nevertheless, the majority of visitors he encounters at the museum still have the impression that Kennewick Man is caucasian.

“That initial media storm from 1996 just kind of stuck,” Lape said.

Chatters, the man who kicked up that storm, changed his mind after studying the 13,000-year-old skeleton of a young girl discovered in an underwater cave in Mexico. As with Kennewick Man and other remains of the earliest prehistoric Americans, the shape of the girl’s skull was unusual. But DNA analysis proved that she shared a common ancestry with modern Native Americans, originating with the people who migrated into the land mass called Beringia beginning about 15,000 years ago.

“The result from Kennewick is the same one we’re getting from the other early individuals,” Chatters said. “It’s what I expected.”

Attempts to extract DNA from Kennewick Man’s bones in the late 1990s failed. But the technology has advanced so much since then that researchers recently succeeded in analyzing the genome of a 130,000-year-old Neanderthal from a single toe bone.

Willerslev’s Danish lab is a world leader in ancient DNA analysis. Last year, he and his colleagues reported the genome of the so-called Anzick boy, an infant buried 12,600 years ago in Montana. He, too, was a direct ancestor of modern Native Americans and a descendant of people from Beringia.

Until details of the Kennewick analysis are published, there’s no way to know what other relationships his genes will reveal, Kemp said. It may never be possible to link him to specific tribes, partly because so few Native Americans in the United States have had their genomes sequenced for comparison.

“My feeling is once you get the Kennewick genome, there are going to be people lining up to find out if they’re related to him,” he said.

Members of Northwest tribes visit the Burke Museum regularly to pay their respects to The Ancient One, and continue to press for his reburial.

Willerslev met with tribal representatives in Montana before analyzing the Anzick boy’s DNA. Last summer, after those studies were done, he joined tribal members — including several Northwest veterans of the Kennewick Man wars — as they reinterred the boy’s bones on a sagebrush-covered slope near the spot where he was discovered.